Is Democracy the Political Ideology that Will Divide the World Next?

Dharish David and Louis Martin-Vezian explore the possible ramifications of Biden’s Summit for Democracy.

While the economic damage from the pandemic has been extensively covered by global media, the erosion of democratic institutions and the subsequent emboldening of authoritarianism in the backdrop of temporary COVID restrictions deserves another look. Democracy was never a political ideology that was pushed outrightly as a system that should be pursued by all countries, but it was an implicit goal for Western countries to promote it across the world. The Summit for Democracy was conceived by President Biden in 2020, the year before the Democrats came back to power in the White House. It was held a year later in December 2021 and will be an ongoing effort to ‘defend, sustain and strengthen democracy around the world’. Of the 110 countries that were invited 108 attended, while 98 were part of statements issued over the course of the summit. Apart from state actors, the summit featured appearances from activists, including Hong Kong Activist Nathan Law, leader in exile Juan Guaido, dozens of labour groups, Non-Government Organisations (NGOs), and advocacy groups.

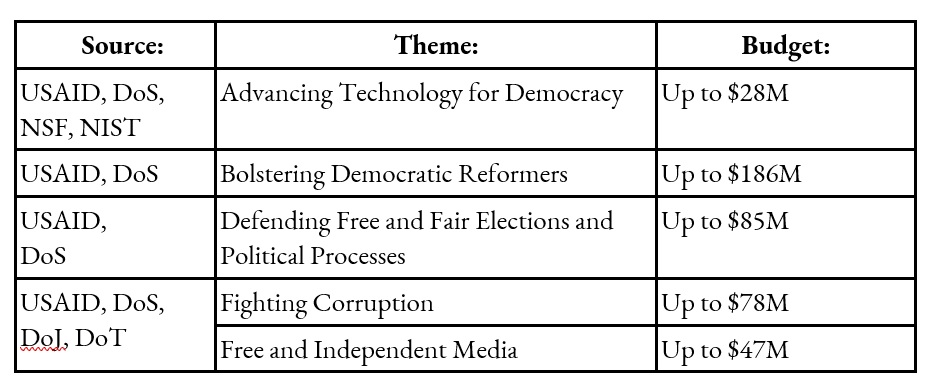

The opening remarks were delivered by President Biden and Secretary of State Blinken, highlighting the need for democratic champions in the face of 15 years of democratic stepback, citing Freedom House data. The American president emphasised the need for a democratic renewal to bolster eroding democratic norms in the face of autocratic leaders expanding their influence, and announced a half billion dollar (refer to the table below) funding to support a series of newly formed and existing programs. This American effort to put a spotlight on ‘democracy’ as a much needed systemic solution to today’s complex world raises the question of whether a new criteria is emerging to split the world again based on political ideology. The question is whether it is an effort to genuinely engage countries to develop institutions and inclusive political decision making processes or was it was put together hastily to challenge non-democratic authoritarian super-powers and strongmen in China and Russia? Incidentally, these two countries also have the longest lineage as autocracies.

America’s Announced Funding for the Democratic Renewal Programs

Source: “Fact Sheet Announcing the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal,” The White House, December 9, 2021

The summit for democracy last year was promoted as a series of democratic promotion initiatives originating from the US since the early 2000’s. Among them the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue - a security partnership of the 4 largest democracies in Asia. Such initiatives had only limited success at the time of their inception as succeeding U.S. Administrations focused their bandwidth on the Middle East and Europe. The promotion of democracy in particular was seen as an unweildly civilizational endeavour by the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan, while the promotion of human rights was often discarded as a mere attempt at justification. Additionally, U.S. policy was still committed to the strategy of ‘engagement’ with China. Twenty years later however, the decay of international institutions and the end of American uncontested military dominance are ushering a new era of multipolarity, and along with it, increased room for competition.

