Managing Expectations and Advancing Reform: A Criteria-Based Approach to the HDP Nexus

This is the eighth chapter in a forthcoming e-book, entitled 'The Triple Humanitarian, Development and Peace Nexus: In Context and Everyday Perspective', edited by Marina Ferrero Baselga and Rodrigo Mena. Chapters will serialised on Global Policy over the coming months.

When I began my think tank work on the triple ‘Humanitarian-Development-Peace’ Nexus in 2019, the starting point was an obvious gap in debate and analysis: Three years after the World Humanitarian Summit, the Triple Nexus was still mostly an issue of theoretical discussion and Western capitol debates. But what about the “Triple Nexus in Practice” - as we called our research project at the Centre for Humanitarian Action (CHA)?

Five years later, in autumn 2024, we hosted a meeting of the German “Humanitarian-Development-Peace Community of Practice” at our office—a forum of around 40 donor and practitioner representatives. We invited Michael Köhler, former head of ECHO and current Grand Bargain Ambassador for the HDP Nexus, to share his perspective on where the Nexus stands globally. His opening remark captured the core challenge: he expressed surprise at encountering such a practice-focused forum in Germany, contrasting it with the broader international landscape, which he described as still dominated by a “Community of Theory.”

It’s worth acknowledging that over the past five years, discussions, analyses, and publications on HDP practice have expanded significantly beyond CHA’s contributions, accompanied by a growing number of HDP evaluations. However, the results have remained pretty much the same year after year. A look at, for example, about 70 evaluations on HDP programmes published has echoed lately (Morinière and Morrison-Métois 2023) what has also been the overall outcome of a few CHA evaluations on the matter: It is still evident that, in spite of some progress, HDP operational practice has been limited. In particular, peace elements are often poorly integrated, and the conceptional and practical HDP outline is still a matter of confusion, among others.

At the same time, with shrinking public budgets, aid-contesting narratives, and calls for efficiency gains and prioritisation goals feeding into a new dynamic, there is a new momentum for the HDP Nexus today in various international fora. This brings us back to a crucial question: from a practical perspective, what needs to be considered when (re)examining whether, where, and how a HDP approach can drive meaningful reform toward more effective aid programming and international cooperation?

When starting the HDP process, many aid actors have been sceptical in the light of a previous dual Humanitarian-Development Nexus and related Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development (LRRD) approaches that made very limited progress (Macrae and Harmer 2004; Otto and Weingärtner 2013; Kocks et al. 2018; Steets 2011). Some humanitarian organisations, like Doctors without Borders, also raised fundamental concerns at the WHS 2016 that the very political peace arena might undermine humanitarian principles of neutrality and impartiality (MSF 2016).

At the same time, aid agencies with mandates extending beyond humanitarian work were increasingly compelled to position themselves within the evolving discourse around the Triple Nexus—even though, historically, the peace component had played only a marginal role in their programming. However, for most multi-mandated organisations committed to addressing the root causes of poverty, maintaining strict neutrality is no longer a viable option. Today, this long-standing commitment is under increasing pressure, as most large-scale crises are deeply rooted in contexts of fragility, conflict, and war—reflected by the fact that around 80% of humanitarian aid is now directed to conflict-affected or fragile regions (Churruca Muguruza 2015; World Bank 2024). Besides, many multi-mandated organisations rely heavily on funding from government donors who actively promote the Triple Nexus agenda.

This mixed background resulted in at least three conceptions of the Triple Nexus which could be identified among most international actors, namely:

- only the latest buzzword in a repetitive debate,

- a dangerous agenda further blurring the lines of neutral and impartial humanitarian action with politicised approaches of development and security actors,

- a chance / a need to overcome siloed, ineffective concepts.

To clarify where the international “community of practitioners” stands in this regard, only a few survey results can be considered. These indicate substantial support for the overall approach – but even more cluelessness as to how to tackle it.

