India staying Outside TPP – Not so Fatal

The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement – initiated by the US, has excluded many emerging economies of Asia-Pacific from its remit. This post highlights the potential repurcussions for India of staying outside the TPP and suggests a way forward in terms of greater integration with world economies by pacing up stalled bilateral dialogues.

Since the penning of the new Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) deal – hailed as a success in the United States (US) and Japan – analysts have raised concerns over the absence of the two biggest and fastest growing economies in Asia (India and China) from the TPP. As a US-led regional trade agreement, the TPP was formally initiated in November 2009 under Barack Obama’s administration and concluded – six years later post nineteen rounds of negotiations and several meetings thereafter – in October 2015.

Presently, the TPP includes US and 11 other Asia-Pacific Rim countries, namely Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. With member nations seeking to jointly eliminate the existing tariff and non-tariff barriers on trade in goods and services, promote investment opportunities among members, conform to the newly crafted labour and environmental standards, intellectual property (IP) rights framework and establish a level-playing field for state owned enterprises (SOEs) and private firms (Office of the USTR), the TPP is an agreement to develop a higher global standard for international trade for each member nation.

With its emphasis on an extensive and highly stringent regulatory regime, many scholars believe that the TPP is much more than a free-trade agreement, signalling a paradigm shift beyond traditional trade agreements. Through this agreement, the US seeks to integrate its economy with the Asian economies that have been rapidly expanding (number of free-trade agreements increased from 3 in 2000 to 61 in 2010) over the past few years.

Despite the scale of the agreement, the TPP has been anything but transparent through the course of the negotiating process. Until the text of the agreement was put out in November there was little information about the contents of the agreement. As a result, the TPP has been widely criticized: Vladimir Putin, the Russian President, regarded the closed-door TPP negotiations to be a major deterrent to sustainable growth in the Asia-Pacific. Parliamentarians from countries like Canada and New Zealand have also opposed the ratification of the TPP due to rising concerns among domestic constituents over the lack of transparency and its adverse effects on their economies’ welfare. Paradoxically, the TPP also adopted an ‘exclusion policy’ in regard to many emerging Asian economies such as India, China and South Korea that contradicts the US’ wider agenda to deepen its integration with Asian economies. Yet, as the debate around the TPP continues, it is necessary to examine the economic implications for India.

India – TPP Economic Tie-in

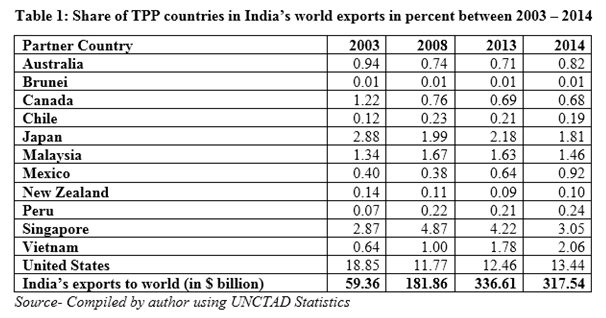

The TPP member nations, particularly the US, Japan and Singapore have been important trade partners for India. India’s trade with 12 TPP countries was recorded to be worth $31.6 billion in 2003, which increased to $152.3 billion in 2014. However, the share of TPP countries in India’s world trade declined from 24% in 2003 to 19.6% in 2014. Despite the declining trend in India’s trade with TPP countries, these nations have been major export destinations for some of India’s products, inclusing petroleum oils and bituminous minerals, textiles, agricultural products (meat and fish products) and motor vehicles. The US accounted for the largest share of 13.44% in India’s world exports in 2014, followed by Singapore and Vietnam with 3.05% and 2.06% shares respectively (Table 1).

Potential Repercussions for India’s Textiles and Labour Market

The TPP agreement aims at the remission of tariffs or zero tariffs (although in a phased manner for some sensitive product categories like agricultural products) for the signatory countries. This will have likely implications for India (a TPP non-member), particularly for its textile and agricultural sectors in terms of trade diversion and significant alterations in global value chains (GVCs). Nearly 48.5% of India’s total textile exports are exported to the US at an average bound tariff rate of 27.3%. However, with the provision of a ‘yarn forward rule’ in the TPP, that makes it mandatory for signatory countries to source their yarn from one of the TPP countries in order to benefit from zero tariff regime, there will be some diversion of India’s textile exports to TPP members. Given Vietnam’s specialization in textiles, Hanoi’s duty-free access to the US market post-TPP will result in India being displaced by the US in favour of Vietnam (a TPP member). On the other hand, to gain the benefits of duty-free market access, Vietnam will have to incur significant costs in setting up its own local yarn/fabric producing unit as presently it sources its raw materials from China. Consequently, the Indian textile sector could benefit from this, although for a brief period (till the time Vietnam sets up its own local production unit for textiles).

This yarn forward rule, coupled with the need to harmonise domestic production standards upwards will considerably alter India’s position in the GVCs for textile products, leading to greater export losses for the country. India’s integration into the GVCs (as measured by foreign value added content in gross exports) has grown from 11% in 1995 to 22% to 2009. Although this level of integration is far below the level of developed economies, it is the third highest among the BRICS economies. India presently complies with the standards laid under the World Trade Organization (WTO). Should India decide to partake in the TPP, it will need to achieve steeper production standards (commonly referred to by scholars as WTO-Plus), which will have an adverse impact on the country’s export industries as it may not be feasible to achieve them in the short-term.

India’s labour market will also have to undergo a sophisticated evolution. The labour market in India is dominated by informal employment that accounts for 92% of the total labour force employment (as per the NSSO data 2011-12). The informal sector does not have to comply with the labour polices set out in the 1998 International labour Organisation (ILO) declaration. In such a scenario, an upward harmonization of labour standards for India’s huge informal sector will be difficult, time-consuming and costly. India is yet to ratify three of the five internationally recognized labour principles as laid down in the 1998 ILO Declaration that have been a basis for the labour standards set out in the TPP agreement.

Way Ahead

By not being a party to the TPP agreement, India will experience adverse effects: in the form of trade diversion and export losses from not complying with stringent regulatory arrangements and production standards. However, India’s strong linkages with most of the TPP economies – Japan, Singapore, Chile, Australia (still in negotiation) and Canada (still in negotiation) – could help mitigate some of these export losses, making it less costly for India to stay out of the TPP. Moreover, the negotiations on other multilateral trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – to which India is a party – need to be expedited as the underlying laws and regulations in that agreement are more accomodative and consistent with the development differences of each member country.

To check the export losses and restricted market access (mainly to the US markets) after the ratification of the TPP agreement, India needs to push forward the bilateral investment treaty (BIT) with the US as it is likely to improve the trade and investment relations between the two countries. Concurrently, India needs to engage in bilateral dialogues with other Asia-Pacific economies like China, Hong-Kong and expand its economic ties with them to bolster its presence in Asia-Pacific.

However, if India intends to join the TPP in future, the government needs to undertake serious economic reforms domestically and raise the domestic production standards to the international standards. This is certainly a long-term process given India’s current level of economic development. Nirmala Sitharaman, the Union Commerce Minister recently stated that India does not plan to be a party to the TPP but is closely monitoring its developments.

Subsequently, India should also pursue its desire to be a member of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum that includes radical trade liberalisation measures and other and regulations that are at par with mega-regional trade agreements like TPP, thereby serving as a stepping stone for its inclusion in multilateral agreements in future. This could be the potential breakthrough for India in agreements of higher global standards.

Preety Bhogal is a Researcher with Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi, India and can be contacted at preetybhogal@cprindia.org