Can Biden Really Make Gas Cheap?

A mighty, autobahn-devouring Audi sits outside an invite-only energy discussion at the World Economic Forum in Davos, unwilling to discuss its 93-octane drinking problem. Inside the Chatham-House-Rules-constrained second-floor space, a diplomat mused: “it all comes down to leaders and liters,” but when and how can the former influence the price of the latter?

Ed, just from a political perspective, do you think the president of the United States going into reelection wants gas prices to go higher?

– Then-President Barack Obama to Fox News’s Ed Henry on 6 Mar. 2012 (8 months to the day pre-re-election)

As someone interested in economics and history and policy, it’s fascinating to be traveling back and forth to Riyadh (as I am recently) at the dawn of an American election year. Travel to a founding land of OPEC (and reliable producer of between 9 and 11 million barrels a day) inevitably evokes thoughts about energy policy and global markets. And energy is certainly something that shows up frequently in Biden’s stock talking points this winter… but can Biden (or any incumbent) really change gas prices, given that neither Biden nor traders can create ready-to-ship crude from thin air? What have other presidents done? And, to risk running afoul of decades of campaign trail conventional wisdom: do high fuel prices really doom incumbents?

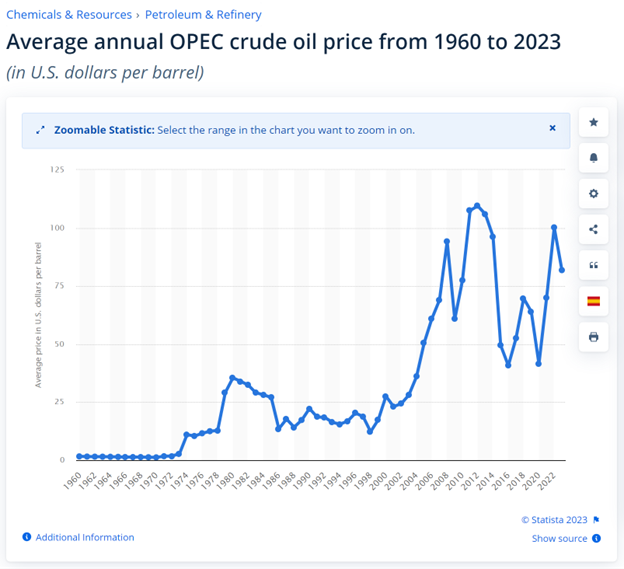

Above: Gas wasn’t a big deal in American politics before 1973; this is why. Graphic: Statista.

Superbiden or Scranton Joe?

I’ll start with the Seinfeldian prompt: What’s the deal with… election-year presidents?

Well, Jerry… the deal is that for three years they toss their hands in the air and say, “It’s markets, I can’t do anything about it!” but in that final year it’s cheap gasoline,[1] a chicken in every pot, and two cars in every garage.[2] So which is it? What does the President have (or not have) the power to do as to fuel prices? Is he Superman or Clark Kent? Are gas prices even a big deal in 2024?

Gas prices are clearly a big enough deal for west wing speechwriters to bend the truth until it breaks. For instance, on September 23, President Biden proudly announced at a DNC-sponsored, campaign-like event in Washington that “Gas prices are down, $1.30 a gallon. And in 41 states plus the District of Columbia, the average gasoline price is less than $2.99.” That would have been really impressive if true! Unfortunately, it wasn’t true. National retail price averages for regular gas that day were $3.689 (or between $3.65 and $3.725, depending which index is used), which clearly exceeds $2.99.[3]

As with Superman and Clark Kent, the relationship between Superbiden and Scranton Joe is misunderstood. Like the comic book hero, he’s actually Superbiden and Scranton Joe at once.

And this is where I put on my law professor hat. You see, presidents have in the Constitution these incredible, sweeping, imperfectly-defined Article II powers.[4]

While the courts may theoretically limit or temper the executive,[5] the courts have correctly and thoughtfully paused before trespassing on what are clearly Article II territories: a president acting in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief, a president acting as a diplomat and exercising his treaty powers, or a president as a check on the legislature when exercising his veto power over legislation (with the narrow exception of the rejection of the line-item veto as an expansion of the veto power[6]).

