The Stock Market Fetish

Branko Milanovic argues that the most recent turmoil in the stock market caused by Donald Trump’s ill-considered policy to impose tariffs on the entire world, has brought up one legitimate question: what is the correct attitude towards stock market declines and crashes?

This is a question being asked regardless of the chain of decisions and events that had brought the stock market recently down.

I can quite readily understand that the reaction of the capitalist class and the right-wing elite would be to be appalled by such declines. This is quite obvious from the think-tanks and the mainstream press. These are cataclysmic events—for them. Their opinions are guided by only two principles: to reduce own tax rates and to become richer through appreciation of capital they own. So it makes total sense that they should outraged by the declines in the stock market.

But the question is why should the left be against stock market declines? Not only that: prime facie all arguments are that the left should be in favor.

First, the stock market declines make wealth inequality less dramatic. This is empirically true; but it is also obvious from an analogy of opposite movements as when the recent booming stock market created outrageous capital gains among many plutocrats, including Elon Musk whose wealth rose from some $200 to $400 billions. This episode led many left-wing economists and Oxfam to graphically show how concentrated is global wealth by writing that a group of billionaires that would hardly fill a small bus owns as much wealth as the remaining 8 billion people in the world. But now the opposite movement is taking place. By analogy one would expect that the current declines in the stock market, which have in percentage terms affected more the wealthy, would be welcomed because they reduce wealth inequality. We would need, using the Oxfam imaginary, a bigger billionaire bus now.

Second, many recent left-wing policies advocate taxation of high-wealth individuals and the idea has even been floated that everybody whose wealth is above one billion should be taxed from their entire surplus (i.e. confiscation of all wealth above $1 billion). This lends additional support to the view that the stock market crashes are good. Instead of the state taxing away super wealthy capitalists, they themselves, by the operation of their own market, impose such self-inflicted pain.

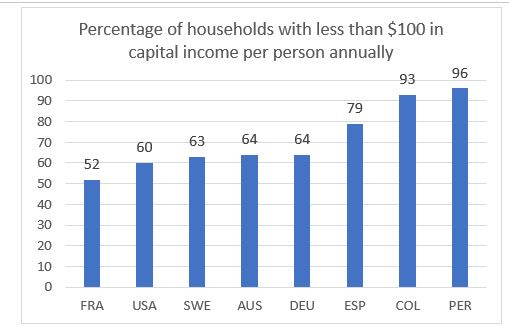

There is a third reason in favor of this view. Some 60% of Americans and likewise people in other advanced countries do not have any income from property (see the Figure below; the data are from national representative household surveys). Consequently only 40% of Americans receive any income from property, while in most developing countries that percentage is 3 to 7 percent (e.g. Peru 4%, Colombia 7% etc.). Around the world, if we were to add up all the people, we are unlikely to find that more than 10% (and likely as few as 5%) have any positive income from financial assets. Thus things that do not affect 90% to 95% of the world population are perhaps slightly exaggerated by the mainstream media whose owners and key customers are the rich? Quite possibly so.

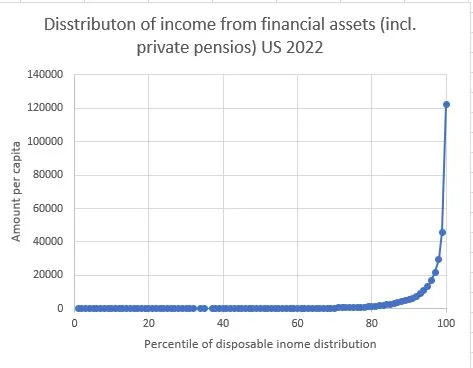

We can go further. Income from financial assets even among those 5-10% of the world population and 40% of Americans who receive it, is extraordinarily skewed toward the rich. Inequality of financial income is not like inequality of labor income. It is much higher. For example, labor income (before taxes) Gini in the United States is typically around 0.55; capital income Gini is above 0.9. The same is true for virtually every country in the world. Income from financial assets is like wealth: it is disproportionately received by the very top of the distribution. In the United States about 90% of all different financial instruments and assets are owned by only 10% of the richest Americans (see Ed Wolff, “A century of wealth in America”, Kuhn, Schularick and Steins, “Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949-2016”). Thus, saying that 40% of Americans have some income from financial assets is somewhat misleading because most of them have very little of it—and just a few receive the Gargantuan share. Which means that we should be even less worried if the stock market goes South.

