Opening New Horizons: Bangladesh Joins the New Development Bank

This is the second in a new collection of commentaries from the Emerging Global Governance (EGG) Project on the New Development Bank's evolution. Browse the series here. Gregory T. Chin and Rifat D. Kamal argue that Bangladesh has major infrastructure financing needs, and Dhaka is willing to borrow in large amounts from external multilateral lenders.

Bangladesh became the first country to join the BRICS-led New Development Bank after its original members, on 28 September 2021. For the Bank, and its BRICS founding members, it had taken almost 6-years to make this move, after opening in Shanghai in December 2015.

Bangladesh acceded to the New Development Bank (NDB) just ahead of the UAE and Uruguay, and Egypt in December 2021.

NDB president Marcos Troyjo declared, “we are delighted to welcome Bangladesh, one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, into the NDB.” He added that the country was joining the year it was celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of its independence, an “important milestone”, and an “honour” for the Bank.

In joining the NDB, Bangladesh is opening new horizons and potentially important new financing channels for the country’s development. But it should not be missed that the addition of Bangladesh also broadens the base of borrowers and members for the Bank, which continues to aspire to be the premier multilateral development institution for the emerging economy countries.

Why Bangladesh Joined

How will membership in the NDB potentially benefit Bangladesh?

Finance minister AHM Mustafa Kamal said (September 2021) that Bangladesh’s membership in the Bank paves the “way for a new partnership” at a “momentous time” for the nation, and is an “important step forward” in meeting the development vision of the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina referred to the country joining the Bank as a ‘time-benefitting’ achievement that will open a new avenue of foreign financing for the country, and that it will play a supportive role in achieving the country’s development goals.

The Prime Minister and the finance minister are both speaking about the Bangladesh government’s “Vision 2041”, the programme running from 2021 to 2041 in which the country is striving to eradicate extreme poverty and achieve the status of an “Upper Middle Income Country” (UMIC) by 2030, and then the status of “High Income Country” (HIC) by 2041, at which poverty has been largely eliminated.

The finance minister said the government is “deeply committed” to elevating Bangladesh to the level of developed countries within the next twenty-years by improving economic and social standards in the country, and by realizing the Vision 2041, and the UN-led Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Finance minister Kamal emphasized that although the Bangladesh economy has been developing at a tremendous pace during the last decade, the country still needs a substantial amount of external financing to help sustain the national development initiatives.

Bangladesh crossed the thresholds for the World Bank’s definition of “lower middle-income country” (LMIC) in 2015. The country has achieved impressive development results in the recent decades, and gains in poverty reduction and improvements in social indicators, but there are still significant pockets of poverty. At the same time, Bangladesh’s national developmental challenges go beyond the “poverty alleviation” agenda of the traditional donors and the established MDBs. For Bangladesh, environmental and social challenges remain, as do major needs in infrastructure development (including energy infrastructure, digital infrastructure, health infrastructure). External donors who use only “low-income country” instruments such as “targeted poverty reduction” are not sufficient to meet Bangladesh’s developmental needs, if ever they were appropriate or enough, and that is debatable.

Similar to other countries in the South Asian region, Bangladesh has enormous gaps in physical infrastructure. As the fastest growing economy in South Asia, Bangladesh is putting considerable resources into developing its infrastructure, energy power, and communication networks, even while maintaining “steady monetary policy and fiscal discipline”, and “macroeconomic stability”.

However, Bangladesh faces two main infrastructural development challenges. The first is its geography, and the second is limited financial resources. Bangladesh is a low-lying riverine country with a coastline of 580 km along the northern littoral of the Bay of Bengal. Much of its territory is frequently flooded during the monsoon season. It is therefore extremely difficult and expensive to build modern transportation and communication networks across the country – and yet, it is essential to support national development. To be more specific, Md Shamsuddoha at the Center for Participatory Research and Development in Dhaka writes that, Bangladesh, as one of the most climate-vulnerable countries, requires substantial investments in climate-resilient infrastructure development.