For the United States, The Summit for Democracy fits with the ‘open world’ Grand strategy developed and advocated by Rebecca Lissner and Mira Rapp-Hooper. Written in 2018, the book envisioned the policies needed to restore U.S. credibility after the Trump years, and layed out a compromising grand strategy to shape the 21st century. Centred on governance, technology and open trade, this new competition is embedded into high levels of interdependence worldwide. For this, the book advocates for the U.S. to compete with Chinese influence on finance, trade and technology, in a non-polarising way to promote openness. Part of President Biden’s campaign, the Summit for Democracies initially included three main thrusts, namely 1. fighting corruption 2. defending against authoritarianism including election security and 3. advancing human rights’. Those items were subsequently supplemented with three further focuses: 1. Supporting a free and independent media, 2. Advancing technology for democracy and 3. bolstering democratic reformers.

The inclusion or non-inclusion of states seem to have been mostly the result of competing global or regional focuses within the U.S. Government's various departments, but also with partners and allies. In the case of the Indo-Pacific, which by all accounts is the policy focus of the Biden Administration, the omission of Singapore and Vietnam are glaring examples of a diplomatically counter-productive move. Vietnam recently reopened its port of Da Nang to U.S. supercarriers while Singapore is one of the bigger purchasers of U.S. weapon systems.

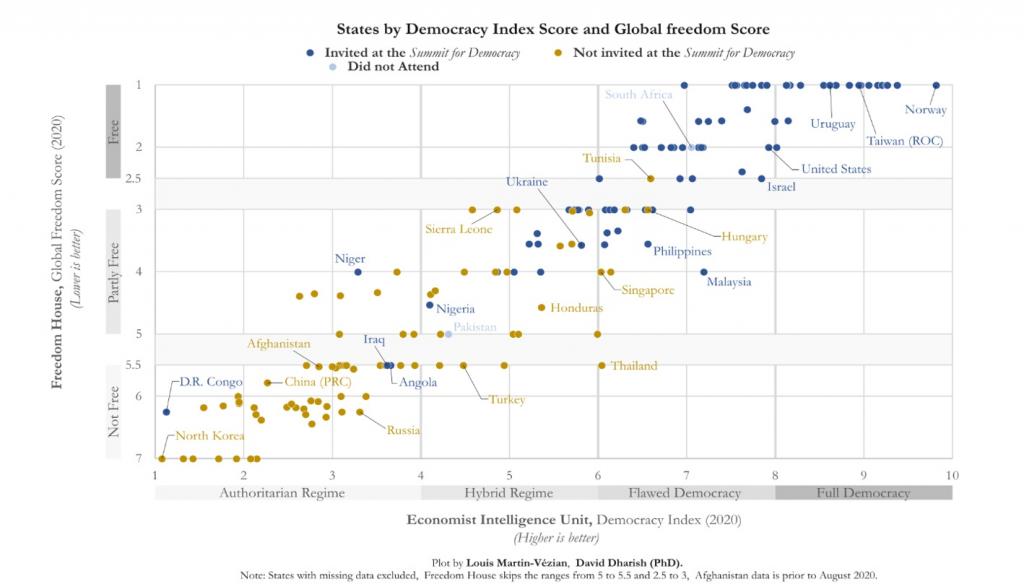

While the summit for democracy gives the impression of exclusivity to a small club of democratic nations, the participant list instead highlights a wide selection, with some states scoring relatively low in both the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index, and Freedom’s House’s (FH) Global Freedom Score. Those indexes combine different metrics to score the level of democratic health, and the range of freedoms in states, the EIU index ranges from 0 to 4 for authoritarian regimes, 4 to 6 for hybrid regimes, and 6 to to 10 for democracies, flawed or full. The FH freedom score goes from 7 to 1, with 7 being the least free, and 1 being free. Interestingly, several invited states scored well below the ‘Authoritarian’ threshold in the EIU 2020 index, while some scored as low as 1.13 (the U.S. scored 7.92, in the Flawed democracy range). Two of the lowest scoring states that were nevertheless invited are Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In both cases newly elected leaders are battling the power base of former strongmen, distributed in the administration, financial institutions and the army. While attempting to build or strengthen their support base, those new leaders have had to wield anti-corruption policies with care. In the case of Angola, the incumbent authoritarian leader Jose Eduardo dos Santos did not present himself to the 2017 elections. His successor, João Lourenço, (formerly Minister of Defence from 2014 to 2017 and Secretary General of the MPLA between 1998 and 2003), initiated an anti-corruption drive amid the ‘Luanda Leaks’ that eventually condemned two of dos Santos’s children.

