Trafficking to the Gulf States

This is part of a forthcoming Global Policy e-book on modern slavery. Contributions from leading experts highlighting practical and theoretical issues surrounding the persistence of slavery, human trafficking and forced labour are being serialised here over the coming months.

Abuses of migrant workers in the Gulf States have been documented over the years by numerous international organizations and news outlets. The mechanism through which migrant workers are recruited, transported and subjected to exploitation has been closely linked to the kafala system widely practiced in the region. This essay examines the kafala system and its role in the exploitation of migrant workers who are routinely subjected to false promises, isolation, coercion and exploitation, and argues that these abuses are tantamount to human trafficking.

Many migrants in the Gulf States work in unskilled, 3D (dirty, dangerous and demeaning) jobs across different sectors where they often find themselves subjected to various forms of exploitation. Abuses appear to be particularly egregious in the construction and domestic service industries where men and women experience harsh working and unhygienic living conditions, non-payment of salary, and retention of passports. Employers control not only the work, residence and salary of migrant workers, but also their ability to leave a job or the country. Domestic workers are especially at risk. They are frequently prohibited from leaving their employers’ homes, treated as commodities, and subjected to emotional, physical and sexual abuse or forced into prostitution.

Patterns in Receiving and Sending Countries

Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates comprise the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf, also known as the Gulf Cooperation Council, or GCC States. The discovery of oil in the region resulted in these countries becoming among the wealthiest in the world, all scoring very high on the 2022 United Nations Human Development Index. The region has also witnessed a rapid increase in population, from 4 million in 1950 to nearly 60 million today. This demographic change did not take place primarily due to an increase in birth rates but through the importation of foreign workers, resulting in immigrants comprising 51% of the GCC’s population in 2019.

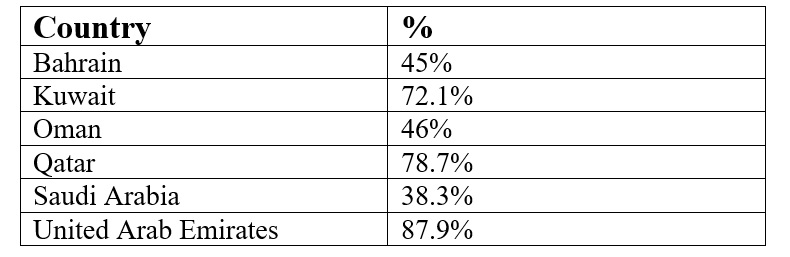

According to Philippe Fargues, the relatively small populations, immense wealth, and booming construction developments have created a demand for foreign workers and, to a large degree, explains the international migration flows to this region. According to the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), there were 35 million migrants in 2019 working in the GCC countries, and Jordan and Lebanon. Almost a third of these were women. Foreign nationals as a percentage of the GCC labor force (2019) varies from a low of 38.9% in Saudi Arabia, to a high of almost 88% in the United Arab Emirates (see Table 1).

Table 1: Foreign nationals as a Percentage of GCC Labor Force (2019)

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; International Migrant Stock (2019) Country Profiles

Laborers migrate from some of the poorest countries in the world in South Asia and parts of Africa, including Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. Driven by crushing poverty and high unemployment in source countries, and the discovery of oil in the Gulf States in the 1960’s, the first wave of unskilled foreign laborers came to the GCC countries to work on large construction projects. Immigration increased into the 1970’s. Male workers were followed by women who found employment as domestic workers. The number of domestic workers rapidly increased in the region. The International Trade Union Confederation estimates that 2.1 million women or more are at risk of exploitation through their employment in households across the GCC countries.

Human Trafficking, Worker Abuse, and the Kafala System

The GCC countries needed to create a balance between economic growth and the need for foreign workers on the one hand, while managing their fear of permanent settlement of non-Arab and non-Muslim foreign workers and their influence on cultural identity on the other. This was accomplished through the kafala, an immigration system characterized by tight security, rotation, and restrictions on workers’ mobility.