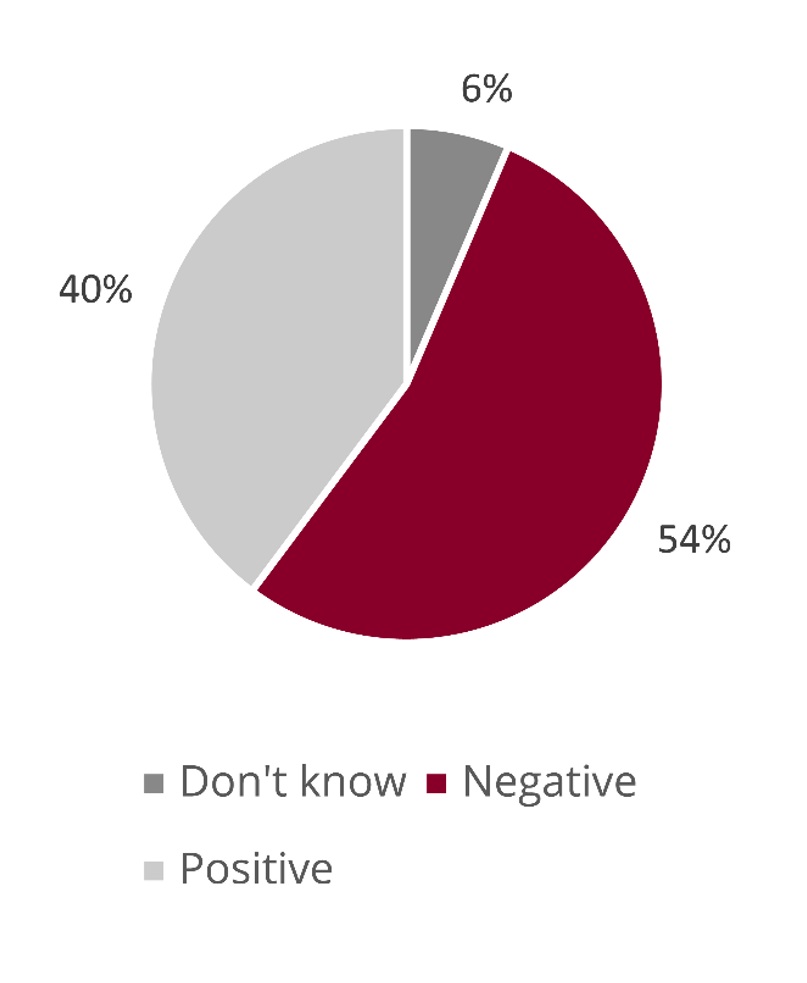

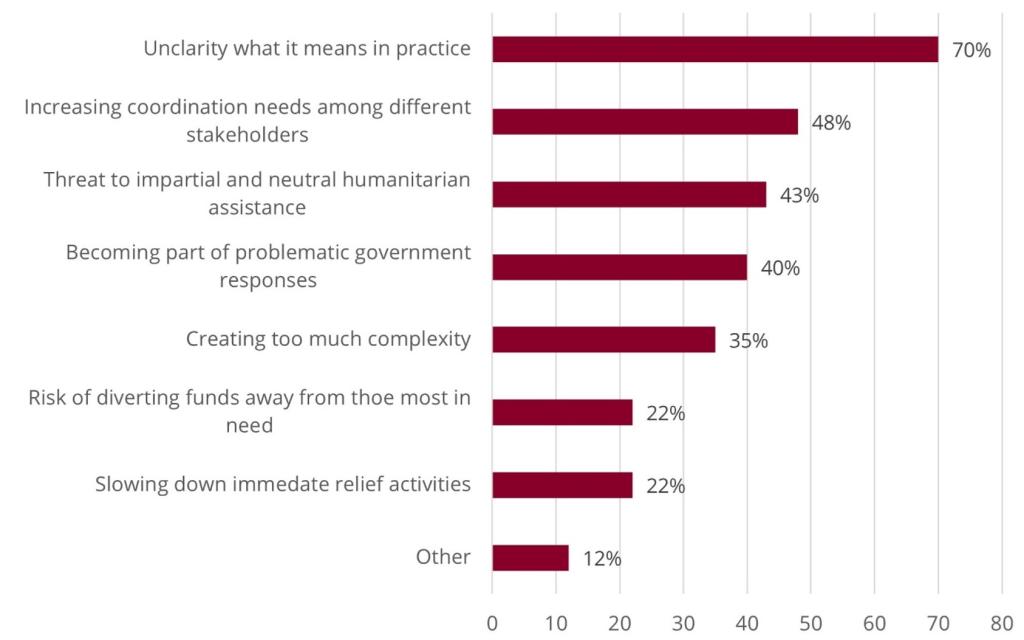

On the one hand surveys find a strong ask among practitioners that their employing organisations should expand their future peace engagements (graph 1). However, the same survey group argued that their own organisation is not well prepared for this (54%, graph 2). Even more seriously, an overall “unclarity what it means in practice” has been shared as by far the most important “key challenge” to implement a Triple Nexus approach (70% of respondents / graph 3).

1 Should your organisation expand its engagement in peace efforts in future programming? By organisation type (N=89); Source: Südhoff, Hövelmann, and Steinke 2020.

2 Preparedness of the respondents' organisation to engage in the Triple Nexus (positive vs. negative) (N=101); Source: Südhoff, Hövelmann, and Steinke 2020.

3 Challenges to the implementation of the Triple Nexus (N=101, multiple answers possible); Source: Südhoff, Hövelmann, and Steinke 2020.

As these surveys are a couple of years old, one might expect things to have changed. But by 2022 nearly 75% of the State of the Humanitarian System (SOHS) 2022 practitioner survey respondents felt their organisation was doing a ‘poor’ or only ‘fair’ job on the nexus. Research from 2023 showed that “there is ongoing confusion over what the nexus looks like in practice and how best to operationalise it” (ALNAP 2023) while this confusion is also linked to concerns regarding much-contested understandings of peace and its boundaries with security and stabilisation policies.

In short: Until today, 8 years after the WHS aid agencies can neither build on a consensus about the Triple Nexus theoretical concept, nor on practical, evidence-based experiences of a real Triple Nexus approach - while aid actors’ fundraising objectives lead in times of rapidly shrinking public