Development Economics: A Niche It's Not

Karl Muth suggests we should ask why studying the economics of the developing world is generally the preserve of graduate students?

This week, I undertake what has become an annual ritual: Thinking about how to teach Development Economics (Economics of Developing Countries ECON 326-0) at Northwestern University. This is a particularly weighty responsibility as Northwestern has only one undergraduate course on the Economics of Developing Countries and it’s a course I wrote and that I teach – in other words, if it doesn’t go well, it’s entirely my fault.

I wrote my Ph.D. at the London School of Economics where we had an entire department focused on International Development alongside a world-class Economics department with more than a few development economists (not to mention labour economists and macroeconomists and others who had an interest in the economics of developing countries). How do you fit it all into one course?

Well, to be short about it, the answer is that you don’t and can’t.

Now, Northwestern has wonderful resources for development economics at the graduate level, including bright graduate students at the masters and doctoral levels engaged in the study of how developing economies function, grow, and struggle (those interested in an advanced discussion should consider the ECON 560-0 workshop on Thursday afternoons). We also have the Center for the Study of Development Economics (est. 2011) and the Center for International Macroeconomics, which contributes regularly to debate and research on these topics.

However, I argue development economics is so vastly important to our understanding of our world, our civilization, and our history that reserving it mostly for graduate study is an unfortunate way to curate students’ learning. Our undergraduate economics curriculum includes courses like Comparative Economic Systems (ECON 305-0), Economics of Medical Care (ECON 307-0), and Advanced Topics in Macroeconomics (ECON 316-0) that often (logically and understandably) lead students to become interested in developing countries and their approaches to banks, monetary policy, regulation, and trade.

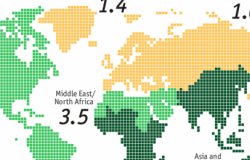

Development economics opened, for me, a different world and world view than I ever had experienced – or considered – before I studied it. Of seven billion inhabitants, 5.9 billion of our spaceship’s crew live in developing countries. Internationalised production (production in a country controlled by firms in another country, like American firm Apple’s iPhone made in China), grew from 4.5% of world industrial output in 1970 to 7% in 1995 and has accelerated from there (see cf. NBER working papers 5385, 6405, and 9293), much of this production occurring in developing countries. More of the goods and services we come in contact with today come from the developing world than ever before.

The concept that students should need to wait until they are studying – or have the luxury to study – at a more advanced level to learn about the systems that dictate and govern the lives of the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants strikes me as problematic. This is not a Northwestern problem or even an American problem, but a global issue: How do we take our best minds and aim them toward this important discipline that attempts to describe, if not solve, the problems that nearly six out of seven people face every day?

The first step, in my view, is to make development economics more visible to undergraduates. Each year, more students go to investment banks or funds where they are asked to contemplate how emerging markets function, go to treasury and desk functions where they are expected to understand the fundamentals that drive foreign exchange risk, and so on. By framing what happens in most of the world as a niche field of inquiry, we assign too little value to the topics involved and their utility, but also to the people who create, invent, manage, and struggle in these environments.

The “developing world” is not an untidy corner of our collective flat or a station on the underground where we’ve never bothered to check out the local pub. The developing world is our world – the vast majority of our world’s activity, area, culture, and people – and also our future. To not learn about developing economies and how they work is to be apathetic about their problems, affirmatively ignorant of our shared history, and tragically tardy in noticing these economies' importance.

I’m still learning, and we still – collectively – have much to learn. But it would be a terrible oversight, and unfairly selfish, to not help teach a bit of what we’ve learnt already; that’s what I do every spring. For those in ECON 326, see you on Mondays.