Why Malcolm X’s Critique on Colonial Africa Matters Today

On 11 February 1965, Malcolm X gave a speech to LSE only 10 days before his assassination. Linking the experiences of Black people in the United States fighting for civil rights to Black Africans on the continent fighting for independence, his critiques of liberal economic practices, and the discourses that upheld them, remain relevant today.

Thursday 19 May 2022 marks what would have been Malcolm X’s 97th Birthday. Many people know him as an American civil rights activist and compare him to Martin Luther King Jr. – evoking a false dichotomy to distinguish between acceptable forms of resistance (non-violence) with forms that are unacceptable (violence). This narrow discussion places both men who were brilliant, complex thinkers and orators in simplified and legible boxes, where their contribution is stripped of real meaning. Simultaneously, these figures are publicly valorised in ways that further propagate state control over Black people by crafting narratives that erase both men’s critiques of imperialism, militarism, economic policies and continued racialised dispossession following integration.

But what is often missed is Malcolm X’s ardent critique of colonial Africa and the imperialist forces that condemned Black Africans through liberal economic practices. It is not often discussed how he spread this message with an extensive amount of travel and talks done in multiple African countries such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Nigeria, Ghana, Guinea, Sudan, Senegal, Liberia, Algeria and Morocco from 1959 until his assassination in 1965.

Why does this matter? As we witness an ongoing war in Ethiopia, increased “states of exception” and authoritarian rule connected to the COVID-19 pandemic, the mass flooding of misinformation in state media, and ongoing dispossession and land grabs supported by development banks and multinationals, it is useful to consider how Malcolm X’s critiques remain relevant to a collective Black and African experience.

On 11 February 1965, Malcolm X gave a speech at LSE, only 10 days before his assassination. In this speech his economic critique and challenges to imperialism are made on a global scale, alongside the potential for collaborations to resist these dominating and violent forces. Two critiques in 2022 remain just as relevant.

Critique 1: Both racial violence against Black Americans and imperial violence against Black Africans are upheld by controlling discourses.

Malcolm X begins his speech by reshaping the narrative around the Harlem Race Riots of 1964, which spread to cities across America in response to a veteran police officer killing James Powell, a 15-year-old Black boy – a narrative that sounds eerily familiar in 2022. He legitimises these “riots” as rational resistance to civil rights violations and police brutality, while demonstrating how the economic dispossession of Black people in America and the politics of land ownership influences decisions to break store windows.

The speech turns unexpectedly to connect this environment with US imperial involvement in the Congo. In speaking about the US, Malcolm states:

“They use the press to set up this police state, and they use the press to make the white public accept whatever they do to the dark-skinned public … They have all kinds of negative characteristics that they project to make the white public draw back, or to make the white public be apathetic when police-state-like methods are used in these areas to suppress the people’s honest and just struggle against discrimination and other forms of segregation.” – Malcolm X, LSE, 1965

Malcolm views a connection between the imagery and discourse used to discipline and control Black people in America and that used to legitimise the support of the election of Moise Kapenda Tshombe, the leader of the Katanga people who executed President Patrice Lumumba as Belgian officials watched. The American government provided funds and military support to Tshombe while propagating narratives that his leadership was the only one that could move forward governance in the DRC.

“Because all the press had to do was use that shrewd propaganda word that these villages were in ‘rebel-held’ territory. ‘Rebel-held’ what does that mean? That’s an enemy, so anything that they do to those people is all right.” – Malcolm X, LSE, 1965

The discussion raises the question of how discourses currently used during states of emergency across Africa today legitimise increased authoritarian control, and how they might serve the interests of the global North.

An example can be seen in Ethiopia, where narratives of Tigrayan “rebels” were used to justify a state of emergency in the beginning of the conflict, until these rebels threatened to reach Addis Ababa, the urban hub housing the African Union and a key location for various multinational businesses and multilateral organisations heavily funded by Western governments. The ongoing suppression of alternative media that challenged national media led to incomplete accounts of the conflict. There is little Western intervention in the conflict as business leaders continue neoliberal economic practices in the region without being seen as connected to the political turmoil, immense death and displacement. It is only recently, over a year and a half into the fighting, that the UN warned that the Ethiopian War is reminiscent of conditions found in the Rwandan genocide.

Critique 2: “Peace” and humanitarian initiatives both in the US and Africa are connected to property, land and extractive economic practices.

In the era of Cold War politics and African independence movements, Malcolm X in the same speech at LSE discusses the “ghettos” of America and mineral extraction in the Congo. In relation to the American context, Malcolm X argued that all property in Black communities was owned by White people and White institutions that economically controlled the Black community and disenfranchised them with extractive economic and political practices, which would lead to resistance. While these uprisings were controlled by police and state violence initially, Malcolm X discusses how a shift occurred using “philanthropic imperialism” that crafted narratives of progress with tokenisation that ultimately upheld the status quo of segregation, racism and economic disenfranchisement.

At the same time, he references African independence movements and acknowledges how both Black Americans and Africans could no longer be controlled by fear alone. This led to creations of humanitarian initiatives like the Peace Corps created in 1961, sending their first batch of corps members to West Africa in the height of the Cold War and only a few years after the discovery of oil. In his opinion, philanthropy took the place of colonialism.

In looking at the response to COVID-19 in Africa today, we can see how a global humanitarian discourse for addressing the health concerns of African peoples has also led to further debt pressure, shifting the economic control of African countries to the whims of neoliberal regimes that prescribe specific sets of social action. Today we can see how these actions, though they served the interests and reputations of multilateral institutions, also contributed to increased disregard for human rights in some African countries.

Malcolm X and the potentials for Black and African collaboration

As an activist, orator and leader, Malcolm X grew into his position and opinions through continued study and self-reflection. He was aware of the connection between the systems of economic subordination and violence committed against Black Americans and Black Africans. His insights are relevant to the functioning of the contemporary global economic system. Looking at the discourses that justify authoritative practices, and the ongoing neoliberal extractive economic practices of the West, we can still see reasons why Black people around the world have a stake in a common fight against racial capitalism and the discourses that support it.

Though some may say that Malcolm X’s speech to LSE in 1965 is inflammatory or pessimistic, similar to critiques on Black intellectuals today, I choose to read his tone as urgent and aspirational for continuing to build collective action and coalitions between and among Black people in the West and Black Africans on the continent.

The insights from this blog post were generated by the author in conversation with a study group connected to the virtual Symposia Reimagining Education Work for Collective Freedom organised by faculty at the University of Pittsburgh.

Ikenna Acholonu is currently studying at LSE towards his MSc in Anthropology and Development with a focus on African Development. He also is the Programme Manager for the Uggla Family Scholars Programme at LSE, working to provide access for both home and international undergraduate students that are underrepresented within the institution. This first appeared on Africa@LSE.

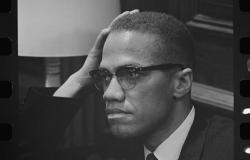

Photo: Malcolm X, 1964. Credit: U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsc-01274. Public domain.

=