Imagining a Davos For the Many that was Actually Serious About Climate Change

Peter Bloom on what Davos might look like if it was serious about addressing climate change.

From the moment world leaders claiming to want to fight climate change arrived in private jets, the 2019 World Economic Forum in Davos attracted controversy. With global inequality growing and the threat of environmental destruction looming ever larger, the jets are getting larger and more expensive. The director of one private charter company says surging demand for his planes is partly down to “business rivals not wanting to be seen to be outdone by one another”.

This contradiction between rhetoric and action goes far beyond the use of private aircraft. It reveals the broader problems of allowing billionaires to not only control a disproportionate amount of the world’s wealth but also shape its political and economic agenda. While recognising the need for change, their solutions will almost always lead to a defence of the status quo from which they profit so handsomely.

Davos is just the tip of the iceberg of the more pervasive problem of “charitable billionaires”. On the surface, it would appear that having “the 1%” direct their wealth toward worthy causes is both laudatory and necessary. But such philanthrocapitalism promotes market-friendly policies and devalues the ability of democratic governments to provide social welfare or meet the needs of their citizens. As one critic noted:

the problems capitalist philanthropists claim to be solving are rooted in the same economic system that allows them to generate such enormous wealth in the first place.

An obvious answer may then be to simply dismiss the World Economic Forum and Davos altogether. Stopgap solutions such as seeking to address economic insecurity through employee “mindfulness and well-being” could be mocked, at best.

An alternative and sustainable Davos?

However, the ethos of Davos still has much to offer. It represents an effort to bring together global leaders and influencers to address problems that go beyond national borders. If anything, it would appear that we need more of these trans-national spaces for discussing technological innovation and social transformation.

For Davos to truly be effective though, it must stop serving as a space for elites to defend their status and power. It must no longer be a forum, for instance, for CEOs like Tim Cook of Apple to defend his company and his executive allies from the legitimate “big tech backlash”. Rather, it should be an opportunity to force billionaires to invest in ambitious progressive solutions for solving the very problems they are primarily responsible for causing.

Climate change is a crucial place to start. At the moment, the most that pro-environmental voices such as New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern can do is plead with elites to “get on the right side of history and embrace ‘guardianship’ of the earth”. Alternatively, Davos could be used to promote a more ambitious green agenda and directly challenge the power of the billionaire class and the politicians who continue to prop them up.

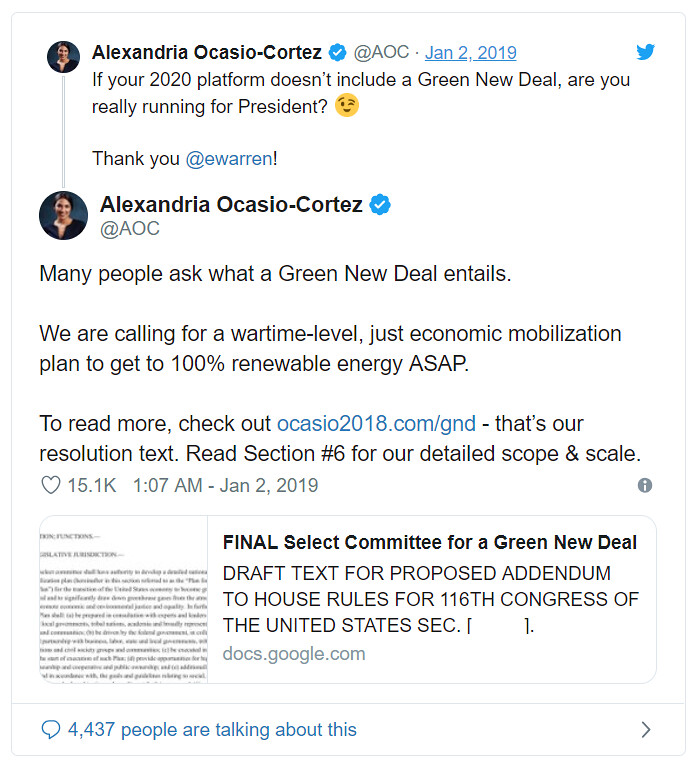

Leading up to Davos, US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez made headlines by calling for a “Green New Deal”. It proposes to have the US become a global leader in “decarbonising” its economy within ten years. Further, it will achieve these aims through massive public investment, a federal jobs guarantee, and a dramatic increase in the taxing of high income. The growing public support for this plan has also been a platform for progressive lawmakers to question the huge US military budget and tax cuts. Why, they ask, are war and wealth being prioritised over the housing, healthcare or the environment?

This is a good beginning. Yet it would benefit from having the support of global movements and the capital of global elites. In an alternative world, Davos could be just such a venue for an international commitment to innovation and progressive change. Rather than just having countries fight to tax their richest citizens and corporations, they could also mandate that they have to invest a percentage of their profits in the ideas and agenda proposed by leading experts and activists around the world every year. In this case, it would be for helping to fund countries and communities to put in place a “green new deal”.

The roots of such an alternative are already growing in events like the “World Social Forum” which is an attempt to bring together community and political leaders with leading thinkers to imagine a different “world” to the corporate-friendly one supported by the World Economic Forum. Critically, it advocates “glocal” solutions, customised to local conditions. Davos, in this regard, could be a yearly corrective where those most affected by elite policies could put forward the specific solutions for them to rectify it.

For this to happen it would mean transforming the very ethos of Davos from one of “idea sharing” to that of democratic accountability and justice. It entails delinking social value and influence from economic wealth and the political influence it buys. Instead, Davos could be an annual opportunity for experts and “the people” to propose the best and most cutting edge ideas for redistributing this wealth to where it is truly needed and can do the most good. Scientists warn that we have only 12 years potentially left to avert a “climate change catastrophe”. It is why we need to create an alternative Davos “for the many, not the few” as soon as possible.

Peter Bloom, Senior Lecturer in Organisation Studies, Department of People and Organisation, The Open University.

This first appeared at: