Want to tackle inequality? Start with fair taxes and giving the Global South a real voice at the IMF and World Bank

Global inequality will continue to spiral in a skewed system of international finance and governance that heavily favours the Global North, says Anthony Kamande in the latest blog in our Davos series.

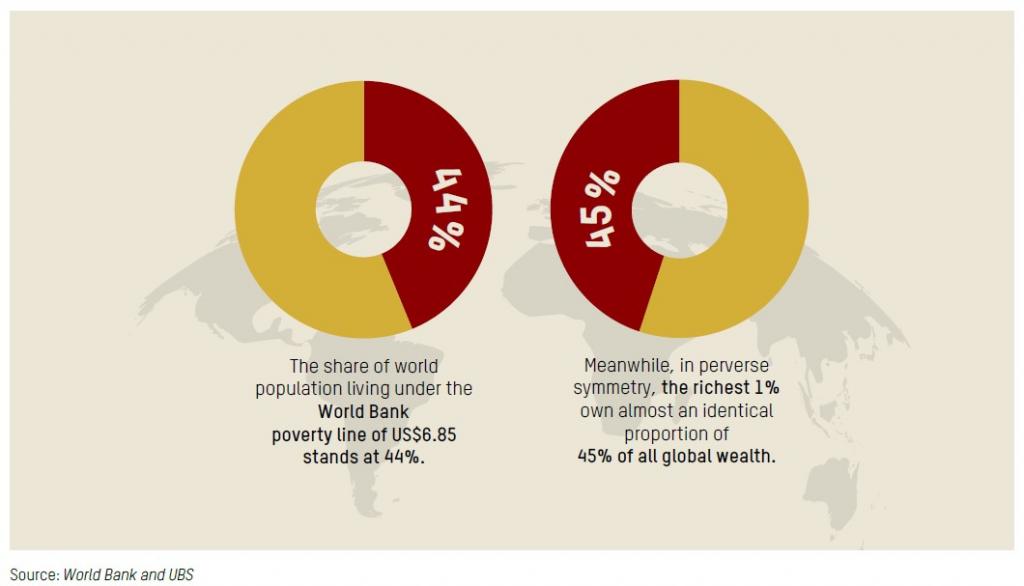

Progress to end global poverty has stalled. At the current rate, it will take more than a century to end poverty (at $6.85 a day), according to the World Bank.

The greatest harm is to poor people in poor countries. More than half of low- and middle-income countries are spending one in three dollars of their tax revenue on repaying debts. This leaves little for health, education, and other critical public services. Small wonder that, in Pakistan, the chance of a student from the poorest 20% of society completing secondary education is 1%; whereas in Canada, every child completes secondary school.

In rich countries too, ordinary people are suffering. In the US, homelessness hit a record high in 2023, with racialised and marginalised communities impacted the most. In the UK, the use of food banks is at a historic high as incomes fail to keep up with the rising cost of living.

A growing concentration of wealth driving inequality and damaging our planet

Clearly the poorest are not benefiting from the trillions flowing around the world in global trade and markets. So who is? Our new Davos report shows it is the world’s richest 1% and the billionaires.

The world’s billionaires, who number fewer than 2800, are richer than they have ever been. Between them, they now have a combined net wealth of more than $15 trillion. If these billionaires were a country, it would be the third richest country in the world, just behind the US and China.

2024 was an especially good year for the world’s mega-rich. A new billionaire was minted every week on average between 2023 and 2024. The billionaires made more than $2 trillion in new wealth in 2024, almost equivalent to the entire GDP of Canada, the world’s 9th biggest.

Extreme wealth is not just denying dignity and better lives for billions of people but it is also damaging our planet. The richest 1% are emitting more greenhouse gases than two thirds of the humanity; within the first 10 days of 2025, they had already emitted their share for the whole of 2025. Extreme weather events due to climate change are severely hitting people least able to cope. With 2024 being the hottest year on record, things will only worsen. The world’s richest people will be hardly affected.