To quote Justice Blackmun,[7] “unless Congress specifically has provided otherwise, courts traditionally have been reluctant to intrude upon the authority of the Executive in military and national security affairs.” And Blackmun is right to point out[8] that “As to these areas of Art[icle] II duties the courts have traditionally shown the utmost deference to Presidential responsibilities.”[9] So President Biden could run around doing everything within his Article II powers to save people pennies at the pump in a desperate, pandering tour of the policy landscape. But… it might not be a good look.

Just like Clark Kent is underneath always Superman, Scranton Joe can always flex these Superbiden powers. And, not coincidentally, it’s exactly these Article II muscles (military/C-i-C,[10] diplomatic/treaty,[11] and vetoing legislation[12]) that could conceivably, utilized carefully, change the price of oil and refined petroleum products in the United States. But using presidential powers to temporarily, even if popularly, distort certain markets runs counter to historical presidential norms to directly intervene and tamper with petroleum markets from the Oval (and these norms are a good thing!).

This blog argues that, while gas prices may indeed be an election year problem, without extraordinary and unprecedented adventuresome use of presidential powers (and an uncharacteristic-for-Biden abandonment of presidential standards of presidential transparency, policy prioritization, and general behavior) this executive can do little to reduce retail prices with predictable and prompt effect.

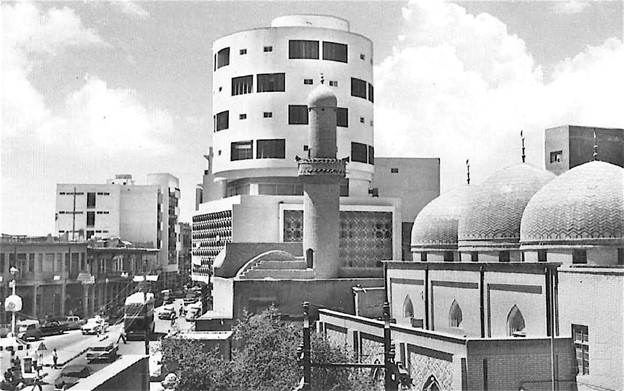

Above: The bustling 1960s city of Baghdad, where OPEC was founded. The Marjan Mosque is in the foreground, right. Iraq’s petrocentric economy exhibited some of the highest 1960s growth rates, with 8% annual growth being a plausible, if now historically-debated, number cited (for more on this statistic’s provenance, see M. Zainy, The Iraqi Economy under Saddam Hussein: Development or Decline? (Al-Rafid Publishing London, 2003). This photograph was first published in Iraq in the 1960s and is now in the public domain; learn more about rights involved here.

A Brief History of Modern Oil

Though OPEC was founded in Baghdad, originally with a membership of only five nations (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), in many ways Riyadh is the center of gravity of OPEC discourse. It is the most stable in the post-crisis era, 1973-2023, in both political system and continuity of governance; it has an ambient gravitas as a capital that Tehran, Baghdad, and Caracas lack completely, with Kuwait City in a distant second place. And, perhaps most importantly, the Saudis have shown a leadership and nuance in OPEC production discussions often lacking from other cartel member states.

Live by the sword, die by the sword, a quippish transliteration/simplification of Matthew 26:52, has been around for a couple millennia, and we’re now fifty years into the era of “live-by-the-pump, die-by-the-pump” fuel price politics in America (a phrase often linked, but perhaps apocryphally misattributed, to Ben Stein, then an up-and-coming Republican speechwriter and strategist during the 1973 oil crisis in the waning days of the Nixon White House). This prevalence of retail unleaded prices in the public discourse is unsurprising, as fuel prices (for those who do not yet drive EVs) are a cost-of-living indicator and inflation indicator that stands out in the distorted as-perceived CPI basket of “kitchen table politics.”

I’ve been thinking about commodities markets for a long time. Years ago, my PhD dissertation at the London School of Economics was entitled “Three Frameworks for Commodity-Producer Decision-Making Under Uncertainty” (despite the thrilling title, the film and television rights are still available!). The story of commodity producer incentives and tactics during and following the 1973 oil crisis are no less dramatic and intrigue-infused than a summer action movie, and autumn 1973 is the genesis of modern oil. It is not uncommon for incumbents try to calm the masses with affordable high-octane refined petrochemicals, but let’s (to use an automotive metaphor) look under the hood, shall we?

