When do Governments Benefit from Non-Compliance with Unpopular EU Policies?

When the implementation of EU policies is likely to be unpopular, do governments benefit from non-compliance? Drawing on a new study, Tim Heinkelmann-Wild, Lisa Kriegmair, Berthold Rittberger and Bernhard Zangl write that while non-compliance can be a successful political strategy, it can also backfire and increase the blame attributed to governments.

Governments cannot always control the domestic political agenda. This is particularly true in the multi-level system of the EU, where governments are often unable to block policies that are unpopular among their domestic constituencies.

Forced to implement unpopular policies, governments risk becoming the target of public blame attributions. For instance, when the EU’s fiscal stability rules mandate budget cuts, governments are often criticised for implementing the required measures. The governments of several southern European countries, which were required to implement austerity budgets in the Eurozone crisis, such as Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy, faced protests and electoral repercussions.

One way to react to the necessity of implementing unpopular measures is for governments to issue threats of disregarding the respective EU policy. We argue that these non-compliance threats are a common but risky blame avoidance strategy. While successful in some cases, they may also backfire and increase rather than reduce the blame governments incur.

The blame avoidance mechanism: passing the buck to the EU

When the public lacks knowledge about EU policymaking, threats of non-compliance should enable governments to shift blame for unpopular policies to the EU. This is because domestic constituencies are often not sufficiently knowledgeable about EU policymaking to attribute responsibility correctly. Governments can exploit this knowledge deficit by framing the EU as responsible for unpopular policies.

Moreover, by issuing threats of non-compliance, governments also re-direct public attention to the EU, which eventually must enforce its policy against the non-compliant member state. Enforcement actions by the EU may generate a ‘rally-around-the-flag’ effect and bolster support for the delinquent government. Blame is thus shifted to the EU.

Take as an example the mandatory relocation scheme for refugees in the EU during the migration crisis. Its adoption prompted the governments of the Visegrád countries to threaten non-compliance and carry out the threat eventually. In the light of the officially sanctioned illegality of this move by the Court of Justice of the European Union, the Visegrád states sought to shift the blame to the EU for imposing a domestically unpopular policy. Their strategy turned out to be successful for the respective governments by fuelling domestic Euroscepticism while bolstering domestic support for national governments.

The blame attraction mechanism: public information and compliance constituents

Threats of non-compliance can also backfire when parts of the public favour compliance with EU rules. Blame will then stick with the government. Threats of non-compliance reveal additional information to the public that the government potentially acts in breach of EU rules. While EU policies are initially salient predominantly for its opponents, the threat of non-compliance mobilises compliance constituencies who criticise the government for tentatively flouting the rules. Public opinion is polarised, and the overall salience of the policy increases. In response, the government is likely to backpedal and eventually implement the policy under rising EU enforcement pressure and pacify compliance constituents.

The Italian government’s threat to disregard EU budget provisions in 2018 demonstrates how threats of non-compliance can backfire. The governing parties, Movimento 5 Stelle and Lega Nord, had been elected on anti-austerity platforms that conflicted with EU recommendations under the Stability and Growth Pact. When the Italian government envisioned a deficit of 2.4% of GDP in its budget plan for 2019, it disregarded EU fiscal rules prescribing 0.8% as a target. By threatening non-compliance with the unpopular EU austerity policy, the Italian government sought to avoid blame for not delivering on its electoral promises.

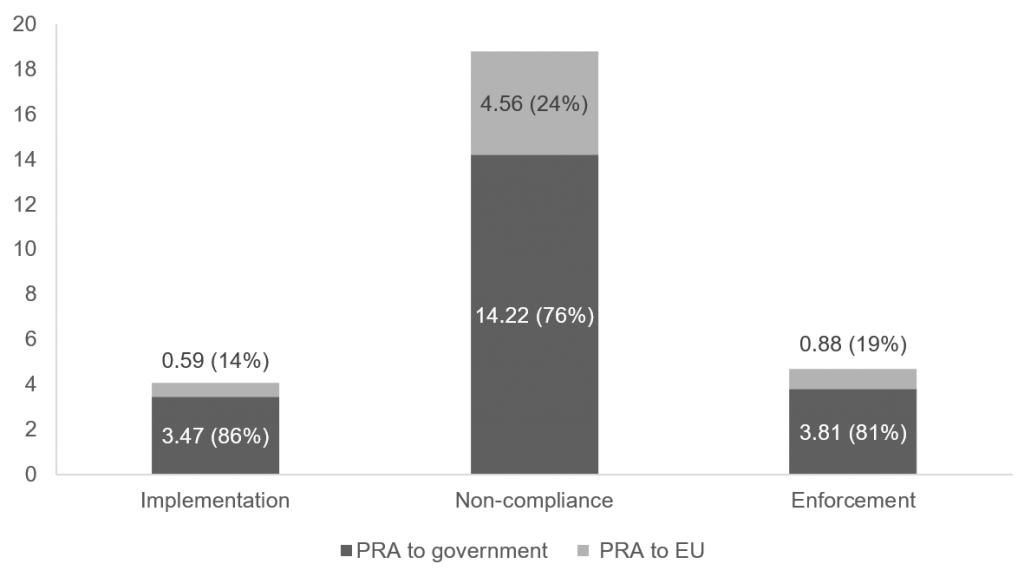

The Italian government’s blame avoidance strategy was ineffective. Comparing public responsibility attributions in the Italian quality press over time shows that threatening non-compliance was counter-productive (see Figure 1). From the beginning, the Italian government was in the spotlight and attracted the bulk of domestic blame attributions. Signalling its intention to defy EU austerity rules did not help the Italian government avoid blame but instead increased blame attributions directed at the government in a veritable blame firestorm. Even when the Commission enforced the austerity policy, blame did not shift to the EU. While blame attributions became infrequent again, the Italian government remained the focal target.

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in West European Politics

What can we learn from this case? When governments face binding but unpopular EU policies, they will often try to avoid blame by threatening non-compliance. Whether this blame avoidance strategy is successful crucially depends on the strength of compliance constituencies favouring the implementation of an EU policy. Threatening non-compliance is likely more effective in countries that exhibit high levels of public Euroscepticism, such as Hungary, than in countries where support for the EU is still rather high, such as Italy.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in West European Politics

Tim Heinkelmann-Wild is a Researcher and Doctoral Candidate at LMU Munich. Lisa Kriegmair is a Researcher and Doctoral Candidate at LMU Munich. Berthold Rittberger is Professor of International Relations at LMU Munich. Bernhard Zangl is Professor of Global Governance at LMU Munich.

This first appeared on the EUROPP blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council

Photo by Karen Laårk Boshoff from Pexels