So to summarize: there are several reasons for cheering up the decline in the stock market: it reduces wealth inequality by obliterating the wealth at the very top; it does not affect the incomes of most people (60% of Americans and 90-95% of the people in the world); and among those who are affected, it is la crème de la crème who lose the most and thus they are de facto taxed (a policy which otherwise is difficult to implement).

This is not what we observe in real life. The left does not bemoan the declines as much as the right, but is manifestly uncomfortable with them. There are two reasons that are generally adduced not to cheer things up.

The first argument says that while it is true that 60% of Americans do not have any income from capital some of them have assets like funded pension of the IRA or 401(k) type. These instruments can be accessed only under certain conditions (like age and emergencies) but during the accumulation stage they are not accessed and consequently they do not show in people’s annual income. But they will matter in the future. And people who have such instruments and are not millionaires do experience a decline in wealth when the stock market goes down. They do not experience any decline in income simply because (as we just said) they are not receiving anything from it now. They might experience lower income than expected only when they access these funds, perhaps in 3 or 5 or 30 years from now. If these assets remain at low value their future income would be less. But future stream of income is always the outcome of many contingencies and one of these contingencies is the performance of the stock market; no more can the people who have PAYG pensions be sure that when their retirement comes they would receive all that they have put in: a lot will depend on the situation on the labor market and whether there is enough current income to pay for pensions. Consequently, yes: if the stock market declines persist the owners of pension funds will receive less income in the future. (Further, when in any given year, we include income from private pensions as part of income from financial assets, the inclusion of pension funds makes no difference because those who receive them are already among the 40% who have non-zero financial asset income.)

The second argument is that the decline in the stock market precedes further retrenchment of investors because their expectations of future profits decline and consequently investments would be less and ultimately employment will be less too. Capitalists would engage into a kind of “capital strike”. But if it is true that any decline in wealth among the richest people is ultimately bound to lead to recession and lower employment, on what basis are we advocating taxation of the very wealthy individuals? Would not they, if taxed, cut their investments the same way that they cut their investments when the stock market misperforms? Consequently, to be consistent we should stop advocating higher tax rates on the wealthy because such taxes would have detrimental effect on future employment and wages of workers. This is exactly the right-wing argument, that the left seems to have tacitly accepted it—but holds it true only for stock market declines but not for taxes.

The third “defense” is perhaps the most intriguing. It has an ideological element. The fact that the importance of the stock market has become so disproportionate (compared to the role it plays in real life) and fetishized not only by the right and the center but even by the left shows a deeper inconsistency between the belief, maintained by some, of transcending capitalism and inability to think beyond the stock market. How is capitalism going to be transcended if one cannot transcend a bourse?; if one cannot imagine other systems of capitalism (let alone non-capitalism) that do not rely on the stock market for the allocation of investible funds? There is a capitalist model where the lending is done mostly by commercial banks to their clients. The stock market plays there a much smaller role. There is also a model of self- financing where companies do not distribute dividends but use the bulk of their profits to invest. This is what Chinese SOEs have been doing for the past 40 years. There is even have a third model where the state does lots of investing. Mariana Mazzuccato has shown that even in the United States many of the key technological advances (especially in ITs) owe their origin to government investments. So it is not true that a capitalist system has to imply a preponderant role for the stock market. Even more bizarre is to believe that capitalism is not a “natural”, but historical, system that needs to be transcended, and then to stumble upon the very first step when one is asked a question why should the left be worried about the price of rich people’s shares.

PS. This is how the distribution of income from financial assets (incl. private pensions) looks like in the US 2022.

59% of households have less than $100 per year per person. The median is $22 per year (i.e. <$2 per month). The top 1% has an average of $122,000 per capita per year.

So when you worry about the stock market you worry about this particular distribution. (Calculated from Luxembourg Incone Survey based on 2022 US Current Population Survey.)

PS2. Perhaps that I should have mentioned one obvious and well-known difference between the (fictitious) financial and real assets. The “loss” of wealth that occurs when the stock market goes does is simply due to our re-evaluation of future prospects. Nothing real has changed; only our expectations have. Now compare, say $1 billion of such fictitious losses with $1 billion worth of destruction of real assets: say an earthquake that destroys houses. In the latter case, rather obviously, there are real welfare effects: thousands of people would be homeless. This is a big difference.

This first appeared on Branko's Substack.

Photo by Kindel Media