The kafala, an employer-driven sponsorship system, can be found in the GCC countries, Lebanon and Jordan. It regulates the relationship between the sponsor or host (kafeel) or employer and the migrant workers he employs. The system originated as a form of hospitality with the sponsor guaranteeing responsibility for the migrant’s visit, safety, and protection. Today, the kafala system has transformed into a system of structural dependence giving the kafeel significant legal and economic power over the migrant worker. The worker’s dependency on the kafeel is what creates vulnerability and facilitates abuse and exploitation.

This unequal power dynamic between a kafeel and a migrant worker may lead to abusive, slavery-like situations. Abuses of the sponsorship system entail elements of “servitude, slavery, and practices similar to slavery” that commensurate to human trafficking. Radhika Kanchana argues the kafala system is an “instrument to control the foreign worker, with the primary objective to balance the demand for foreign labour and to retain maximum advantage for the national population”. Furthermore, she argues, slavery was practiced in the Gulf region until the twentieth century, perhaps laying the groundwork for a high tolerance level among the local population to forced labor. According to the Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain, the kafala system has been described as “… a deeply seeded structural system that causes, permits, and in some cases encourages violence towards migrant workers.”

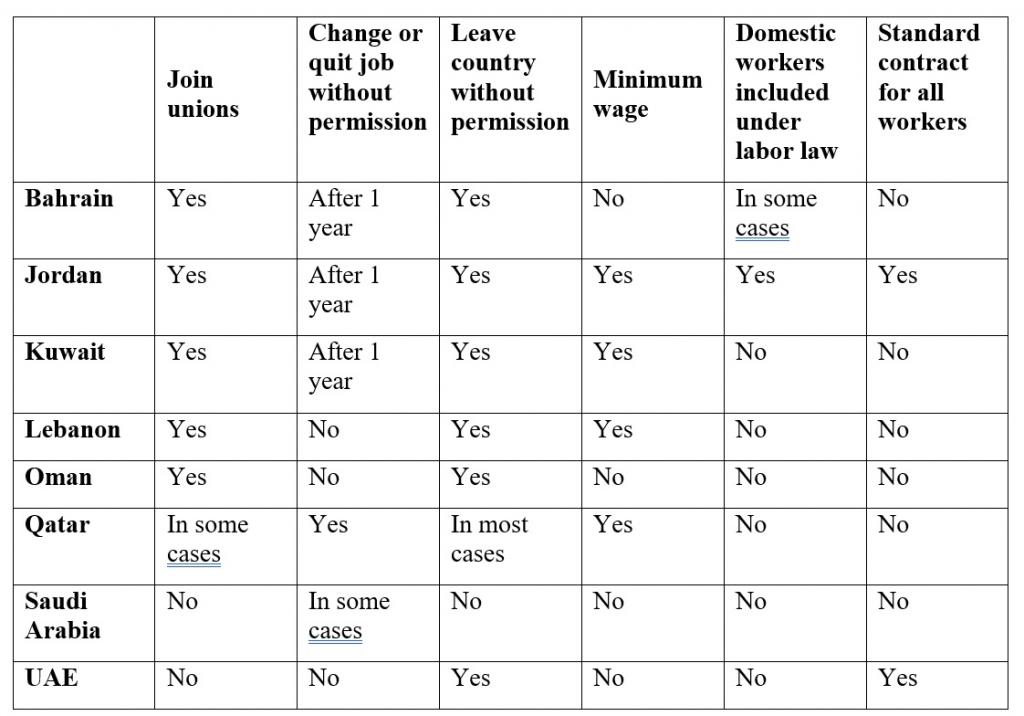

In some countries, an employee is barred from seeking other employment or leaving the country without the permission of the original sponsor. Workers who attempt to flee abusive employers are considered “absconders” - illegals – and may be detained indefinitely or deported at their own expense. In a 2021 overview of migrant worker rights prepared by the Council on Foreign Relations, access to labor unions, freedom to quit or leave the country without employer’s permission, minimum wage, and standard contracts, as well as inclusion of domestic workers under the labor law is compared across the kafala countries (Table 2). While most countries allow workers to join unions and leave the country without the employer’s permission, fewer kafala countries provide standard contracts to all workers or offer equal protection to domestic workers under labor laws.

