The Gross Domestic Problem: what would a new economic measure that values women and climate look like?

Measuring progress by Gross Domestic Product leads straight to gender injustice, austerity and environmental ruin. Anam Parvez Butt and Alex Bush introduce a new Oxfam discussion paper that aims to encourage debate about alternative metrics, and calls on advocates to join the “Beyond GDP” movement.

Since its official adoption at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, Gross Domestic Product or GDP has become the single most important indicator of economic and social progress.

However, as our new discussion paper reflects, it is not just a metric, but a patriarchal, neocolonial value system imposed on the world for decades that equates wellbeing for all with the production of riches for some, and at huge cost.

As the renowned ecofeminist Vandana Shiva says: “The transformation of value into disvalue, labour into non-labour and knowledge into non-knowledge is achieved by the most powerful number that rules our lives: the patriarchal construct of GDP, gross domestic product, which commentators have started to call the ‘gross domestic problem’”.

Oxfam’s paper published today, a collaboration with feminist and decolonial scholars Lebohang Liepollo Pheko and Dr Ritu Verma, builds on the critical work of many other feminist economic, wellbeing, degrowth scholars, movements and activists to show how GDP upholds and acts as the guiding compass of an economic system that creates vast inequality – particularly for women, and for people in the global majority – as well as environmental degradation. The paper outlines the problems with GDP and sets out how we can start to design something better.

What does GDP miss and why is it so damaging?

