Trust in the EU? The Key Obstacle to Reform

The challenges that Europe faces both from within and from outside require immediate, concerted counter-efforts. While efforts to advance the European economic architecture are desirable and useful, can Europe realistically attempt to integrate further on the basis of such little trust?

Current efforts to reform and advance European integration are stalled by a ‘lack of trust’. And while the issue of trust is not necessarily seen and understood in the same way by all, I believe that this deficit in trust in Europe refers to (at least) two specific issues: lack of trust between countries, and countries’ lack of trust in European institutions.

European countries divide themselves in camps along different fault lines: north vs south, east vs west, ins vs outs and – always – them vs us. Some are seen as corrupt and unreliable. Some then feel as part of an OrwellianUnion, “where we are all equal, but some are more equal than others.” What is the source of this suspicion and why does it arise?

Equally, Brussels, the collective term for all European institutions, has become synonymous with elitist, inefficient and distant. The owners of these institutions – in other words, the countries of the European Union collectively – are becoming suspicious of how Brussels serves them, or of what it stands for. This suspicion has made Brussels the source of much that goes wrong in countries domestically, at times a very convenient scapegoat.

Can Europe realistically attempt to integrate further on the basis of such little trust? Even if one imagined that the single market could continue to operate, can we sustain a common currency in the absence of trust when trust is the very basis on which currencies operate?

I believe this to be the one obstacle to the necessary reforms needed to ensure the viability of monetary union and the EU. And yet, the challenges that Europe faces both from within – indebtedness, unemployment, populism – and from the outside – security, migration, threat to multilateralism – require immediate, concerted actions. So, while efforts to advance the European architecture are desirable and useful, it is with the utmost urgency that we need to take concrete steps to improve trust.

There are no quick fixes. The only way to rebuild trust is to earn it. Here are three thoughts on a roadmap that would help advance trust, in order of importance.

1) Set clear annual targets for improving the quality of institutional governance

The deep distrust between countries arises in my view because the quality of domestic governance is simply too diverse. The EU recognises the importance of good-quality institutions. However, from its very genesis in 1957, the circle of members has included countries that were actually very different in this respect. And every time this circle expanded to include new members, it came with the hope of helping the laggards to reform. Institutional reform, and therefore convergence in governance standards, was thought to be easier once inside the circle.

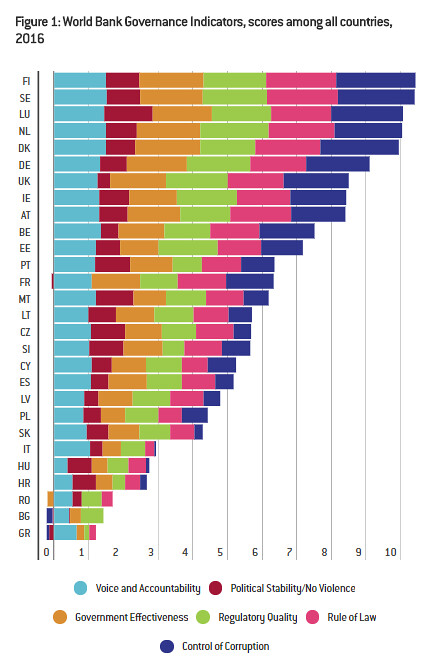

Figure 1, however, shows that this hope, this promise of more effective reform from within, has proven false; the EU has failed to promote convergence in governance. Some may even say that progress is regressing, eroding trust and the willingness to work together, and by implication Europe’s standing in the world.

Source: Bruegel calculations based on World Bank 2016 Governance Indicators

Note: Each indicator can take the values [-2.5, 2.5]. Cumulatively these amount to a range of values [-15,15], with positive numbers being better.

Contrary to governance convergence, when it comes to economic convergence the EU and euro area have explicit monitoring mechanisms in place. But while desirable and useful, economic convergence is secondary to convergence in the quality of institutions, particularly if we are interested in the EU existing in the long haul. And this is because the quality of institutions constitutes not only the basis on which good economic outcomes can arise but also, importantly, be sustained. Good economic performance, while possible in different institutional structures, is likely to be reversed in the absence of good regulations or an effective rule of law.

Yet, we have elaborate economic surveillance processes in place, like the fiscal compact and the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP), to monitor and help reform our economies. We have nothing equivalent for monitoring institutional quality at the EU level. For as long as there is quite such variation in the quality of governance, it will be difficult for countries to trust each other.

At the very least, therefore, we need to put in place a Governance Performance Monitor (GovPM), which will benchmark, monitor and promote convergence to established frontiers. The EU should establish indicators that can evaluate development in the main governance areas at the same frequency as the MIP. This is necessary in order to increase and sustain momentum and to be part of the broad surveillance process to raise awareness and encourage ownership. The tools used to enforce economic discipline and cooperation need to be used also with regards to institutional reform. If governance can be demonstrably improved, economic outcomes will improve and trust will follow.