Above: Biden pledges to keep gas prices low during and through the election season, but is that really a promise the White House can credibly make? Screenshot; article published 14 Sep. 2023.

Article II and Commodities Markets

To understand these dynamics, one must travel back in time not just to the Nixon administration, but further back in history to understand how much control U.S. presidents really have over commodity prices and whether it’s fair or desirable for presidents to be perceived as living or dying by the pump.[13] And, long before oil, presidents made promises.

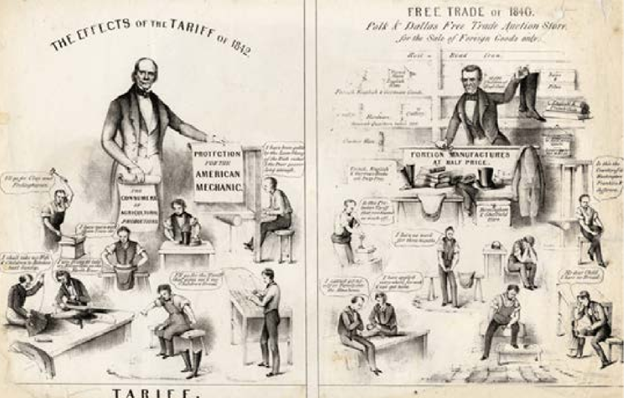

Above: A bifold or “two up” poster, the common election-year communication of the day, illustrates the supposed benefits of protectionist tariffs (left) and ponders the implications of cheap imports (right). Creator or publisher unknown; copyright expired under the pre-1924 blanket public domain rule.

Even in very early U.S. elections, candidates pledged to “do something” (what exactly “something” meant varied between era and circumstance) about the price of commodities. Adams pledged to create a new tariff system, making commodities more affordable. Jefferson did his best on behalf of the voting livers, making British-Jamaican rum marginally cheaper by reshuffling a reciprocal tariff regime and making French wine substantially cheaper by increasing its available quantity, mostly through allowing its import at a larger number of ports, notably in Massachusetts. Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, all sons of Virginia, worked in various ways to subsidize the cultivation of Virginia tobacco, both with cross-subsidy tax policy and with import substitution arguments (Madison had helped envision Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 and was eager to use tariffs to stimulate domestic production, as discussed in Madison’s letter to Campbell on 18 Sep. 1828).[14] Today, the U.S. subsidizes the production of sugar in three fundamental ways, direct subsidies, by setting a price floor, and by taking the most dollar-costly negative environmental externality of that business and socializing those losses (through federally-funded cleanup of the Everglades[15]); oddly, we also heavily subsidize sugar’s main domestic substitute, high fructose corn syrup, though this support is partially hidden within the more nebulous sections of existing ethanol subsidies.[16]

Why, if this has been going on for so long, do I flag the autumn of 1973 as the start of modernity?

Well, Americans did not think much about the cost of petroleum products pre-1970. During the oil crisis,[17] however, gas prices topped the news, often appearing “above the fold” in major newspapers, only to be dislodged in 1973 by the most important judicial news (such as Roe v. Wade), domestic political news (such as the Saturday Night Massacre), and foreign affairs topics (such as the winding-down of the War in Vietnam). Though younger readers may not remember this context, the 1973 oil crisis was not some uniting asteroid-headed-toward-earth, totally-unexpected exogenous event; rather, it was in large part related to a change in trade policy frameworks, principally led by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, an important voice within OAPEC (the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries).

The basic mechanism was simple. Nations that had supported Israel[18] during the Yom Kippur War (also known as the Fourth Arab-Israeli War or the October War) on the Sinai and in the Golan Heights (then Israeli territory) would be punished through new supply constraints (export embargoes), bifurcating along a new fault line the world market for refined petroleum products (Soviet-aligned states, which included states hostile to Israel during the Yom Kippur War, already effectively operated in a separate petroleum market). The UN-proposed ceasefire, known as Resolution 339, a sequel to Resolution 338 in topic and substance, passed unanimously less China’s abstention; it proposed a return to initial positions at the ceasefire’s effect, but did not, importantly, consider economic policy change by third-party actors.