On the other hand, some of the states not invited scored above the ‘Flawed Democracy’ mark. Singapore with a EIU index score of 6.03 and a ranking of 4 in the FH freedom index, classifies as a Hybrid regime, with a ‘Partly Free’ civic society. Singapore has an impeccable anti-corruption track record however, and with the summit held on the world’s anti-corruption day, its inclusion wouldn't have seemed out of place. Domestic commentary in Singapore. In Europe, Hungary was not invited either despite a relatively high score. This was seen as being snubbed by Budapest, and in return it blocked the European Union from being able to attend as a formal member.

Despite the apparent aspirational goals of the Summit given its rather inclusive guest list, the framing of the ‘Summit for Democracies’ and its exclusion of the traditional adversaries of the United States raise the question of a coming ideological struggle for the 21st century. The brutal and unprompted Russian attack against Ukraine and its subsequent ostracization in the United Nations highlighted the split between ‘democracies’ and authoritarian regimes. Three quarters of the Abstentions and votes against UN Resolution ES-11/1 condemning Russia’s ‘Special Operation’ in Ukraine were among the states not invited to the Summit, while only 9 invited states abstained. The conflict also highlighted the rather close relationship between Russia and China whose’ state media routinely replicates Russian talking points and justifications for the invasion.

Immediately following the summit’s announcement, the Russian and Chinese ambassadors to the United States published an op-ed decrying the summit for its exclusive nature before laying out an argument explaining that both China and Russia were actually successful democracies. Bringing it a step further, China was quick to organise its own ‘Democracy forum’ a week ahead of when the American summit was to take place. Chinese vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng delivered a speech boasting China’s “Whole-Process Democracy”, other speakers included Singapore’s former Foreign Minister Kishore Mahbubani. A 30 page report laying out the argumentation for the whole-process democracy was subsequently published by China’s Propaganda Department. The two conferences had in common only a title, highlighting the convoluted nature of 21st century global competition, whereby both camps appear to claim ownership over the same form of political ideology and are instead competing on governance.

Towards a politically ideologically divided world?

The summit for democracy is attempting to counter growing authoritarianism worldwide by proposing a new approach to multilateralism, from the end of the unipolar world to the rise of alternatives to the various institutions making up American ‘soft hegemony’. For this the Biden administration attempted to kickstart a democratic renewal by combining a set of policy objectives loosely based on democratic reforms, to delay the erosion of the current open global system. Yet by attempting to rally like-minded nations through an ideologically laden summit, the U.S. could be increasing the incentives for adversaries like China and Russia to increase their search for an alternative global system as they consider the promotion of democracy to be a challenge to their own rule. On the other hand the US and its democratic allies are using tried and tested interest-based incentives through the bilateral meetings in the Indo-Pacific, and elevating the core values including democracy and human rights that underpin the US-Taiwan relations that is also currently raising tensions.

Dharish David (PhD) is an associate faculty for the University of London at the Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE), teaching courses relating to political economy. He has written widely on infrastructure development, Asian political economy, economic development, and international relations. He can be reached at david014@mymail.sim.edu.sg and twitter handle: @dharishd.

Louis Martin-Vézian is a Master candidate at the Johns Hopkins' School for Advanced International Studies, Washington D.C. with an interest in International Relations and the Indo-Pacific. He has a BSc in Economics and Politics at the University of London/Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE). Louis is the founder of CIGeography, where he publishes maps and analysis. He can be reached at CIGeography@gmail.com and twitter handle @LouisMVezian / @CIGeography.

Image: Camille King via Flickr