Is it Time to Embrace your Imposter Syndrome?

Duncan Green on an issue all too common yet often undiscussed.

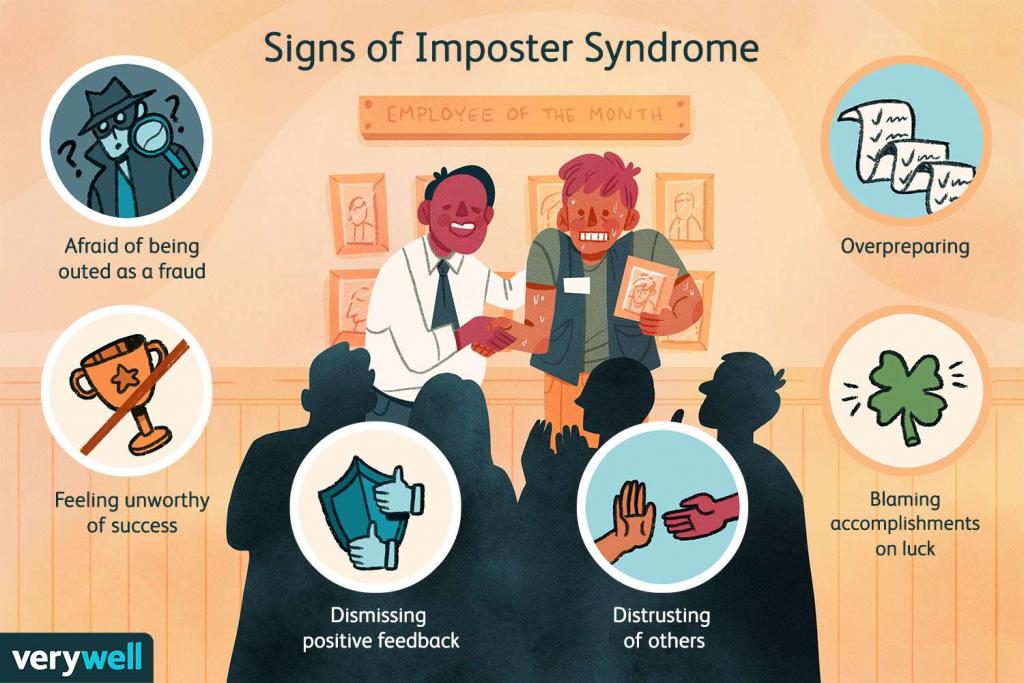

Imposter Syndrome – doubting your abilities and feeling like a fraud. (Almost) everyone has it, even old lags like me. Just because I’ve become relaxed about banging on in front of an audience, doesn’t mean I’ve stopped living in fear of someone pointing at me and saying ‘you don’t really know what you’re talking about, do you?’ Luckily, the only people who actually do that (at least out loud) are my wife and kids – and they are usually right.

My students raise it; so do colleagues, usually with a wry smile of recognition; of a shared malaise.

Why write about it? In heavy doses, it can incapacitate people, draining them of self-belief, blinding them to their own capacities and potential, and preventing them from seizing opportunities to learn, do good things and expand their horizons. It means you devalue/fail to celebrate your achievements through the closely related Groucho Marx syndrome – if you can do it, it can’t be worth much. Curbing imposter syndrome can open the door to a bit more self-awareness, where you realize when you know what you’re talking about and you also know when you’re on thin ice it and are confident enough to let others know and ask them/ yourself whether it’s time to stop or ask for help.

What about late career people like me, reasonably established, with long CVs and at least a veneer of self confidence? There I think allowing yourself to feel like an imposter can actually be healthy. Embrace it, because it reminds you that you don’t know everything. In fact you don’t know very much. If a ‘memento mori’ is a reminder of the inevitability of death, maybe we need a ‘memento impostoris’ (sorry, never did Latin) to remind us of fallibility and error. A form of evidence-based humility. ‘Standing on the shoulders of giants’ could be a form of that, but has always struck me as an early form of Newtonian humble-bragging.

Acknowledging your own insecurities and doubts (along with my old favourite, TSD – tactical self-deprecation) can also be a way of redressing imbalances of power – between expat and national in the aid business, or between prof and student.