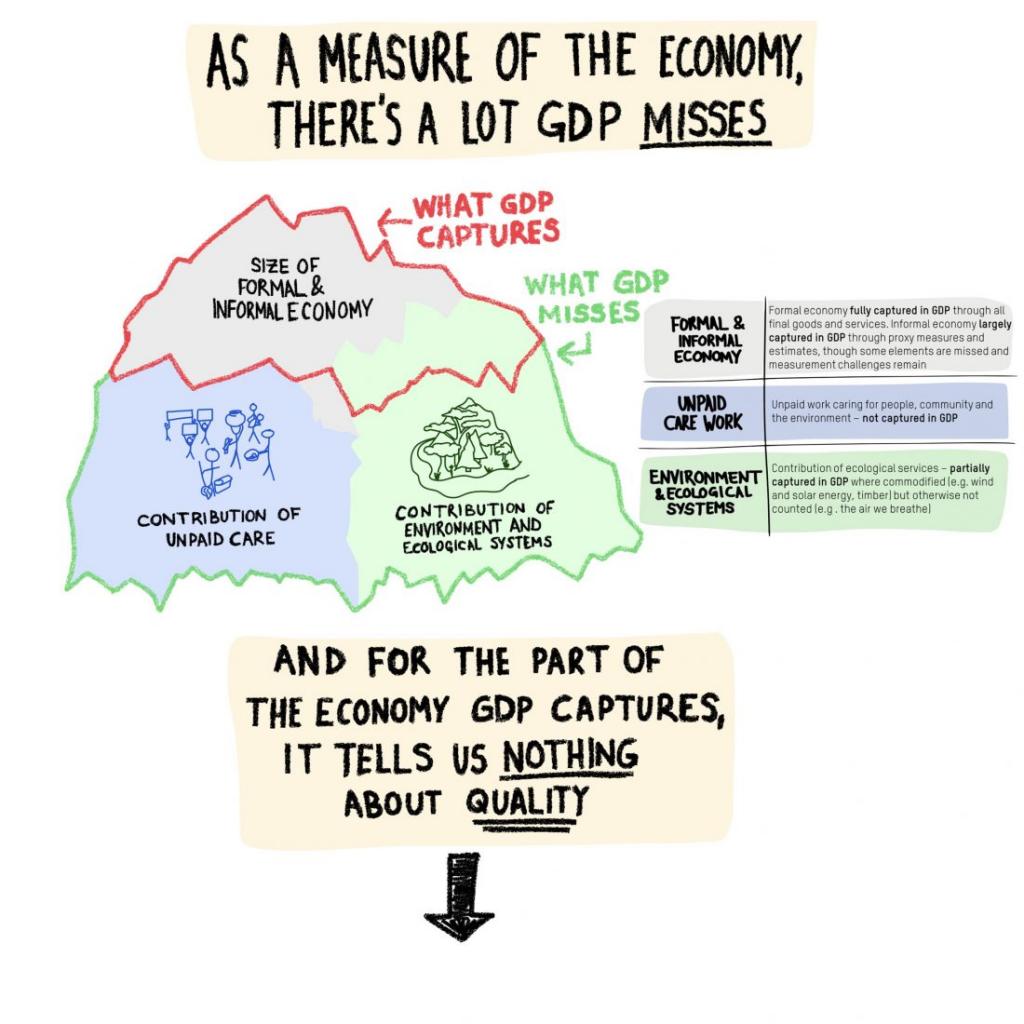

GDP excludes much of women’s contributions to the economy and society: our calculations reveal that almost half (45%) of the total number of hours worked around the world, are in unpaid care work, excluded from GDP, despite the economy’s dependence on this vital labour. It ignores the value of peace and the air we breathe; in fact, environmental damage such as oil spills can even increase GDP through clean up efforts, yet simply not polluting the ocean counts for nothing. A singular focus on GDP has played a key role in displacing Indigenous knowledge systems, principles of care, solidarity and respect for the environment from dominant economic thinking.

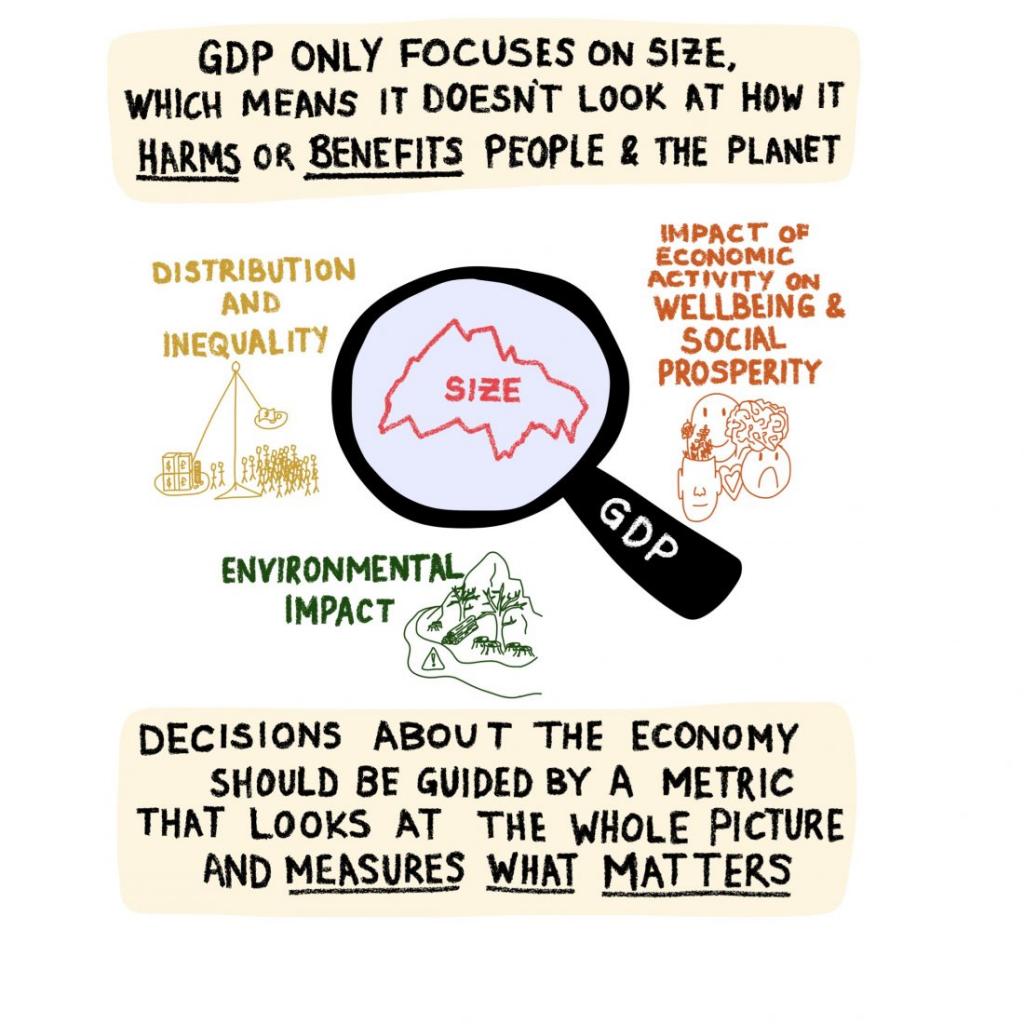

We show how our fixation with GDP growth is directly leading to policies and practices such as austerity, privatisation, and extraction of resources and labour that deepen inequalities and fuel the intensity of crimes against the environment and people, particularly marginalised women and Indigenous people in the Global South.