aid budgets to further rising pressures to position in the HDP arena. This underlines the ongoing dilemma of a HDP nexus still being stuck as a largely theoretical concept. So, which approaches and analytical tools might help practitioners to overcome this deadlock, and what criteria for evidence-based decision making should they be based on?

Current approaches

Against the backdrop of the conceptual and practical challenges outlined above, aid actors engaging with the Triple Nexus—particularly its peace component—have generally adopted one or more of the following approaches:

- A conventional Dual Nexus approach plus relabelling already existing elements as a “peace component”.

- A more flexible Dual Nexus approach that takes regular shocks into account by integrating for example “crisis modifiers” into programming, and by adding conflict sensitivity and risk analysis components.

- A Triple Nexus Approach, including peace elements based on a broad peace definition (the “small P” of e.g. social cohesion, education, economic opportunities).

- A Triple Nexus Approach, including peacebuilding / conflict transformation elements or with peacebuilding as the core element of the aid programme (“big P”) (Böttcher and Wittkowsky 2021).

- A mix of the above – with great varieties within organisations and their engagements in various crises, depending often less on elaborated strategies but personal perceptions, leaders’ backgrounds or funding opportunities and usually focussing on pilot level engagements.

Amid this diversity, it seems fair to say that one consensus by involved actors today is the approach “local context counts”. This is, for obvious reasons, an appropriate perspective. It is another question, however, whether this provides any evidence-based guidance for criteria-driven decision-making to define which local context counts and in which way.