But Bangladesh, either because of its limited fiscal capacity or because of its “fiscal discipline” and “steady monetary policy” as lauded by the IMF, does not have adequate financial resources, on its own, to fund its infrastructure goals, particularly at the rate that is needed. Nonetheless, the country’s investment needs have increased substantially as the country has been undergoing the shift from a rural-based agrarian economy toward a more urban-based manufacturing and service economy, and as the country strives to become a middle-income country. To fulfil these aspirations, Bangladesh requires much more capital investment in energy, infrastructure and communication networks. The government is looking to external partnerships, to share best practices, skills, expertise, and cash. According to Kamal, “membership in the NDB will give us a significant channel for that [external development financing].” Bangladesh officials are aware that the NDB, since its inception in late 2015, has provided about $30 billion in loans to member states for 70 different projects related to sustainable infrastructure and sustainable development more broadly. The NDB has also made a number of recent loans to support its members in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The NDB wrote that Bangladesh will have in the Bank a “new platform to foster cooperation in infrastructure and sustainable development with BRICS and upcoming new members.”

Kamal paid tribute to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Father of the Nation, and his dream to build a ‘Sonar Bangla’ (Golden Bangladesh), and he said that “we [Bangladesh government] look forward to working closely with NDB to build together a prosperous and equitable world for our next generation.”

How Bangladesh Joined

The NDB Board of Governors authorized the Bank to hold formal negotiations with prospective members in late 2020. After one initial round of negotiations with potential candidate countries, NDB staff continued the negotiations with Bangladesh, UAE, Uruguay, and Egypt, as the first group of countries to be admitted to the Bank.

There are some interesting regional and geopolitical wrinkles to the story of how and when Bangladesh joined the NDB. One of the dimensions is how India’s relations with Bangladesh, specifically India’s support for Bangladesh to join the NDB is a key element of the story. The point here is that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi invited Bangladesh to join the Bank at a virtual summit in December 2019, that Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina “responded positively”, and thereby set the country on the path to joining the Bank.

On 2 September 2021, the NDB announced it had initiated the membership expansion. According to the NDB president, Bangladesh was the first to deposit its instrument of accession, and “so officially, Bangladesh is now a full member of our institution.” Bangladesh has a subscribed capital of US$942 million (1.85 percent of the total), and it received 1.88 percent of exercisable votes in the Bank’s boards. To accommodate Bangladesh’s membership, the capital shares of each of the founding members was reduced, though the latter still hold a dominant 19.63 percent each (only slightly down from 20 percent each). UAE, Uruguay, and Egypt are also joining the NDB, but Bangladesh received assurances that its share of the votes will not go below 1 percent.

According to Bangladesh news sources, a finance ministry official said that of the country’s total share in the Bank (US$942 million), US$188.4 million is paid-in capital, while the rest US$753 million is authorized capital. The paid-in US$188.4 million will be deposited in seven instalments over seven years, and that subsequently, the country will be able to cover the remaining $753 million through the purchase of bonds of the NDB if it so desires. The seven-year period to pay the instalments and covering the remaining authorized capital through NDB bonds purchases, are procedural norms that apply to all of the NDB members and were established by the founding BRICS members.

Before starting the $188.4 million payment to the NDB, the government had to pass a law to this effect and complete other related domestic processes. With the start of the deposits of the instruments of accession (i.e. payments), Bangladesh joined the board meetings of the NDB, and became eligible for loans.

What It Means for the NDB

The main motivation for Bangladesh in joining the bank is as a borrower. However, Bangladesh, one of the top-ten fastest growing economies in the world (IMF 2017), has also become a particularly attractive borrower for the MDBs.

For the NDB, Bangladesh has the potential to be a major borrower from the Bank, considering its relatively large population, high growth rate, and major infrastructure and development needs. The addition of Bangladesh to the NDB membership means the inclusion of a sixth major emerging market customer for the aspiring Bank of emerging markets. It also further demonstrates, i.e. beyond the BRICS member-nations, that emerging nations can ‘stand on their own’, form their own new institutions for international governance and take collective action, and advance their new ideas, new approaches to sustained and sustainable development, anchored on sustainable infrastructure, and by mitigating the human sources of climate change and environmental damage.

In a Chinese media interview (CGTN), Troyjo underscored that “Bangladesh is the fastest growing country in the fastest growing region in the world, which is Asia. It’s [Bangladesh] one of the top thirty economies of the world, in terms of the gross domestic product measured in purchasing power parity terms, it has done a lot in terms of poverty alleviation, it has done a lot in terms of raising living standards, life expectancy at birth, it’s got huge infrastructure needs. So, I think a major important addition to the New Development Bank.”