Focus on GDP is a key rationale for austerity measures, such as deep cuts to spending on public services with the aim of cutting debt in relation to GDP and boosting growth through increased private investment. Austerity, which is soon expected to affect 85% of world’s population, is a form of violence on those living in poverty, particularly women and girls who disproportionately rely on public services and public sector employment. For instance, ten years of austerity in the UK has been accompanied by a fall in life expectancy for women in the most deprived areas largely from minority ethnic and racial groups. The narrow focus on GDP growth also results in policies that drive inequality, as it delivers ever-greater profits and capital for the owners of wealth and countries in the global minority on the backs of ordinary workers, women, and Indigenous peoples.

Replacing GDP: how can we measure what matters?

The paper highlights that, in growing recognition of the shortcomings of GDP, over a number of years, various alternatives have been developed. Despite these welcomed efforts, very few of today’s alternative frameworks that have gained traction can be said to be explicitly feminist or decolonial. Many are actually “false alternatives”, still rooted in GDP growth. Sustainable Development Goal 8 for example still explicitly targets economic growth whilst even the “beyond GDP” SDG indicator 17.19 is just a “complement” to GDP. More attention needs to be paid to other approaches such as Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index, as well as Aotearoa/New Zealand Wellbeing framework shaped by Indigenous Maori perspectives on wellbeing.

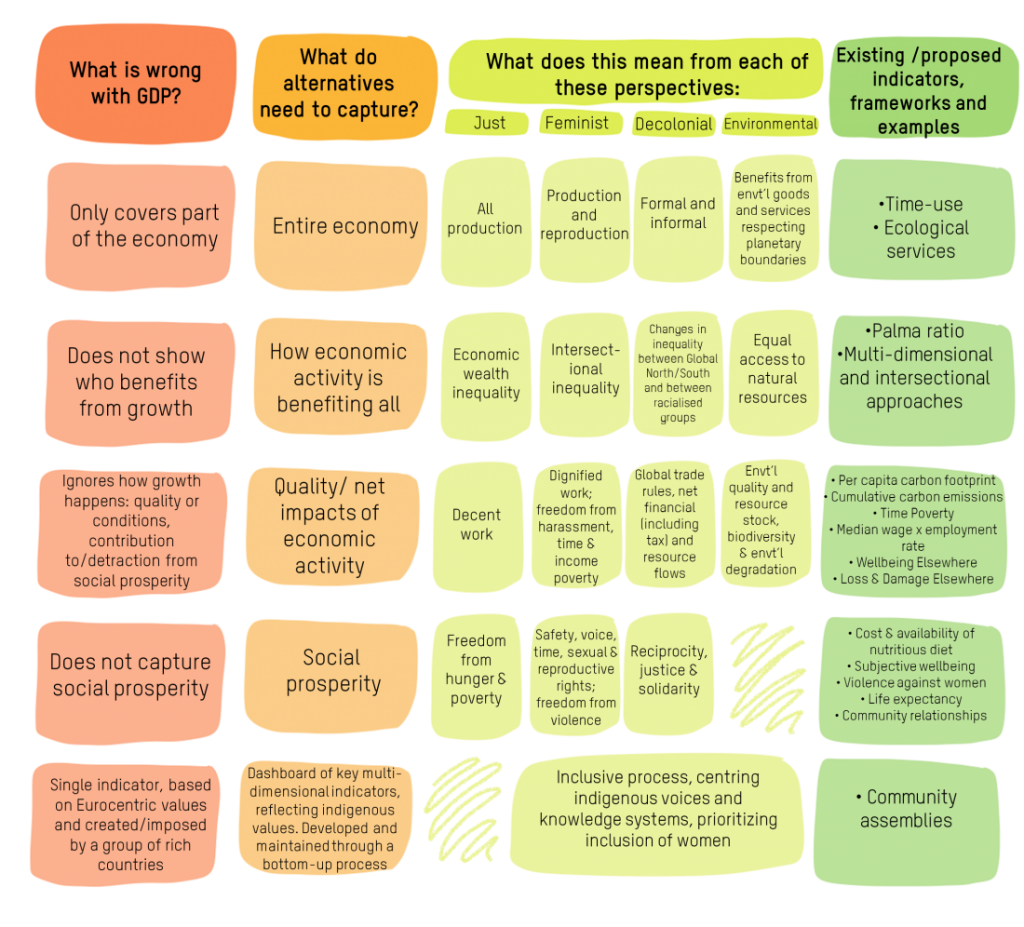

So how can we design a better measure? Informed by the perspectives of feminist and decolonial thinkers we identify five core dimensions and key indicators to consider.