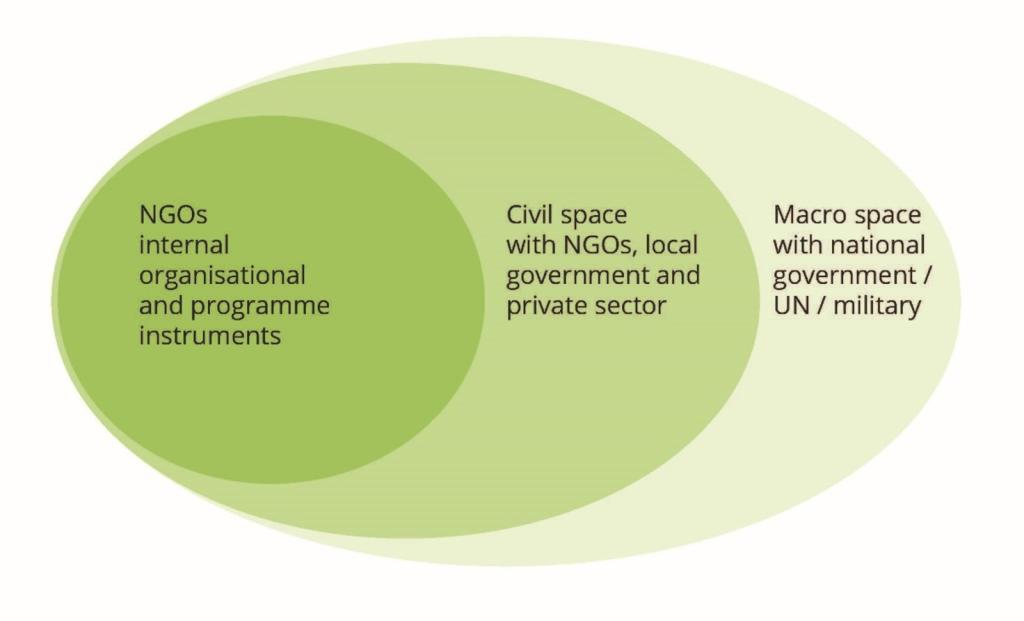

As this is a far more complex question than it might sound, analytical tools are essential for making accountable decisions. To this end, we have proposed an “Avocado” model to address the question of ‘where’ – specifically, what arenas and levels should be considered when assessing whether an HDP approach should be promoted in a given local context?

In our avocado (or CHAvocado model as we joked) three key areas are identified:

- The internal space of an aid actor (e.g., an international NGO), which we consider the core of the avocado and the starting point for assessing whether this core is fit for purpose.

- The civil space in a crisis context is the second layer from which the Nexus may extend. This space is often less politicized and less state-dominated, offering potential for community-level engagement.

- The outer layer of the avocado, usually the most contentious space, is the one most impacted by external factors. The core (i.e., the aid actor) has far less control over this layer, and here is the greatest risk for the avocado to get bruised. This level stands for the “macro space” occupied by often controversial actors, such as national governments (which are frequently conflict parties), UN actors (often seen as government-aligned or associated with conflict parties), and military forces.

4 CHAvocado Model; Source: Südhoff, Hövelmann, and Steinke 2020.

The main conclusion from the model is that, in order to determine the usefulness of an HDP approach within a given context, the very first step should be to analyse it systemically starting from the core. Is our organisation in the given context ready for this? Or is it already struggling with a working Humanitarian-Development Nexus if, for example, units cooperate poorly, or staff are not properly trained? Are other basics a given, such as ensuring that projects are based on substantial conflict analysis, as already required by the “Do No Harm” commitment? These questions may sound too simple to ask, but evaluations highlight that such basics are not a given in some big INGOs.

So, starting from the core, it is not a question of how to work in a HDP way on conflict, but to ask in the first place: Are we fit for purpose in this region to work in conflict, and to ensure we can engage around conflict doing no harm? If not, it may be necessary to first focus on a “Core approach” (Südhoff et al 2020) and consider developing an organizational Triple Nexus framework.

However, if these core conditions are met, engaging in the civil space might be an interesting opportunity to promote the HDP agenda - if crucial preconditions are in place. Some of these critical preconditions are surprisingly overlooked. Most importantly, can a local-level demand for international aid engagement in the peace arena be identified (as analysed in South Sudan, for example, by Quack and Südhoff 2020; Kemmerling 2024)? Or is this perceived as an international agenda that does more harm than good, as case studies on Mali suggested even before the coup (Steinke 2021; Tronc, Grace, and Nahikian 2019)?

