Deadly Interferences: The Regional Proxy War in Yemen

Yemen is suffering one of the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophes. To resolve it, it is necessary to look beyond the national conflict.

Yemen’s civil war is complex. It’s a violent conflict between competing Yemeni factions, each of which is allying itself with regional, sectarian, tribal and Islamist groups. The country has a long history of instability and the roots of the conflict are deep. Before and after the unification of the two former states, the Yemen Arab Republic and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, in 1990, historical grievances have been rarely addressed. Political, economic and social exclusion of whole social groups and regions have been a constant in Yemeni political history. Failure in working together to overcome grievances and national divisions can explain the recurrent wars.

As the forthcoming 2018 Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) report on Yemen summarizes, “The country has two governments now – the Houthi-backed ‘National Salvation Government’ based in the capital Sanaa and the government following internationally recognized President Hadi, based in Saudi Arabia and the ‘temporary capital Aden’. Neither of them has the power to win the war (although both of them employ regular as well as irregular forces), let alone to govern the whole country.”

But this is only the national dimension. The second dimension of the violent conflict is regional: the civil war is taking place against the backdrop of a deepening rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran, one that is destabilizing the whole region. This rivalry is geopolitical in nature, but framed by sectarian and ethnic differences: Sunni Arab versus Shiite Persian. Each actor in the region is supporting different sides of the political, sectarian and regional conflict. A regional proxy war is taking place, and its prime battleground is Yemen, taking enormous tolls on the population.

The enmity between Saudi Arabia and Iran

The history of the Saudi-Iranian rivalry is old, too. The schism between Sunnis and Shiites developed from a political dispute over who should become the ruler after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. But the conflict itself is geopolitical to the core: Each country claims to be the leader of the Islamic world, each representing a form of politicized radical reading of Islam, and each is seeking to spread its influence in the Arabian Peninsula.

The rivalry took a qualitative turn after the 1979 Iranian Islamic revolution. Iran attacked the Islamic credentials of Saudi Arabia, and sought to export its revolution and topple the Gulf countries’ regimes. This led to an active Saudi policy, enforcing the dogmas of its version of Sunni politicized fundamentalism in its own borders while spreading it worldwide. Similar to Iran, religion became a Saudi tool to claim leadership of the Islamic world.

The rivalry receded starting from the Gulf War waged by coalition forces led by the United States against Iraq in response to Iraq's annexation of Kuwait in 1990, but soon after the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 it reignited again. Up until that invasion Iraq – a Shiite majority country – had been ruled by an elite Sunni minority hostile to Iran. The policy mistakes of the Bush and Obama administrations opened the path for Iran to expand its influence in Iraq militarily, politically, economically and culturally. Once it secured its position, it used it as a launching pad for a stronger proactive role in the region.

Saudi Arabia saw in Iran’s strengthening role an existential threat, even more because the bulk of Saudi oil fields are located in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia, where a majority of the Shiite minority lives. These people have been resentful of their second-class citizenship status and Riyadh has often looked at its own Shi’i population as a fifth column, a political instrument of Iran. It feared that the empowerment of the Shi’i population in Iraq and Iran’s expanding regional role was bound to affect its own security.

Locations of the proxy war

From then on, wherever the Saudi leadership detected an Iranian role, real or perceived, an active intervention was followed. In Iraq it supported Sunni clans and extremist groups, igniting a bloody civil war. In Bahrain – also a Shiite majority country ruled by an elite Sunni minority – it intervened in 2011 militarily and violently ended a peaceful uprising. In the Syrian civil war, it fuelled the uprising against Bashar al-Assad’s Regime, who is backed by Iran, with its generous supports to Sunni Islamist factions.

Yemen was only the last regional front of the escalating tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran and just another battlefield for the same proxy war. In March 2015, the Yemeni national conflict reached its height. The Houthi militia’s took over half of the country, and from the perspective of the Saudi leadership, a new Iranian zone of influence was on the rise.

Frustrated by the rapprochement of the Obama administration towards Iran in the negotiations on a nuclear deal, which were taking place at the same time in Lausanne, the United States was no longer a trusted ally that could guarantee the Saudi Arabian security. Adding salt to the wound, some Iranian hardliners were publicly bragging about Iran’s march in the region. Starting the proxy war was therefore a miscalculation born out of frustration.

A war without winners

If the Saudi air attacks were meant to stop the Iran nuclear deal, signed in April 2015, the strategy squarely failed. If Saudi leadership thought it could decide the war in favour of its Yemeni allies within a ‘two weeks period’ as the Saudi military spokesman declared at the time, the continuous war has only reinforced a well-known historical lesson: interfering militarily in Yemen tends to be disastrous. If it was meant to end the Iranian role in Yemen, in fact, one could argue that the airstrikes turned a perceived role into an actual one. Unlike the beginning of the war, today Iran is directly involved in the war and actively supporting their Houthi allies.

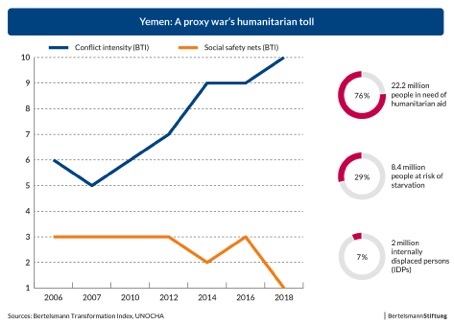

But it needs to be stressed that even without Saudi and Iranian interference, the Yemeni civil war would have happened. The regional dimension only exacerbated the conflict and led one of the poorest countries in the Middle East into the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, ravaged by preventable diseases and on the verge of a historic famine. The outlook of the forthcoming 2018 Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) report on Yemen is therefore sobering: “As long as Saudi Arabia and Iran do not achieve some kind of rapprochement, a peaceful resolution to the conflicts in Yemen is out of sight. Also, Yemen’s complicated political history has repeatedly shown that the main roots of Yemen’s repeated crises – group’s grievances, lack of institutional basis, and irresponsible behavior of the political elites – are hard to tackle.” The combination of the national and regional dimensions of the Yemeni conflict makes sustainable peace without a UN mandate on Yemen extremely unrealistic. Therefore, it is high time to think out of the box.

Elham Manea is Associate Professor for Political Science at the University of Zuerich. She works as a consultant for governmental and international organizations, for instance the World Bank, Freedom House or the United States Agency for International Development. Besides, she is an expert on Yemen in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) network.

Image credit: Gerry & Bonni via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)