- Measure all economic activity: this must include paid and unpaid, formal and informal, production and services: a critical indicator is time use – a measure pioneered by feminist economists that looks at how people spend their time and captures the labour put into unpaid care work. This needs to be disaggregated by gender, age, income, race, other dimensions to enable an intersectional analysis. Another key indicator is ecological services and ecological diversity that enable our planet, economies and societies to thrive.

- Consider How economic activity benefits everyone: looking at intersectional and economic inequality, including how this shifts within and between countries in the Global North and Global South, as well as between class, gendered and racialised groups. Here the Palma Ratio is one useful indicator that can be complemented by other multi-dimensional and intersectional approaches.

- Assess “wellbeing elsewhere”: in other words the positive or negative impact of a country’s policy decisions and resource use on other countries. This should not only measure impact in the present and future but also how much it redresses past injustice, highlighting for instance climate reparations needed from rich polluters to countries in the Global South.

- Evaluate all dimensions of well-being and social prosperity, such as:

- nutritious diets (e.g. the share of the population that can afford a healthy diet), flagged by Indian economist Jayati Ghosh to her fellow members of the UN’s High-Level Advisory Board on Economic and Social Affairs ;

- Subjective wellbeing: How people evaluate their own life;

- Violence against women and girls (e.g. share of women and girls subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner in the previous 12 months).

- Community relationships and support (sense of belonging to local community, ability to rely on others in times of need).

- Local and traditional knowledge and perspectives: Indigenous people and women from the Global South need to be centred not only the creation but also implementation of alternative metrics. Indicators reflecting local knowledge and perspectives need to be meaningfully included and placed front and centre in the design, implementation and analysis of beyond-GDP frameworks. These must be rooted in a recognition and acceptance of – and commitment to repair – the damages caused by colonialism and economic imperialism.

What is blocking us from replacing GDP?