This central question of local perspectives (see also final section) is reflected in key criteria to consider, such as whether capable and sufficiently impartial local partners are available for a substantial Triple Nexus engagement, and whether both international and local actors collectively bring the necessary peacebuilding expertise. If this is the case, a HDP engagement in the civil level might be a promising approach (Morinière and Morrison-Métois 2023).

At the same time, expectation management is key: Scope for progress in the community or civil space is usually limited. As a top leader of an INGO recently put it: “We made substantial progress on the local level. But how do we bring HDP and peace efforts from the community level to the regional or national one, where the dominant conflict dynamics often originate from?”

This doubt about the broader impact of successful HDP efforts on the local, civil level brings us to the outer layer of the avocado – the macro level. It highlights the dilemma that a HDP approach in most contexts would be most relevant on the level where it is most difficult to be implemented. For example, in Sahel crisis contexts, there are frequent calls for a comprehensive, macro-level approach that integrates humanitarian, development, and peace efforts to be truly effective. At the same time, key actors on the macro level whose engagement is essential – such as national governments, military, UN missions, external powers – are often discredited as conflict parties, in the Sahel and well beyond (ALNAP 2022; 2023; Hövelmann 2020). Given the rapidly escalating trends of conflict and fragility, a realistic approach will mean that a comprehensive HDP strategy at the 'macro space' or national level is more likely to be the exception than the rule in any given local context. This makes the local level and engagement the more important.

Local perspectives

It may sound obvious to put this perspective on HDP issues in practice at the centre, but the opposite is common practice. It is evident that, on the one hand, locally led aid and nexus challenges have emerged as top of the agenda in international debates. On the other hand, until lately both challenges have hardly been cross-referenced in conceptional debates and practical approaches with only rare exceptions (DuBois 2020).

In 2022 a case study on Venezuela migration crisis revealed that 60% of local aid actors had never heard about a HDP approach (Rey, Abellán, and Gómez 2022). The latest debates (Ministry of Foreign Affairs Denmark, IFRC, and USAID 2023) and publications highlight that this dimension of the HDP still being widely a “top-down approach” and request further research how a bottom-up approach could be pursued and the HDP decolonized (Müller-Koné et al. 2024; Meininghaus et al. 2024), while the agenda is not on the radar of ‘partner governments’ criticized OECD (OECD 2022).

Overall, this HDP status quo might appear bleak, but one could view the glass as half full. By adopting a realistic approach that focuses on local perspectives and evidence-based criteria to determine which HDP approach, if any, is appropriate or even feasible in a given context, we may find a key path forward—especially in these times of contested aid. Latest debates about prioritisation and politicisation of aid have highlighted how much aid actors are under pressure. If the sector fails to develop an effective and evidence-based HDP approach – one that includes clear criteria for when to pursue it and when to safeguard against the risks of doing more harm than good – other actors will step in and likely pursue it in a very different way.

The world’s top three aid donors have started this process on various levels: The EU’s Global Gateway initiative is on its way to create a mostly geopolitically focused nexus, which integrates efforts by deprioritizing development, humanitarian, and peace initiatives within a new foreign policy-driven agenda (Benlahsen, Ricci, and Rodier 2024). Germany has just launched a new humanitarian strategy focussing on security issues and prioritising crises “which are relevant for Europe” (Südhoff 2024). And the new Trump administration has made very clear that norms and values will play no role in its aid policies, if any such policy remains in place after the rapid dismantling of USAID. Who wants to promote a functionable, value-based and common good oriented HDP approach despite the challenges outlined above, needs to go for it now and fast.

Ralf Südhoff has been founding director of the Centre for Humanitarian Action (CHA) since January 2019. He focusses on German and European humanitarian action, humanitarian reform and the Grand Bargain, global food security, the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus, and the MENA region.

Photo by Ahmed akacha