Extreme wealth is not because of meritocracy

It is not even that this increasing wealth of the richest few and the suffering of many is because the rich are necessarily more talented or entrepreneurial. Indeed, our new Oxfam Davos report reveals that about 60% of billionaires’ wealth is from cronyism, corruption, abuse of monopoly power and inheritance.

Lack of opportunities, including quality education, discrimination based on race and gender, the family where one is born, and the country of birth are a significant barrier to the success of many and reducing inequality. We cannot speak of meritocracy when a poor child misses an education because of out-of-pocket costs, while their neighbour goes all the way because the family has the means to send them to the best schools. These two children will be very different in their lifetime. I can think of so many students I knew at my primary school who had to drop out because their families could not afford for them to continue.

A colonial legacy leaves the Global South without a fair voice in global institutions

A key argument in the report is how wealth is built on the legacy of colonialism and all the systems, norms and structures developed from that era. That includes international institutions and an international financial system that is controlled by and heavily favours rich countries.

The World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) were created 80 years ago, near the end of the historical colonial period, and their unequal governance has changed little since then. G7 countries (a group of seven richest Western countries, including Japan) still hold 41% of the votes in the IMF and World Bank despite having less than 10% of the world’s population. The average Belgian has 180 times more voting rights at the International Bank of Reconstruction and Development – the main arm of the World Bank – than me as a Kenyan citizen.

The leaders of the World Bank and IMF are still decided by the USA and Europe respectively. This matters because they remain hugely influential in shaping the global economic system and, in particular, the economic policies of low- and lower-middle income countries

Such power imbalances lie behind a skewed financial system which means that, while formal colonialism ended decades ago, extraction and domination has not. And the main beneficiaries of this exploitation are the richest people in rich countries and a handful of rich people in poor countries. Our Davos report reveals that, in 2023, countries from the Global South transferred $30 million per hour to the richest 1% in the Global North. This kind of outflow leaves poor countries with no money to spend on kids’ education.

Time to tax the wealthy and change the balance of global financial power

Reducing inequality is within reach of every country, no matter their level of development, and history has shown how this can be done. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel. How can we do this?

The first thing is to ensure that the richest pay their fair share of taxes to radically reduce inequality and end the re-emergence of a new aristocracy. For most of the world, taxes on the richest have been on the decline, while low-income earners, the working class, and the poor have been shouldering most of the tax burden. We need radical measures to address this worrying trend: for instance, capital gains and corporate income taxes should be at the same rate or higher than taxes on salaries and wages. We also need wealth taxes such as on inheritance and unrealised capital gains to prevent the re-emergence of a new aristocracy.

International tax treaties should be fair to poor countries and not skewed towards multinationals and rich countries. Such international coordination is more necessary than ever to close the profit-shifting and base erosion that is denying poor countries billions of dollars. Ensuring that the wealthiest pay their fair share will increase revenue for social spending and reduce the concentration of economic and political power.

The second thing is to remove the imbalance in the global financial and governance architecture and end the unequal and colonial relations between rich and poor countries. This will involve giving countries from the Global South their rightful voice in global institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank through more voting rights and decision-making. The decisions and policy advice of these institutions should be geared towards empowering countries of the Global South to build more equal countries. In addition, ensuring that trade agreements are not extractive, including on the issues of patent transfer, would spur development where it’s needed the most, lead to healthy competition, and dilute the power of monopolies.

Tackling today’s inequality crisis requires bold action. It calls for the state to play a fuller role and for the international community to safeguard a just and more equal world where everyone has the opportunity, resources and environment they need to thrive and be the best of themselves.

Anthony Kamande is Inequality Policy and Research Advisor at Oxfam International.

This is the third in a series of blogs for Davos 2025. Catch up on all our Davos blogs here and follow us on BlueSky, Twitter/X and LinkedIn for the latest Davos content. And join our campaign to tax the super-rich here.

Read the full report for this year’s Davos summit: Takers Not Makers: The unjust poverty and unearned wealth of colonialism. And you can also read the full methodology note for the report.

This piece has also been posted on Views and Voices and From Poverty to Power. Subscribe to the Equals Substack for more on the Davos report and inequality.

Photo by Polina Tankilevitch