More Recent History

The Obama years were prosperous, a gilded age coming off the housing and financial crisis of 2008. This was also a time of substantial focus on transportation and renewable energy, including the “Car Czar” Steve Rattner and west wing briefing time spent on theretofore-obscure energy topics like high-pressure fracking and battery chemistry research (while expansion of fracking began under Bush 43, its contribution to the total energy production table came primarily under Obama). Both the Obama-Biden and Trump-Pence (2017-21) administrations ended their terms with fuel cheaper than when they took office by fifteen to twenty cents per gallon.

Questions swirled during the Obama years and Obama largely dodged the issue as either outside the sphere of Presidential control or a low priority compared to employment and recovery from the financial crisis.

That said, Obama faced a recent re-election battle where gas prices were often mentioned. I’ll let three quotes leading up to the re-election season in latter 2012 speak for themselves.

[Foreign producers] want to go in and raise the price of oil because we have nobody in Washington that sits back and says you’re not going to raise that f🍆cking price, you understand me?[19]

- Donald Trump in April 2011

President Obama must announce today … that he is firing Secretary Chu and replacing him with a pro-American-energy appointment. If he doesn’t, then the American people will know the president is still committed to his radical ideology, which wants to artificially raise the cost of energy.

- Newt Gingrich in March 2012

[T]he cost of gasoline has doubled. Not exactly what he might have hoped for. … He’s said it’s not my fault. By the way, we’ve gone from ‘Yes, we can’ to ‘It’s not my fault.’ Well, this is in fact his fault.

- Mitt Romney in March 2012

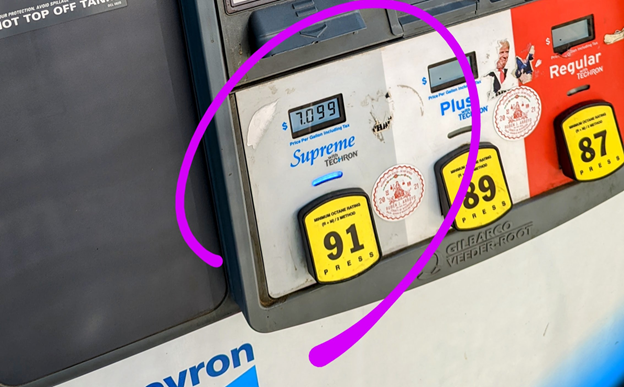

The honor (sarcasm here), however, of the highest gas prices on record in real and nominal terms, as measured by the average weekly retail gasoline price index, belongs to the Biden-Harris administration (2021-2?). In June of 2022, the index hit $5.07 for a gallon of typical unleaded.

Above: A Chevron station off Interstate 10 near Chiriaco Summit charges over 7 USD per gallon for high-test unleaded gasoline in June of 2022. For those overseas trying to do the conversion, this would be equivalent to about a pound fifty or 1.75 EUR per litre; importantly, California gasoline (pictured) includes both federal and state taxes in the displayed price. Photo and purple annotation by the author.

The Biden-Harris administration also saw the largest jump in prices at the pump ever in a first year in office, from $3.10 (intrayear blended average) in 2021 to $4.06 (same measure) in 2022. Unlike during his time as Vice President (under Obama), the White House with Biden at the wheel has not enthusiastically expanded oil and gas production domestically and has not reframed the issue in terms of national security or defense.

Remaining Options for Influencing Petroleum Prices

But what could Biden do if he didn’t want to just look competent and effective, but wanted to influence prices at the pump somewhat directly?

Well, I think he’s trying some of the things he can do without really flexing those Article II powers or being outside any major presidential behavioral guardrails.

On October 18, Biden substantially relaxed sanctions on one of OPEC’s founding members, Venezuela. He’s placed some limits on new potential drilling sites, but this does not substantially change pre-election exploitation of domestic opportunities. The Biden administration had been easing sanctions on Iran, a large supporter of Hamas in terms of both rhetoric and matériel, but has had to reverse course here and admit its softer stance on Iran is out of step with Congress; in early November, a month after Hamas attacked Israel and as disastrous polling came out for Biden (both head-to-head against Trump in a theoretical match-up and generally in terms of likely-voter enthusiasm), the House voted 342-69 to impose punishing penalties on foreign ports and refineries that transfer or re-sell Iranian oil. It is unclear, however, how effective the cleverly-named “SHIP” (“Stop Harboring Iranian Petroleum”) bill will be, given that roughly 80% of Iranian oil goes to China and the Chinese are notoriously-opaque in their reporting of where the oil for refined products and finished goods (such as items made from plastic) come from.[20]