Table 2 Foreign Worker Rights by Host Country 2021

Labor exploitation and human trafficking have been long documented in the Gulf region by the U.S. Department of State, international organizations such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Human Rights Watch, the International Organization for Migration, the International Labour Organization, the International Trade Union Confederation and international media (Washington Post, Guardian). The restrictive conditions under the kafala system in the Middle East and Gulf States is a major contributing factor to the trafficking and exploitation of foreign workers in the region. For example, due to their initial financial investment in the recruitment and importation of foreign workers, employers are often anxious to recoup their investment, leading to a situation in which kafeel are hesitant to release workers until the initial investment is recuperated. Once this investment has been recuperated, or in order to bypass legal channels and avoid costs altogether, kafeel are turning to illicit practices involving buying and selling domestic servants online or through apps. Disappearing from the radar, the underground sale of domestic servants puts them at a heightened risk of abuse or harm as their location and status become intractable to the authorities.

Let us refer to the world’s most widely used definition of human trafficking, as specified in the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, which includes the following three elements : (1) an act (recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons), (2) the means (threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person), (3) for the purpose of exploitation, which includes, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

Under the kafala system, deception in recruitment begin s when workers pay exorbitant (and illegal) fees to recruitment agencies in their home countries. There they often sign contracts in their home countries only to find that the contract has been drawn up in a foreign language which the worker cannot read, or is destroyed upon arrival in the destination country. In some cases, contract substitution occurs whereby two contracts have been drawn up – one for the worker and an official one for the employer. Workers often incur large debts to pay the recruitment fees . Coercion and exploitation follows upon arrival in the destination country. Isolation and often coercion (physical, psychological or economic) are used to keep foreign workers in labor camps or locked in the homes of their employers. Deception follows. At their place of employment, which may be different than what was promised during recruitment in their home countries, workers’ passports are taken from them, and they are often forced to work for a salary far less than what was promised. Workers are often dependent upon their employers for shelter, clothing, food, medical care and transportation (multiple dependencies on an employer is an indicator of human trafficking), and may be subjected to physical and sexual abuse.

Workers are exposed to exploitative and sometimes dangerous working conditions including excessively long hours, working in the sweltering heat, limited periods of rest, rationed food, low (or no) pay, verbal and physical abuse by employers (Human Rights Watch, 2007; Khan and Harroff-Tavel, 2011; Bajracharya and Sijapati, 2012; Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain, 2014). Domestic workers are often kept isolated in the homes and subjected to physical and sexual abus e, while construction workers are forced to reside in labor camps on the outskirts of cities, often in crowded and unsanitary conditions characterized by a lack of electricity and clean running water. One study of human trafficking in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region found that all participants of the study had their identity documents withheld, almost 90% reported confinement to the place of employment, three quarters had their wages withheld. Over 70% experienced psychological abuse, more than 60% of migrants in the study suffered physical abuse, excessive working hours (52%), and deprivation of food and drink (48%). The situation appears to be particularly egregious in Qatar, where media has reported thousands of deaths among construction workers over the last years building the infrastructure in the country for the 2022 FIFA World Soccer Cup.

Reforms and the Way Forward

Comprehensive reforms by different stakeholders in both sending and receiving countries are necessary to ensure the protection of foreign workers in the Gulf States. The final section of this essay introduces several measures that have already been implemented in select countries that could serve as positive examples for the Gulf States and identifies the more ambitious reform proposals to address the current human trafficking and exploitation of migrant workers crisis.

Sending Countries

Specialised Departments for Overseas Foreign Workers, similar to the one in the Philippines, should be established within relevant ministries (e.g. Labor, Foreign Affairs) in all sending countries. This would enable a more efficient use of resources allocated to protecting migrating workers which are currently spread across different government institutions. The main task of such a governing body, following the Filipino model, would be to “formulate, plan, coordinate, promote, administer, and implement policies, and undertake systems for regulating, managing, and monitoring the overseas employment” of migrating workers, as well as to reintegrate returning workers and welcome incoming migrants.

