The Politics of Digital Identity: Mapping National Identity Ecosystems for Risks and Vulnerabilities

Emrys Schoemaker and Tom Kirk introduce Caribou Digital’s new project to develop an identity ecosystem mapping tool for use by development and civil society organizations. This tool seeks to understand the ways in which vulnerable groups, such as women and girls as well as refugees, are excluded and how to manage those risks by giving organizations a clearer perspective of identification ecosystems and the motivations and interests of those within them. Its development is funded by Australia’s Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade as part of their support to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting to strengthen access to digital ID for women and girls.

Digital Identification is big news, with many companies, development organizations, and governments developing new systems to manage their relationships with customers and citizens. However, these systems often meet with controversy, such as Kenya’s Huduma Numba and the debate around DNA collection, India’s Aadhaar and issues of data integrity and exclusion, and even the UK’s Verify, where well-designed plans failed to meet targets and accurately identify people.

These controversies are fuelled by the hidden complexity of identification systems. For example, identification systems often have multiple actors overseeing, managing, and using them, each with their own interests and, sometimes competing, agendas. Identification systems are also often linked through data flows and shared registries as well as by overlapping mandates and governance structures. These complexities hamper understanding and engagement, limiting the ability to help prevent unforeseen consequences such as exclusion of and harm to vulnerable groups.

Development and civil society organizations can most strategically and successfully engage with identification when they can clearly see how different systems interact and depend upon one another, and the interests of those involved. Without such insights, they risk their investments and their advocacy strategies may have little effect. They can also unwittingly create or support vulnerabilities that may harm the very users they seek to help.

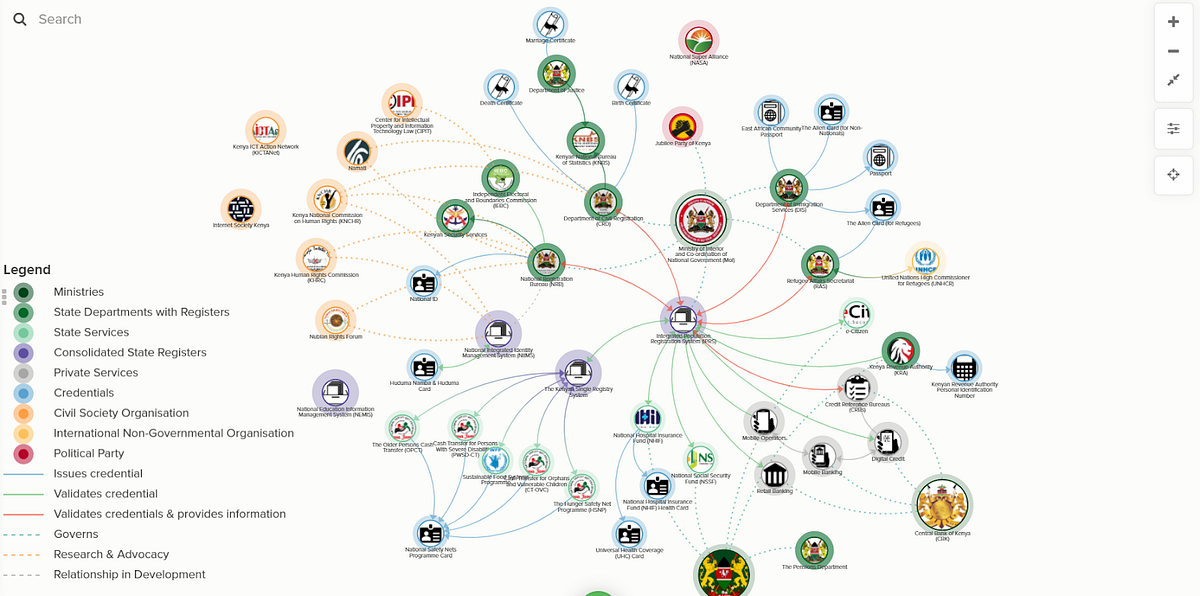

Despite the relevance of this topic, there is a lack of research focusing on both the technical and political nature of identity ecosystems, and those reports that do exist are too often buried in academic journals or made obsolete by the rapidity of change in the field. To address this gap, we’re working to develop a tool to help these organizations map the interdependencies and interests — of technical, organizational, political, and human relationships — underpinning identification systems. We have begun from the premise that individual systems, such as those that issue birth certificates, national identity documents, or bank cards, are part of a country’s larger identity ecosystem (IE). Because systems, registries and credentials exist in a bounded context, they cannot be considered in isolation or separate from the power and politics that surround them.