The demise of the Keystone XL Pipeline plan had an effect on the long-term infrastructure plan for U.S. energy, but in the meantime much of the oil that would have moved to the U.S. from Canada via the pipeline will be moved through existing pipes, ships, and trucks.[21] The Biden administration seems to have been betting that Saudi Arabia would announce increased production for 2024, but there is little reason for the Saudis to rush to produce excess oil and the U.S. has little leverage to change the Saudi production profile in the short-term (Saudi oil production has oscillated in recent years in a relatively narrow band from 9.125B barrels to 10.566B barrels). Near the close of 2022, the U.S. pressured its G7 allies and Australia to not allow their commercial fleets to transfer or deliver to terminal any oil from Russia changing hands at over 60 USD per barrel, but Russia has shown surprising resiliency and has been using a “shadow fleet” of up to 600 tankers to transport oil to be sold at closer to the 70-80 USD per barrel median world clearing price during the period. If Russia is already evading the sanctions from late 2022, Republicans interested in a more Russophilic policy path may see an opportunity to relax or dismantle these sanctions, in the process opening the U.S. market to substantial volumes[22] of Russian oil for the first time since the recent hostilities in Ukraine began.

Presidential influence over markets, even markets adjacent to or wholly within highly regulated industries (like banking, energy, or insurance) is limited and while low commodity prices (for instance, at the gas pump) may be popular, timing them to sync up with election day is challenging even under the very best of circumstances with the most overt, severe market interventions. To do so under more difficult circumstances and using butterknife tools (i.e. not direct market intervention) requires luck or magic, and the Biden administration seems like an exhausted policy team that has been running low on both for a long time. Ninety-day tax holidays, Venezuelan imports, and another dip into the strategic petroleum reserve might make differences of pennies and nickels per gallon (no more than pennies in the Venezuelan case), but more substantial moves in oil prices are unlikely to come from any single executive action (or even policy framework) and more likely to come from global, persistent market forces… especially when the incumbent is not someone known for casually or unilaterally departing from established norms and testing his Article II powers to the limit.

In sum: You can cast a vote based in part on fuel prices in early November, but the price you see at the pump probably isn’t Biden’s doing.

Karl T. Muth is a law-and-economics scholar who teaches at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. At Northwestern, he teaches a popular week-long annual intensive seminar at Northwestern’s Pritzker School of Law in addition to more traditional graduate economics and public policy coursework. This blog embraces, and expands upon, some of the political economy topics touched on in his recent lectures at Northwestern.

Top image: Photo by the author.

Notes

[1] Back in the summer of 2022, Biden pushed Congress to create a federal tax holiday on gasoline; even if the $0.184 (that’s eighteen cents if we round to numbers used by real non-economist non-wonk people) were fully returned to the consumer, that’s under three dollars back when filling up a typical family car’s fuel tank.

[2] Hoover circa 1928.

[3] For those who claim this was merely an oversight or a typographical error, in the same speech Biden claimed “We have a 3.7% unemployment rate, the lowest in 50–more than 50 years…” which is certainly untrue, as the figure was lower as recently as 2020 and lower half a dozen times in the past five years.

[4] My fellow legal scholars will notice I’m invoking the so-called “vesting clause thesis” here. While reasonable minds can differ as to the original intent of vesting diplomatic, negotiation, and treaty powers in the Oval Office, that’s another fight for another blog. For those unfamiliar with, but curious about, the macrodispute, compare Mortenson (of Michigan)’s view with Cass Sunstein (of Harvard)’s view, the latter being much closer to mine. See J. Mortenson, Article II Vests the Executive Power, Not the Royal Prerogative, 119 Colum. L. Rev. 1169 (2019); but see C.R. Sunstein & A. Vermeule, The Unitary Executive: Past, Present, and Future, 2020 Sup. Ct. Rev. 83 (2020). It is disputed among historians and law professors whether Federalist No. 63 was written by Hamilton or Madison, though I subscribe to the theory it was written by Hamilton, in part because of its idolization of the executive-as-representative concept and speaking of “pure” democracies (“In the most pure democracies of Greece, many of the executive functions were performed, not by the people themselves, but by officers elected by the people, and representing the people in their executive capacity” with emphasis as in the original), and in part because of its seeming consistency with Federalist No. 70, which historians generally agree was written by Hamilton and speaks of a very similar executive.