To make the most of its scarce domestic capital, Bangladesh has emphasized ‘fast-tracking’ eight strategically important infrastructure and energy projects that support the nation’s continuous and rapid economic development (Government of Bangladesh, “Mega Projects in Transforming Infrastructure: New Dimension in Accelerating Growth”, Dhaka, 2016). In 2016, the government allocated more than US$2.3 billion in the national budget to move rapidly on the implementation of the fast-track “Megaprojects”. These “economy transforming projects” were projected to cost a total of around US$20.5 billion (another estimate was that these “Mega Projects” would cost of approximately US$ 43.6 billion).

The 2016 plan also relies on securing co-financing from MDBs for the priority infrastructure projects, and the original intention of the Bangladesh government was to ask the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, to some extent the Islamic Development Bank, as well as some other foreign bilateral ‘development partners’ (foreign bilateral lenders), including China within the Belt and Road Initiative, Japan’s International Cooperation Agency, and neighbouring India.

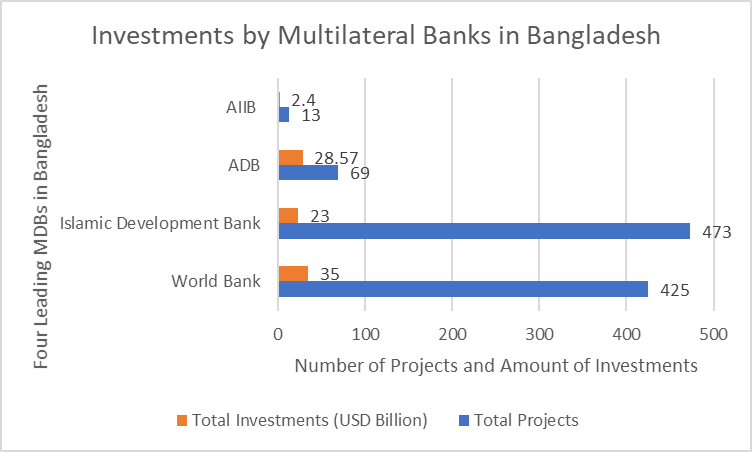

The country has received a large number of development loans from the World Bank, Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), and the Asian Development Bank over the last four decades. The World Bank has provided more than US$35 billion in support to Bangladesh since 1972, across 425 projects, and Bangladesh has the largest ongoing IDA program totalling over US$14.15 billion. However, the World Bank is not involved in any of the 13 infrastructure and energy power projects on the Megaprojects list. In 2012, the World Bank actually withdrew a US$1.2 billion IDA loan from one of the Megaprojects, the Padma Multipurpose Bridge, a construction project that started in 2009 and took until 2021 to complete. It ultimately carried a US$ 3.65 billion price tag and was self-funded by the Bangladesh government.

Despite not being involved in the Megaprojects, in the last three years the World Bank Group, through the Bank’s IDA loans (concessional financing with a 30-year terms, and a five-year grace period), has returned to making large loans to Bangladesh for infrastructure-related projects. In 2019, World Bank made a $100 million loan to the Bangladesh government on a water management project, “Municipal Water Supply and Sanitation Project”, to improve the control water of supply as well as sanitation and drainage in 30 municipalities (the loan has a 0.75 percent service charge and 1.25 percent interest, and the project also includes US$100 million financing from the AIIB, and US$ 9.35 million financing from the Bangladesh government). In June 2020, the World Bank approved US$500 million for the “Private Investment and Digital Entrepreneurship Project” that improves social and environmental standards in public and private economic zones and software technology parks in Bangladesh; develops the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Shilpa Nagar II in Mirsarai-Feni, a planned smart city zone. This includes installing road networks with stormwater drainage, solar-powered streetlights, climate-resistant water, sanitation, and power networks. The project has established Dhaka’s first digital entrepreneurship hub in the Janata Software Technology Park and constructed green buildings. Also in June 2020, the World Bank approved the US$295 million “Enhancing Digital Government and Economy Project”, a digital-infrastructure project that built an integrated, cloud-computing digital platform for all government agencies, with improved cyber security, and savings of US$200 million in public sector IT investments. The goal is to strengthen the country’s resiliency to respond to future crises, particularly the capacity to deliver critical public services to citizens and businesses.