Of course, it’s highly gendered: over the years, I’ve noticed that women sometimes email me with a comment on a blog post, saying ‘I didn’t want to post this – not sure I know enough’. Never men. In fact, the syndrome’s origins lie in trying to understand the challenges faced by women leaders, as this 2021 piece in the Harvard Business Review points out.:

‘Psychologists Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes developed the concept, originally termed “imposter phenomenon,” in their 1978 founding study, which focused on high-achieving women. They posited that “despite outstanding academic and professional accomplishments, women who experience the imposter phenomenon persist in believing that they are really not bright and have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise.” Their findings spurred decades of thought leadership, programs, and initiatives to address imposter syndrome in women. Even famous women — from Hollywood superstars such as Charlize Theron and Viola Davis to business leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and even former First Lady Michelle Obama and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor — have confessed to experiencing it.’

The authors of that piece, Ruchika Tulshyan and Jodi-Ann Burey, argue that imposter syndrome is actually structural:

‘imposter syndrome puts the blame on individuals, without accounting for the historical and cultural contexts that are foundational to how it manifests in both women of color and white women. Imposter syndrome directs our view toward fixing women at work instead of fixing the places where women work.’

They see men as shedding the syndrome as they progress in their careers (I’m not so sure), while it continues to hold women back, and they think labelling it may even be counter-productive in individualising what should be a structural discussion.

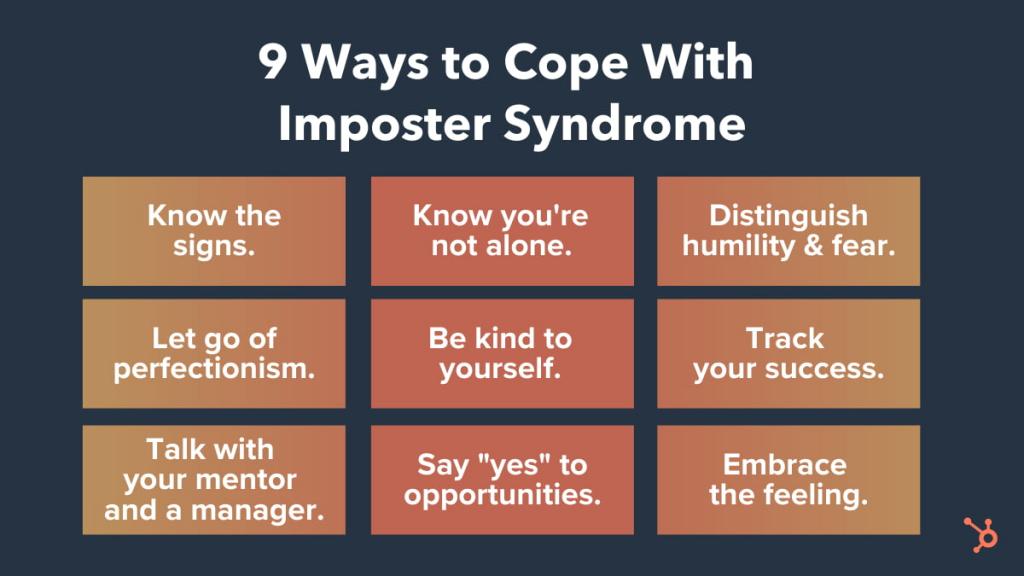

So I guess I’m arguing for just the right level of imposter syndrome, ensuring that you remain open to error, learning new things and appreciating the wisdom of others, without being paralysed by self doubt. A productive tension between doubt and action. That’s a tough balance to strike, but I think it’s the right (and most productive) one.

How to strike that balance? My advice to students – don’t let your doubts grind you down. Trust yourself and your peers. Jump in, the water is (generally) lovely. Feel the fear and do it anyway. Hard to do, but building supportive networks, finding a safe-space to take risks and build confidence, whether in public speaking, writing or whatever, can help. I guess University plays that role for many, even if it’s largely unacknowledged. Teachers need to be part of building that safe space, obviously.

Source: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/impostor-syndrome-tips

To colleagues further on in their careers, imposter syndrome can be an antidote to false certainties. Embrace it (along with uncertainty and ambiguity). If it feels like it is damaging your self-confidence too much, look at those around you, see who shares the syndrome and draw comfort from that. Then of course, you only have to look at colleagues who appear to have shaken off their imposter syndromes altogether to see how quickly that turns into the kind of deaf arrogance that can give veterans, whether in aid or academia, a bad name.

And of course, this may all be a British malaise, except that lots of non-Brit students have told me the same thing. Any other thoughts/advice?

(Thanks to Jane Lonsdale for comments on the draft)

This first appeared on From Poverty to Power.

Photo by Sebastiaan Stam