AI, Sustainability and the Nature of Growth

Markus H.-P. Müller explores the unfounded perception that AI is fundamentally opposed to sustainability.

In this post, I argue that we should not see artificial intelligence (AI) and environmental sustainability as necessarily mutually incompatible. In reality, they are different approaches to the same problem: managing resources, both human and material. Past technological innovation has often increased demand for natural resources, but much will now depend on the nature of the growth that AI supports. Recent demographic trends may make it easier for AI and sustainability to co-exist.

Last year I wrote a post for the Global Policy Journal contrasting the different investor attitudes to AI and sustainability. My argument was that AI was seen as encouraging new and dynamic forms of economic activity and growth: it therefore had investment appeal. By contrast, sustainability was seen as imposing restrictions on activity and thus growth: this could (fairly or unfairly) foster investor scepticism. This narrative still appears to hold, and not just for investors. Many governments, increasingly focused on raising economic growth rates, are now reversing or delaying sustainability commitments, seeing this as one way to aid economic expansion.

In reality, AI and sustainability are and will remain interlinked. One example of this, currently much discussed, is the rising electrical power demands of data centres, due in part to the increased use of AI. These increased power demands will, in aggregate, have implications for overall global progress on decarbonization. Currently data centres account 1-1.5% of global final electricity demand (and data transmission for a similar amount) but rapid growth in large data centre demands (estimated by the IEA at 20-40% annually in recent years) is likely to lift this share higher. And the fact that data centres tend to be concentrated in certain regions, putting immediate pressure on existing power supply and networks has opened up a debate on how this power should be supplied, challenging some former shibboleths (e.g. recommissioning of old large nuclear reactor or construction of small new ones). This debate has been loudest in the U.S., but is also growing important in Europe: in Denmark, data centre usage is projected to rise six-fold by 2030 to account for 15% of total electricity use: in Ireland this share is already over 20%.

This energy debate reminds us that AI and sustainability are both, at root, about the management of global resources, human or physical. But current perceptions about how AI and sustainability do this are distinct. AI is seen as a way to improve the productivity of how we use resources – the flow. Sustainability is seen as a way of managing the stock of resources. This perceived distinction reflects the visible ways that AI is starting to affect our day-to-day lives – e.g. bolstering personal productivity via AI personal assistants. But other already-existing applications of AI (e.g. better power supply management across networks) already have implications both for the flow and stock of natural resources. As AI starts to have more profound implications for economic processes and products, its implications for sustainable resource management will grow.

So will AI eventually help sustainability or hinder it? Much will depend on the nature of the economic growth it engenders. In the past, major productivity-enhancing innovation (e.g. steam power, electrification) have boosted economic growth in part through allowing easier use of natural resource. This has been true not just of innovation of new technology (e.g. the steam engine) but also innovation within technologies designed to increase efficiency. Improving steam engine efficiency in the 18th and 19th centuries, for example, was successful in reducing coal consumption per unit of power output, but dramatically increased coal consumption overall as new uses were found for more efficient steam engines. This is the origin of the so-called Jevons paradox noted by the 19th century British economist of that name: greater efficiency can increase overall use, not reduce it.

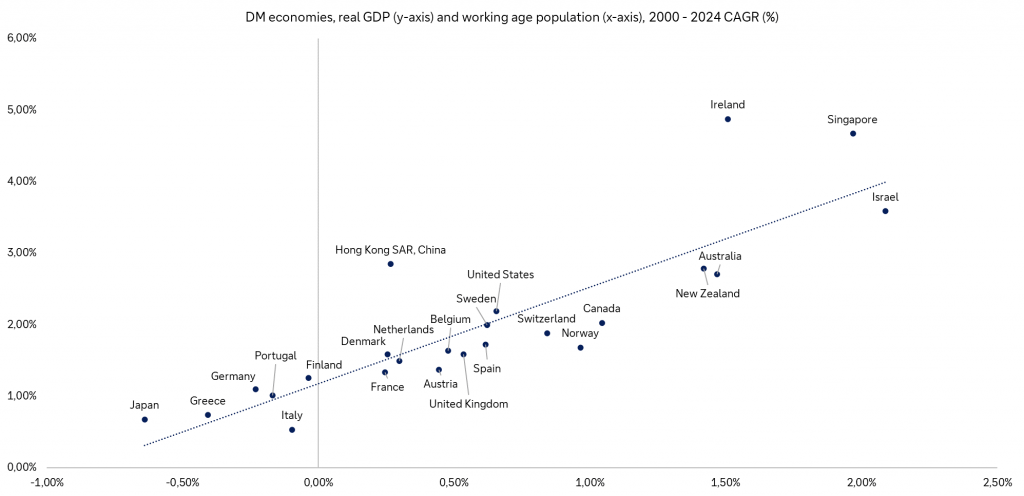

What could be different this time? Can AI increase productivity in a way that results in both higher economic growth and lower resource usage? We start in an interesting place: we are living in an age of slowing population growth (or even contraction) in many economies. As Figure 1 shows, the overall trend in population growth has been continuously sharply down and at some point in the future global population will start to fall. We appear to have reached a point where further increases in economic output are not now accompanied by sharp population increases, as food or other scarcity pressures are removed. In fact, the reverse seems to be the case: wealthy economies have particularly low, and falling, birth rates. This means that if AI-driven economic growth results in higher overall resource consumption, at least the global effects of this will not be amplified by the usual accompanying growth in population. However, it also means attempts to increase growth face an uphill battle: countries with slowly-growing or declining working age populations appear to expand more slowly.

Source: Bloomberg L.P., World Bank, Deutsche Bank AG. Data as of January 29, 2025.

I accept that we may be in a state of “pessimism aversion” on AI generally: we are not facing up to potentially major problems ahead. But I also understand why, in a period of historically low economic growth, there is also an obvious hunger for apparently easily-deployable ways to increase economic momentum. I think that a remodelling of the global trade order, which has been seen as a primary source of economic growth for several decades, will therefore increase the appetite for AI, not reduce it. AI can have a beneficial impact on how we live and its likely ability to help generate new products, processes and policies could offer multiple ways to speed up the sustainability transition. But we need to make sure this is a two-way street: AI already impacts decisions on sustainability, but sustainability should also have an influence on AI.

The current focus on supporting technology and output, notably in the U.S., has already resulted in the abandonment of some sustainability targets and projects. But AI, in itself, has not caused this: the problem is more an unfounded perception that it is fundamentally opposed to sustainability. In reality, they are different approaches to the same problem: managing scarce resources. AI aims manage resources in a more productive way to increase economic growth. The real question is the nature of this new economic growth. Will it, as often in the past, simply increase the pressure on natural resources? Or can AI, combined with demographic trends, help humans live in a less natural resource-intensive way? For sustainability’s sake, let’s hope for the latter outcome.

Markus is Global Head of the Chief Investment Office of Deutsche Bank Private Bank and in June 2022 he also took on the role of Chief Investment Officer Sustainability.

Photo by Google DeepMind