Identity ecosystems are more than just technical and human relationships. Most identity systems are regulated by laws and monitored by state and non-state authorities. Financial service providers and international development organizations often seek to engage with power holders to change the way they work, but it’s not always clear who the main decision makers are. Similarly, domestic and international civil society organizations clamor for seats at tables where legislation is being debated, while security agencies and the other organizations that comprise the “deep state” often influence IEs in the background.

At the heart of many identification systems is the data of individual human beings. A variety of state and non-state organizations increasingly see this as critical to developing and managing service provision, the granting of rights and entitlements, and enabling digital economies. But personal data is political and can introduce vulnerabilities, particularly for those already at risk, and so the collection of personally identifiable information raises complex questions of privacy, protection, and dignity. Unsurprisingly, it is also often the focus of intense tussles, some of which play out in public with domestic and international media occupying front row seats, but most of which likely occur behind closed doors.

As new identity systems are developed, people register and share ever more information. Accessing these registers and obtaining the credentials they provide can be a relatively frictionless process, such as when hospitals efficiently issue newborns the birth certificates they’ll need to become citizens at 18 years of age. Or it may be a difficult undertaking, as when those with low levels of digital literacy or few foundational IDs try to register with e-Governance websites to apply for further state services. More problematic still, it can be an arbitrary process, as when stateless or persecuted minorities seek asylum in countries that places obstacles between them and their rights.

Accordingly, there is a clear need to view IEs from both the top down and the bottom up, with the lived experiences, concerns, and risks to ordinary people accorded as much importance as the systems’ potentials to support digital economies and grand development plans.

Systems mapping and political economy

A systems thinking approach can bring clarity to the development and civil society organizations looking to support and influence identity ecosystems. It highlights the primary elements within a country’s IEs, that is, the interconnections between them and the purposes they serve. We emphasize identifying the points of collaboration, contention, and influence — the drivers of change — that animate IEs. We will also interrogate the vulnerabilities and risks for which new technologies or programs, no matter how well-intentioned, must account before being launched.

Firstly, maps improve everything from walking trails to identification ecosystems. Visual maps of a country’s various identification systems help people visualize the relationships between them. Kumu, a powerful online systems and social network diagramming tool, allows collaborators to update projects in real time. With it, we can build visually intuitive IE maps that capture countries’ major state, private sector, and international ID systems and the credentials they issue. We can also include the laws, civil society organizations, and authorities that shape IEs while showing the array of physical connections, data flows, and political relationships between elements. These maps will anchor the narrative and digital reports that further unpack stakeholders’ interests.

Secondly, the maps will support vulnerabilities and risk analyses of the studied IEs. Here, the focus will move from an entire IE to important individual identity systems within it, and, eventually, to women and girls’ access to them. Our interest in the latter stems from increasing evidence that, in some countries, women and girls experience unique difficulties when trying to obtain IDs and are sometimes purposefully excluded. This compounds the gender discrimination women and girls face in their everyday lives, prevents them from claiming state services, and bars them from full participation in the economic and political spheres.

The analyses will begin with each country’s IE map and the overall state of the IE, including coverage and reach, and who the IE is designed to serve. Additional questions will explore the content of relevant laws, the social norms that uphold exclusions, the politics underpinning individual ID systems, and the past performance of those in charge of governing them. Focus group discussions with the users of ID systems will add depth to the analyses, providing the crucial bottom-up perspective described above.

This IE mapping is a challenging but necessary step toward understanding and engaging with these increasingly important and complex systems. The identity systems field is at a critical juncture: most countries are trying to establish multiple identity systems. By creating a toolkit that enables others to conduct research, ask pointed questions, and undertake broad analyses, our work will contribute to making legible the systems on which our digital futures will be built.

Emrys Schoemaker is a researcher and strategist with a background in international development programming. Emrys’ research interests are on the use of social media in resource constrained environments, and the social implications of their use. Tom Kirk is Global Policy's Online Editor and a researcher with the Centre for Public Authority and International Development at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Toms’ work investigates political and legal empowerment, and social accountability in conflict-affected regions with particular reference to the DRC,Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kenya and Timor-Leste.

This post first appeared on Caribou Digital's blog and was reposted with permission.

Image credit: Annelieke B via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)