[5] Or a recent past executive, in the case of “The Donald.”

[6] Some readers are likely too young to recall the uproar in the 1990s over line-item veto powers, but it was a big deal at the time. For economics and policy scholars, see generally J.R. Carter & D. Schap, Line-Item Veto: Where Is Thy Sting?, 4 J. Econ. Perspectives 103 (1990); for legal scholars, see also M.T. Kline, The Line Item Veto Case and the Separation of Powers, 88 Calif. L. Rev. 181 (2000). For detail on the questions at bar, see The Line Item Veto Act [of 1995-6], 110 Stat. 1200, 2 U.S.C. § 691 et seq. (1994 ed., Supp. II) and compare Raines v. Byrd (Rehnquist, C.J.) with Clinton v. City of New York (Stevens, J.). 521 U.S. 811 (1997) and 524 U.S. 417 (1998), respectively. For analogous controversy at the state law level, see Silver v. Pataki, 755 N.E.2d 842 (N.Y. App. 2001).

[7] Dept. of Navy v. Egan, 484 U.S. 518, 530 (1988) (Blackmun, J. citing par exemplar Orloff v. Willoughby, 345 U.S. 83, 93-94 (1953); Burns v. Wilson, 346 U.S. 137, 142, 144 (1953); Gilligan v. Morgan, 413 U. S. 1, 10 (1973), Schlesinger v. Councilman, 420 U.S. 738, 757-758 (1975); Chappell v. Wallace, 462 U. S. 296 (1983)).

[8] Dept. of Navy at 529-30.

[9] Citing United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 710 (1974).

[10] Commander-in-Chief, or legal shorthand for the military command powers more generally (sometimes including, but sometimes importantly excluding, use of the “nuclear football” in either a response or first strike context).

[11] It is unclear exactly how far the treaty power extends and parts of its durability remain constitutionally untested; for instance, a president clearly has the power to sign the treaty to join NATO, but can he unilaterally leave NATO (as Trump has suggested he might do)? This dichotomous quandary, that the President may be able to unilaterally do things she cannot later undo alone, remains unresolved.

[12] This could conceivably include taxes on fuel or constraints on production, both of which would potentially raise prices at the pump for consumers.

[13] I should note that, despite Stein’s alleged adage, multiple studies, recently Sinha et al. (2012), conclude that oil prices are not significant in predicting incumbent advantage or incumbent penalty in U.S. presidential elections.

[14] If you’re interested in what things cost back then, this is a great resource. If you look at prices in England, you’ll need to know what GBP was worth in relative terms, and this is a handy tool for that.

[15] I’m referring not just to the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, which received another $447M in the 2023 Omnibus Appropriations legislation, which is only part of the public funding used for this purpose.

[16] The ethanol subsidy, or corn ethanol subsidy specifically, does not come from a single piece of legislation; the modern subsidy framework starts with the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, followed by the Energy Policy Act of 2005, and augmented with specified minimum production quantities and price supports in the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007; in essence, this subsidizes the first 15 billion gallons of corn-based ethanol produced each year directly and subsidizes further production indirectly.

[17] I’m referring to the ’73 crisis here, though the ’79 crisis also had political implications (it is difficult, if not impossible, to quantify how much of Reagan’s landslide victory over Carter is attributable to the latter’s mismanagement and mismessaging around fuel prices).

[18] Nixon made an emergency appropriations request to Congress for $2.2B in funds for Israel in early October 1973.

[19] Censoring aubergine added by the author.

[20] For context, the 11.5M barrels per day of oil China imports is about the size of Russia’s total national production (not net production, this includes its domestic consumption).

[21] This would have happened in the interim whether the Keystone XL Pipeline was completed or not, as it would have taken years of (litigation and) construction and approvals and pressure-up/pressure-down testing before the first million barrels moved through it.

[22] Russia produces something like 7.5M net export-eligible barrels per day (net surplus), though this number is disputed in foreign policy circles. The “rule of thumb” number is 11M barrels per day produced and 3.5M barrels per day domestically consumed, but many experts question whether published numbers are accurate.