In May 2021, the World Bank further approved a US$300 million “Resilience, Entrepreneurship and Livelihood Improvement Project” that aims to improve the living conditions of about 750,000 poor and vulnerable rural residents across 3,200 villages in 20 districts by building the capacity of village groups, and providing finance for climate-resilient infrastructure. Most recently, in February 2022, the World Bank approved US$300 million out of its concessional IDA funds to help Bangladesh strengthen its urban local government institutions to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and improve the country’s preparedness to future health shocks, benefitting about 40 million urban residents. The “Local Government COVID-19 Response and Recovery Project” supports 329 municipalities and 10 “city corporations” with bi-annual funding for critical urban services delivery of facilities and infrastructure, support for local economic recovery from COVID fallout, preparedness to climate impacts, disaster and future disease outbreaks. The financing is for labour-intensive public works projects implemented by urban local bodies. These projects range from installing community hand-washing stations and toilets to improvements in water supply, drainage, and sanitation in municipally-operated markets, burial grounds and public offices. Such projects in low-income areas, slums, and areas exposed to high disease outbreaks and disaster risks provide jobs for the urban poor and vulnerable people who often work in the informal sectors and have been most affected by the COVID-19 lockdowns.

The IsDB has lent more than US$23 billion in 473 projects since 1974, and Bangladesh is the largest recipient of IsDB Group financing, among its 57 member countries. The ADB has provided a total of US$28.57 billion of loans, grants, and technical assistance to Bangladesh since 1973, including cumulative loans and grants to Bangladesh worth US$17.12 billion. The IDB and ADB have each recently made loans to Bangladesh for infrastructure projects. For example, in 2021, the ADB provided a $200 million loan to Bangladesh to help improve the power grid in the country, to strengthen the efficiency and reliability of the electrical supply for over 150,000 rural households in Khulna Division, in southwestern Bangladesh. In 2021, the IsDB approved a comparatively smaller loan of US$36.4 million for the Inclusive and Integrated Sanitation and Hygiene Project in 10 priority towns in Bangladesh. Previously, in June 2018, the IsDB agreed to provide financing for a 22-year gas-fired power plant project in Bhola Island, Bangladesh, co-financed with the newly created AIIB in June 2018. The IDB’s contribution was a US$60 million Ijara facility with a 18-year ‘door to door tenor’ (the total period within which the total debt borrowed is to be paid back by the borrower to the lender).

Chart: MDB Investment in Bangladesh

Source: Chart by Rifat D. Kamal. Data from World Bank, ADB, AIIB, IsDB.

The ongoing investment by the World Bank, IDB, and ADB shows that Bangladesh has a long-established track-record of borrowing from the MDB family. However, it is also fair to point out that despite the increasing financing for infrastructure from the established MDBs, Bangladesh still has a lot of unmet infrastructure investment needs beyond its Megaprojects plan.

One of the newest members to the ‘MDB family, the AIIB, has helped to fill some of the gap. In the six years since the AIIB was launched, it has already approved Bangladesh for more than $2.4 billion in loans, for 14 projects and programmes, including 10 approved AIIB loans for infrastructure projects, and four recent COVID-19-related response programmes (as of February 2022). Bangladesh has proposed another five projects to the AIIB totalling about $1.6 billion.

Table: AIIB Infrastructure Projects in Bangladesh

|

Year |

Project Name |

Sector |

AIIB Loan |

Co-Financer/s (USD, million) |

National Contributions /Private Sponsors (USD, million) |

Implementing Agency/ies |

|

2021 |

Mymensingh Kewatkhali Bridge |

Transport |

USD260 million |

N/A |

Government of Bangladesh (GOB), $121.4 million |

Ministry of Roads, Transport and Bridges (MRTB), Department of Roads and Highways |

|

2020 |

Rural Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Human Capital Development Project |

Water |

UDS 200 million |

World Bank, $ 200.00 million |

GOB, $150.50 million |

Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) and Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) |

|

2020 |

Dhaka Sanitation Improvement |

Water |

USD170 million |

IDB, $ 170 million |

GOB, $ 143 million |

Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA) |

|

2020 |

Sylhet to Tamabil Road Upgrade |

Transport |

USD404 million |

N/A |

GOB, $180.5 million |

Roads and Highways Department |

|

2020 |

Dhaka and West Zone Transmission Grid Expansion |

Energy |

USD200 million |

ADB, $ 300 million, and People’s Republic of China Poverty Reduction & Regional Cooperation Fund, $ 0.75 million |