In sending countries, or countries of origin, the accessibility of information about workers’ rights, labor laws, and relevant social practices in destination countries to foreign domestic workers must be improved. Pre-departure and post-arrival training, similar to that offered in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Nepal, should be provided to all migrants, and especially domestic workers. The beneficiaries of the training would learn about the location, inquiry procedures, and services provided by their Embassy making it easier to seek assistance in situations of abuse. In order to implement such programming, embassies of sending countries must work closely with human rights-based non-governmental organizations in receiving countries to integrate relevant information provision as part of the migration process and augment the avenues through which their citizens can reach out to seek protection.

Between Sending and Receiving Countries

Bilateral agreements specifying the rights and obligations of workers should be signed (and respected) between sending and receiving countries. Joint labor migration committees and data-sharing between sending and receiving countries could facilitate protection of migrant workers. This step has been taken by the Governments of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Uganda which have bilaterally agreed on a standard contract to protect the thousands of Ugandan women employed in the Kingdom as domestic workers.

Receiving Countries

Essential in destination countries is a National Referral Mechanism (NRM or equivalent mechanism) – a central body which ensures coordination between agencies working on identifying victims of human trafficking and directing them to the right resources. The NRM liaises with service providers and shelters, as well as monitors the flow of cases. This framework has been widely adopted in Western Europe, as well as the UAE and, since recently, in Saudi Arabia.

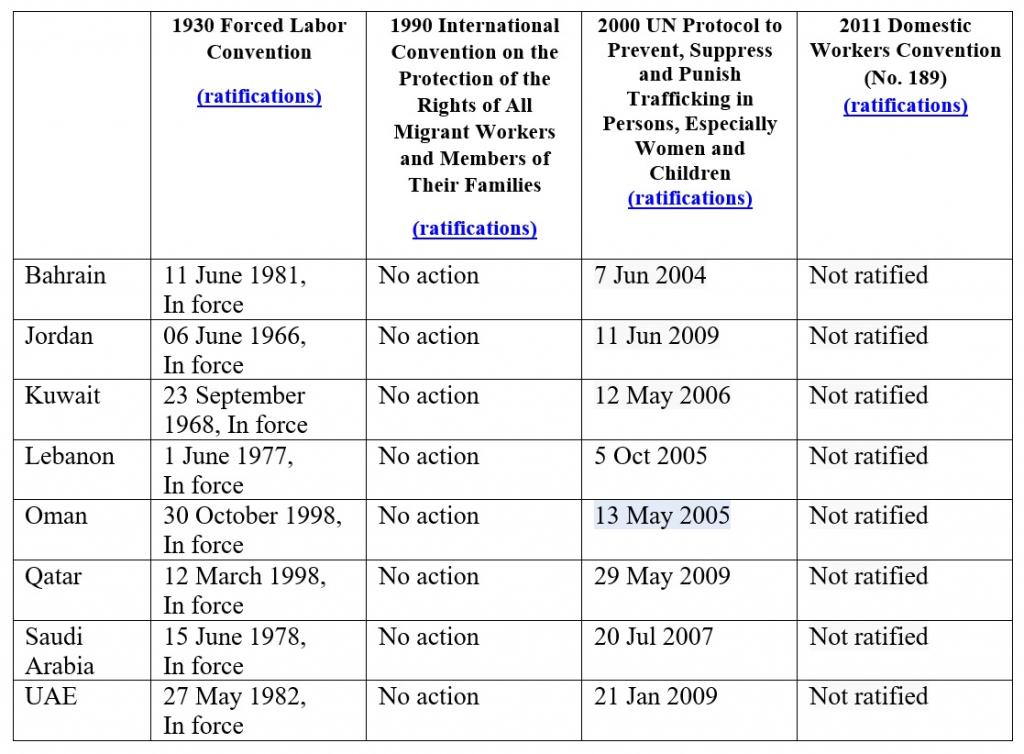

While ad-hoc measures implemented in the GCC in recent years have defined the region’s aspirational direction towards greater protection of the migrant population, systematic reforms are still needed to address the exploitation of migrant workers under the kafala system. On the most basic level, a number of international instruments were developed to protect individuals from forced labor and human trafficking. These include the 1930 Forced Labour Convention, the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, and the 2000 UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the 2011 Domestic Workers Convention. While all of the countries where the kafala system is practiced have ratified the Forced Labour Convention and Human Trafficking Protocol, not a single county has ratified the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families or the 2011 Domestic Workers Convention (see Table 3 below).