2) Adopt a systemic approach to policy making

This lack of trust between countries has also led to a split in views, across one more fault line, on how to promote further (and necessary) integration: that between risk sharing and risk reduction. Discussions on how to advance European integration are often divided between either taking action to reduce risk at the country level, or pulling resources centrally to share risk between countries.

But this is indeed a false dichotomy, as this approach to policy-making gives scant attention to the system and its ability to withstand the shocks that hit it. Given the degree of our interdependence, it is important to approach Europe as more than just the sum of its parts and any attempt to further integrate should be driven by a desire to strengthen the system. Strengthening systems, in turn, requires both reforming their parts (risk reduction), as well putting mechanisms in place to hold these parts together as a system (risk-sharing between countries and with the markets).

This is not unlike a nation’s health policy: we promote healthier lifestyles as a way of strengthening each part of the system (the individual), but we also enforce collective insurance so that the health system as a whole survives. Left to themselves, health insurance schemes would not survive, as only the unhealthy would seek to subscribe. The collective nature of agreements, effectively forcing the healthy to also subscribe, helps resolve this and recognises that the current healthy may also be its future consumers. This is what economists call resolving the problem of adverse selection. At the same time, and equally crucial to the viability of the system, is making sure that the premia paid reflect lifestyles. This in turns resolves the problem of moral hazard.

A systemic approach to further integration in Europe requires actions at both levels: targeted structural reforms at the country level to modernise and adapt economies, as well as to coordinate policies and install buffers at the European level. And they need to be done simultaneously, not sequentially.

Any attempt at risk-sharing between countries is dangerous, if at the same time countries individually do not pursue “healthier lifestyles”: improve governance, promote productivity, encourage equitable distribution of wealth created. One cannot ask the healthy to guarantee the health of the weak. The system should do that because it has an incentive (namely a threat to its existence) to promote, if not enforce, reforms.

Similarly, the insistence on “country reform” before anything else happens, ignores the relevance of insurance in closely interconnected systems. A common currency, one banking union, one single market, are all at risk if appropriate mechanisms of monitoring (ex ante) and rescuing(ex post) are not put in place. Economic and governance monitoring, and designing ways of reducing the way the health of sovereigns can affect banks, are examples of how to achieve the former. Completing banking union and installing a system for allowing countries to have manageable and orderly defaults are examples of how one might insure the system.

But importantly, efforts at both levels simultaneously demonstrate that all countries have the same objective, which is to protect the system. And this demonstrable alignment of interests would set the path for re-establishing trust.

3) Aim to close the distance between Brussels and the national capitals

This is crucial for restoring countries’ trust in European institutions. If Brussels is indeed elitist, inefficient and distant, the owners of European institutions, the countries, should put in place motions to correct that. There is always space to modernise and become more efficient and European administration is no different.

But this will not be enough. A recent Eurobarometer run by the European Commission on the European Budget reported that “Respondents are most likely to think the EU spends most of its budget (on) administrative and personnel costs and buildings (34%), defence and security (27%) and immigration issues (27%).” This is very different to what the budget is actually spent on, with the common agricultural policy and structural funds capturing about 80% of the total, and personnel costs and buildings capturing way below 10%. The very startling misperceptions that citizens have on what the European budget does are indicative of how little effort is made to inform them.

In the long run, there cannot be such a severe disconnect between what the EU does and what people believe it does, without threatening its very existence. And here it is the countries that need to take the lead and explain to their own citizens why they are in the EU, how they benefit from it and what they contribute to its success. A domestic dialogue on Europe with historical contextualisation – what it does well and what it needs to do better – will eliminate the misperception that Brussels is here to serve anyone or anything else, other than all Europeans.

But beyond communication, the only way this distance can close is if the benefits of membership are seen and felt. It is crucial to meet citizens’ concerns and adapt as these concerns change. A concrete example would be the new seven-year EU budget (MFF), the negotiations for which are about to begin. The motivation in allocating funds needs to be what makes the EU more robust. Defence and security, investing in education, technology and the young, and the convergence of institutions and economies are items that will affect all and should take centre stage in this process of negotiation. Letting go of the juste de retour straightjacket is crucial for approaching the EU as a system, not just a collection of countries that can meet future adversities.

If the EU wants to prepare for the uncertainties of the future and all the challenges that it will bring, sustainability needs to be at the core of its objectives. Trust is at the basis of everything that makes our societies successful. If that is gone, it is difficult to build and sustain the architecture required. Restoring trust between countries can only begin if all of them take actions to ensure that the EU, as more than just the sum of its parts, can survive in the long run. Similarly, countries have a responsibility to ensure that the institutions that are there to serve and promote the EU are seen and trusted to do so. The process of restoring it cannot start soon enough.

Maria Demertzis is Deputy Director at Bruegel. She has previously worked at the European Commission and the research department of the Dutch Central Bank. She has also held academic positions at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government in the USA and the University of Strathclyde in the UK, from where she holds a PhD in economics. She has published extensively in international academic journals and contributed regular policy inputs to both the European Commission's and the Dutch Central Bank's policy outlets.

This post first appeared on:

Image credit: purplejavatroll via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)