Can McDonalds tell us anything about the value of the social sciences?

Taking a sideways look at George Ritzer’s famous McDonaldization thesis, Titus Alexander argues that rather than being an iron cage, social scientists have much to gain from treating such institutions as real time experiments and social models.

In his classic work The McDonaldization of Society, George Ritzer argued that the principles used by the fast-food chain dominate many sectors of society, including universities. Ritzer developed Max Weber’s idea that bureaucracy and capitalism trap people in an “iron cage” of rationality in their drive for efficiency, predictability, calculability and control. However, it was an analysis that did not slow the rise of McDonald’s from under 10,000 outlets to over 40,270 in 2023, nor its soaring share price (Fig.1).

However insightful, this critique does not enable people to solve social problems or improve society. If anything, it paralyses them. In this instance making McDonaldization into an unstoppable force they are powerless to influence. In his 2017 work, Beyond McDonaldization: Visions of Higher Education, Dennis Hayes confessed to a similar ‘Weberian pessimism’ about the inevitability of McDonaldizing tendencies in universities and the consequent devaluation of critical thinking and intellectual exploration.

Fig.1. Source: Macrotrends: McDonald’s – 51 Year Stock Price History | MCD. Arrow points to origins of McDonaldization thesis.

However, might a bigger problem be, as William Starbuck observed, hundreds of thousands of talented researchers are producing little of lasting value, because they are focused on producing journal articles rather than knowledge? Social sciences can do better. They offer many methods and findings to improve society. But to benefit from their insights, social scientists need to help people use knowledge better, just as McDonald’s uses knowledge for better or worse to propel its growth.

Like a theory in the natural sciences, McDonald’s has a replicable model of an aspect of reality that enables people to achieve specific outcomes—meals, celebrations, employment, identity, returns on investment, status, etc. This formula ensures consistent outcomes across continents. Just as space travel depends on constant laws of physics, McDonald’s relies on consistency across many socio-political and economic regimes.

Most institutions have more complex aims than McDonald’s, but it illustrates how social research can improve society by treating institutions as social experiments and models of how to achieve specific outcomes. Every institution embodies knowledge about how to do things. People copy or adapt institutions to achieve similar outcomes. A synagogue, school, or street market is recognisable across centuries, countries, and cultures. Institutional models are scaled up, refined, and replicated to provide similar functions in different societies, or adapted to achieve different outcomes. A social model is never static. Yet, some embody behaviours and knowledge for generations, surviving dramatic changes in belief, like the Tsarist state in Putin’s Russia. Social models may therefore be seen as ‘dynamic social theories’, tested and developed in reality every day.

Layers of Social Analysis

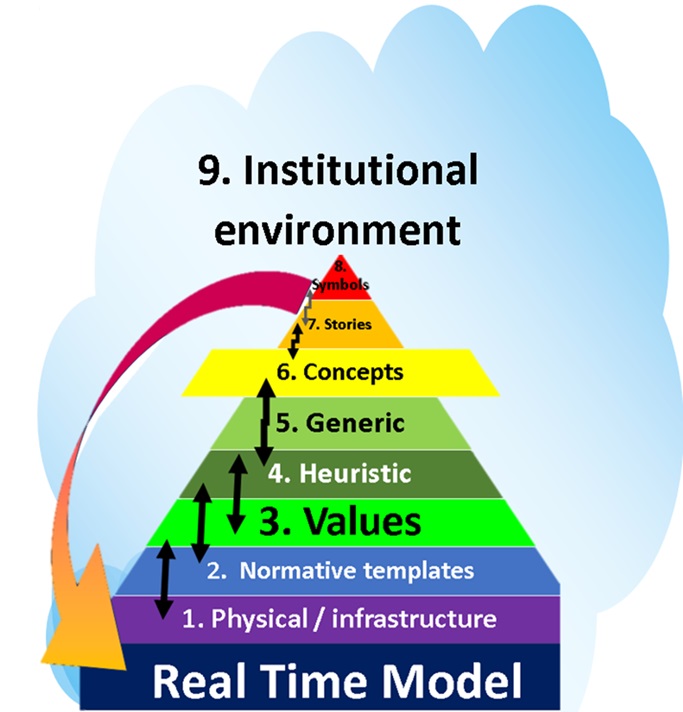

In this respect McDonalds, may provide an unlikely model for applied social science. I argued recently it uses at least nine layers of analysis to bring about its outcomes (Fig. 2). Each McDonald’s outlet is a unique real-time model that includes the experiences, emotions, aspirations and beliefs of people involved, as well as the knowledge, skills, processes, routines, and relationships that make it work. Their performance may be tightly prescribed, but it has built-in processes for review and renewal. Many of its innovations, such as Big Macs, Filet-o-Fish and the McVegan, came from staff and customers far from headquarters.

Fig.2: Layers of analysis in social models blend into and inform each other, since they are all dimensions of the real time model as the base.

As Lindblom and Cohen observed, much of the world’s work of problem solving is accomplished not through Professional Social Inquiry (PSI), but through ordinary knowledge, social learning, and interactive problem solving.

Conceptual models produced by academics are just one form of knowledge. But, they are only snapshots and like organisational charts, they gradually cease to be relevant. The working knowledge embedded in physical infrastructure, routines, training manuals, values and everyday beliefs of customers and staff are more influential. The institutional environment of suppliers, regulators, media and social conditions also convey knowledge that influence real-time models.

In this respect, the most powerful forms of knowledge are often stories and symbols. The McDonaldization thesis and McDonald’s model as taught in business schools present divergent stories about the same company, one critical, the other laudatory. Perhaps it is no surprise that now you are more likely to find a sociologist in a business school than in a sociology department.

Lessons for Social Science

McDonald’s is applied social science. It is a model tested daily in thousands of outlets and stock markets. However, the lesson is not to imitate McDonald’s, but to integrate social research into institutions to improve people’s ability to create better outcomes. McDonald’s staff use all nine layers of analysis to achieve its objectives and replicate or reinvent itself.

A real-time model may appear like an “iron cage” of rationality, but there is always scope to adapt or challenge customary ways of doing things. Cooperatives, the Khan Academy, Toyota, Wikipedia and many other organisations offer alternative models to McDonalds.

Treating institutions as “dynamic social theories’’ embodying knowledge of how to do things would encourage social researchers to help people make institutions better at solving problems and meeting needs, just as the natural sciences use theories to help people solve problems in the material world. Maybe then we can escape Weberian pessimism by using critical thinking and exploration to transform our models of social science and higher education to improve the human condition at scale.

Titus Alexander FRSA is an independent scholar, educator, and author based in Scotland. He is currently editing a special collection for Frontiers in Political Science on Learning for Democracy, and teaching an advanced apprenticeship in Leading Change. He has worked as director of education for non-profits, a schools’ inspector, a senior education officer in local government, and Principal Lecturer in adult education.

This post draws on the author’s article, Unwrapping the McDonald’s Model: An Introduction to Dynamic Social Theory, published in The Journal of American Culture.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Adapted from Pablo Merchán Montes via Unsplash.

This first appeared on the LSE's Impact blog.