GOB, $ 249.25 million to this project |

Power Grid Company of Bangladesh (PGCB) |

|

2019 |

Municipal Water Supply and Sanitation Project |

Water |

USD100 million |

World Bank, $ 100 million |

GOB, $ 9.53million to this project |

Department of Public Health Engineering (GOB) |

|

2019 |

Power System Upgrade and Expansion |

Energy |

USD120 million |

N/A |

GOB, $ 46.39 million and PGCB, $10.21 million to this project |

Power Grid Corporation of Bangladesh (PGCB) |

|

2018 |

Bangladesh Bhola IPP |

Energy |

USD60 million |

Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), $ 60 million |

Nutan Bidyut (Bangladesh) Limited, $ 151. 9 million to this project. |

Shapoorji Pallonji Infrastructure Capital Company Private Limited through Nutan Bidyut Bangladesh Limited (NBBL) |

|

2017 |

Natural Gas Infrastructure and Efficiency Improvement |

Energy |

USD60 million |

ADB, $ 167 million |

GOB, $ 226 million to this project |

Bangladesh Gas Fields Company Limited (BGFCL) and Gas Transmission Company Limited (GTCL) |

|

2016 |

Distribution System Upgrade and Expansion |

Energy |

USD165 million |

N/A |

N/A |

Bangladesh Rural Electrification Board (BREB) and the Dhaka Electric Supply Company Limited (DESCO) |

Source: Table by Rifat D. Kamal. AIIB data

Although the AIIB ranks fourth as a source of multilateral development finance for Bangladesh, its investment is noteworthy because it is focused on infrastructure development, whereas the other three MDBs are spread across a variety of sectors, ranging from poverty alleviation, basic education, basic health, gender equity, and social protection.

From the perspective of the NDB, what can be interpreted is that the AIIB’s fast-growing infrastructure investment in Bangladesh, together with the recent infrastructure projects loans from the World Bank, ADB and IsDB indicate that Bangladesh has major infrastructure financing needs over the short-, medium- and longer-term, and that Dhaka is willing to borrow in large amounts for national infrastructure development from external multilateral lenders.

Clear and transparent information on the respective MDB lending commitments for Bangladesh, especially for infrastructure projects, or related information from the Bangladesh government, would actually provide some indication of Bangladesh’s potential future MDB-related borrowing for infrastructure, including from the NDB. So far, the only data that the authors have found in the public domain is the ADB’s statement that during 2021-2023, the ADB has committed to a “pipeline of 30 firm projects worth US$ 5.9 billion and 27 standby projects worth US$ 5.2 billion for Bangladesh.” The ADB has also committed to technical assistance programs for Bangladesh of about US$52 million (including co-financing) for 39 projects. Future research will delve into how much infrastructure financing is in these commitments, and in the commitments of the other MDBs.

For now, finance minister AHM Mustafa Kamal states that the government hopes that Bangladesh’s membership in the NDB will similarly “pave the way” for a new partnership on infrastructure investment at a critical juncture in Bangladesh’s “independent” development, and that Bangladesh joining will also benefit the NDB and its now ‘BRICS Plus’ membership.

Gregory T. Chin is Associate Professor of Political Economy in the Department of Politics at York University, Canada. He has published widely on the political economy of money and finance of China, Asia, the BRICS, and global governance. He is co-director of the Emerging Global Governance (EGG) Project, working in cooperation with Global Policy journal, and a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Institute at the Johns Hopkins University, School of Advanced International Studies. He is finishing a book manuscript on the internationalization of China's currency, the renminbi. Chin served previously in the Government of Canada (2000-2006) at the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, the Canadian International Development Agency, and the Canadian Embassy in Beijing.

Rifat D. Kamal is Assistant Professor at the University of Chittagong, Bangladesh, and she is a Doctoral Candidate in Political Science at York University, Canada, working on a doctoral thesis on the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank, and the political economy and international relations of Bangladesh, Egypt, and Indonesia.

Image: Photo by Ferdous Hasan from Pexels