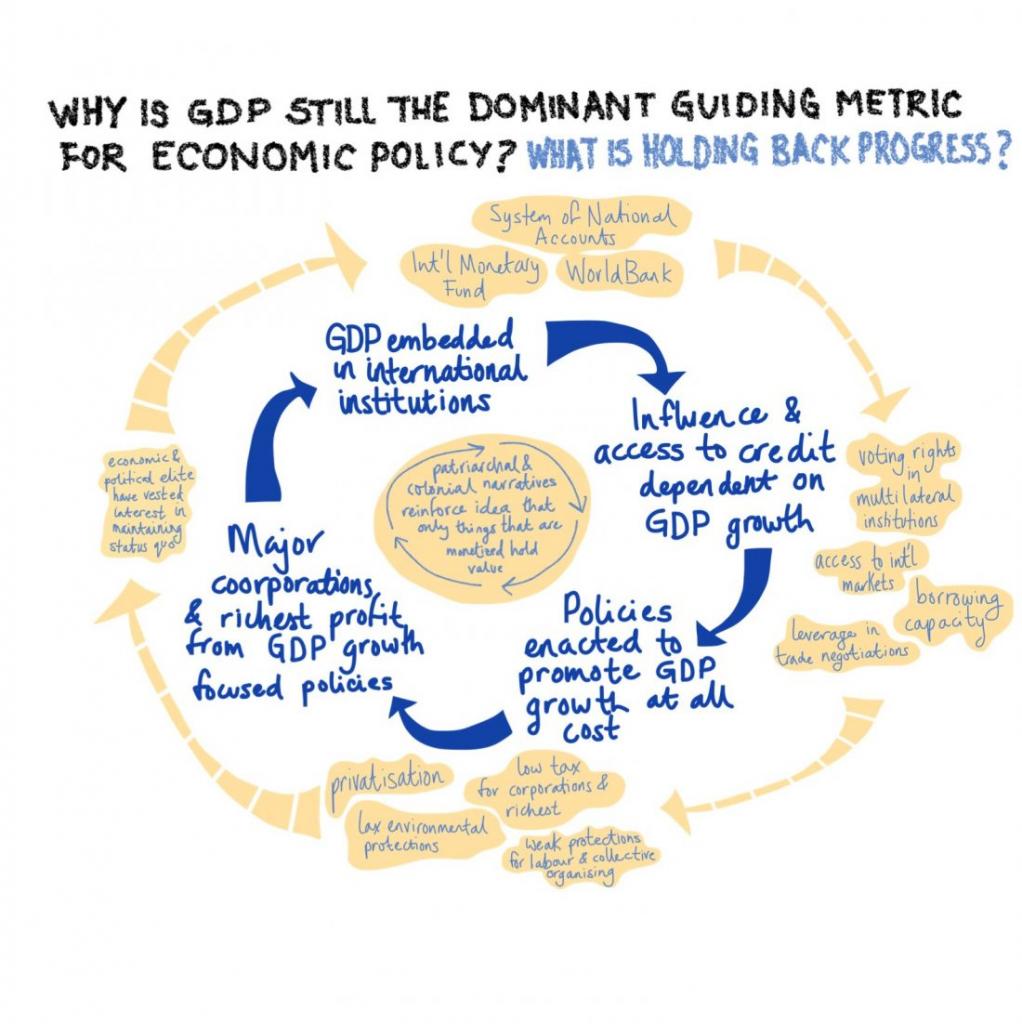

The paper also identifies four key obstacles to replacing GDP with something that works better for people and planet.

- False narratives around the economy. The “economy” is a social construct, and dominant narratives suggest that it only includes the market economy, meaning that only activities and resources that can be owned, controlled or sold are of value. Alongside this, there are narratives around women “under-participating” in the labour force when they actually do more hours of total work (paid and unpaid) than men. Such beliefs are deeply entrenched in international organisations such as the UN, World Bank and IMF.

- The entrenchment of GDP in formal frameworks such as the System of National Accounts (an international set of recommendations on how to measure economic activity) and in loan conditions, trade and investment agreements, and the eligibility conditions for powerful economic groups like the G7 and OECD, mean that countries depend on GDP growth for improved access to credit and power in international negotiations, so are pushed to promote GDP growth at all costs.

- GDP reinforces the power and vested interests of the (mostly male) political and economic elite who then act as a powerful barrier to change.

- The lack of a common language and consensus among critics on a suitable alternative. GDP also has ‘single indicator appeal’, whilemulti-dimensional frameworks of wellbeing have too many indicators, so it is hard to tell a compelling story. Our paper joins others in highlighting the need for a clear, smaller set of key indicators.

Illustration by Alex Bush

So how can we dislodge GDP from its dominant position?

Progressive voices for change need to bolster efforts to get meaningful alternatives to GDP on the political agenda, and push policy makers to invest meaningfully in, scale up and foreground GDP alternatives. We identify three key strategies to do this:

1. Shifting the narratives Challenge the notion of what constitutes ‘the economy’, to move away from valuing only production to valuing sustenance and regeneration – across academic curriculums, political debate, popular media and advocacy.

2. Building consensus around what radical and real alternatives look like and pathways for getting there ensuring feminist and decolonial critiques and principles are at the centre and women and Indigenous people are central to the design of future indicators. This could include ‘cornerstone’ or key indicators of social and ecological prosperity.

3. Pushing governments and institutions to invest in testing, piloting and scaling real alternatives, working with cities, regions and countries to build alternative frameworks and supporting statistical infrastructure, drawing on growing body of learning

Now is an important moment for change: the international standard System of National Accounts that centres GDP is being revised before 2025 and the SDGs are also approaching their mid-point review.

We must seize this moment to pursue a radical “beyond GDP” agenda: the battle to dislodge this regressive measure as the guiding metric for social and economic policy is going to be one of the most important tasks for anyone who truly values people and planet.

Anam Parvez is Head of Research at Oxfam GB; Alex Bush is a Researcher for Valuing Women’s Work at Oxfam GB

Read the full paper: Radical Pathways Beyond GDP: Why and how we need to pursue feminist and decolonial alternatives urgently

This first appeared on From Poverty to Power.