Table 3 Status of International Instruments in Force in Kafala countries

Despite years of international pressure from governments and human rights groups to abolish or reform the kafala system, GCC countries, Lebanon and Jordan are slow to introduce change. On the national legislation level, all kafala countries must ensure the following:

- All labor rights identified in Table 2 must be codified into the national law. Further, labor laws must regulate the maximum number of hours a laborer may work, specify minimum rest times.

- Ensure that workers have a legal right and material ability to litigate complaints against their employer in court. At a minimum, this would require that filing a complaint does not require payment on the part of the worker and translation services are freely available. Deportation must be prohibited if a complaint has been filed or an appeal is ongoing.

- Governments must actively investigate and shut down mala fide recruitment agencies that are suspected to deceive perspective workers.

- Financial compensation to (the families of) the worker must be made available to those injured or who die on the job while in the receiving countries.

- Regular risk assessments and monitoring of at-risk industries (e.g. agriculture, construction and domestic work) must be conducted by labor inspectors.

- Discriminatory attitudes towards (non-Muslim) foreign workers must be addressed through educational interventions in schools or awareness campaigns for the public.

Protection of migrant workers can only be realized if adequate laws and policies exist and there is political will and technical and resource capacity to enforce them. Enforcement remains a major challenge as the kafala countries routinely fail to deliver penalties to offending employers in the form of fines, closure of businesses or license withdrawal.

Stakeholders other than national governments can also contribute to the protection of migrant workers in the kafala countries. For example, multinational construction firms can establish human-rights based guidelines and ensure that local subcontractors adhere to them. Banks can offer free of charge accounts for foreign workers along with monitoring systems that survey monthly salary deposits. Recruitment and placement agencies, in both sending and receiving countries, can alleviate the change levied on job seekers for their placement in receiving countries. Private businesses, as well as governments, can work to improve the often unsanitary and unsafe living conditions, especially in work camp residences.

Concluding Remarks

The abuses of the kafala system have led to a major migrant labor rights crisis in the Gulf States placing thousands of workers in situations of trafficking and slavery. An effective response to the power imbalance in the sponsor-employee relationship would require a series of integrated interventions targeting the many aspects of the migration process that disadvantage and endanger the migrant worker.

To start, sending countries must shut down and prosecute mala fide recruitment agencies charging exorbitant recruitment fees. The increased availability of information prior to departure through trainings can ensure that workers are aware of their obligations and rights, as well as the services provided by their embassy and NGOs in the receiving countries.

Secondly, the legislative environment in host countries needs to be strengthened and enforced. Labor rights must be enforced and extended to domestic workers to include adequate housing and health care, regular payment of salary, access to documents, limited working hours and free days. Private industry can play a major role in ensuring that a human-rights based approach is implemented in their working environment. Constant monitoring is necessary to ensure that worker’s rights are continuously protected. In cases of dispute or allegations of abuse, workers must be allowed to terminate the contract without a penalty. Rebuilding their lives and the lives of their families at home may mean that employers provide financial support to the families in the case of the injury or death of a migrant worker. Furthermore, recruitment agencies should cover the expenses of the kafeel whose investment may be at risk if a migrant worker leaves before the end of the contract, encouraging kafeel to release employees without fear of losing their investment.

Both sending and receiving countries are reliant upon the migration of workers to the GCC countries. A first step to the protection of vulnerable migrant workers is reform of the kafala system and enforcement of laws and regulations to protect their rights. Only the merging of these various approaches in both sending and receiving countries will guarantee a humane and effective campaign to eradicate forced labor, exploitation and human trafficking of migrant workers.

Alexis A. Aronowitz has worked as a research coordinator on human trafficking at the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute and as a consultant on projects on human trafficking for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women, the International Organization for Migration, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the International Victimology Institute Tilburg (University of Tilburg), Human Rights First, Management Systems International, Winrock International, and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. She has published extensively on the topic of human trafficking. Her book, Human Trafficking, Human Misery The Global Trade in Human Beings, was published by Praeger in 2009. Her second book, Human Trafficking: A Reference Handbook, was published in 2017.

Photo by Antony Trivet