Want to Challenge the Elite? Then first Understand What Makes Them Tick

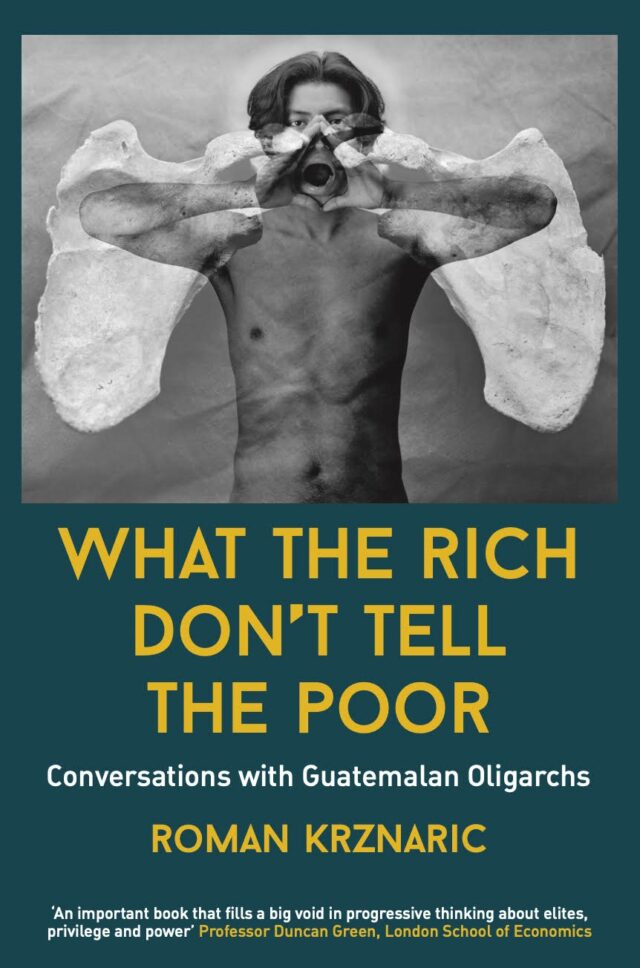

Understandably, perhaps, progressive researchers often prefer to try to understand the lives, challenges and struggles of the poor. Who wants to spend their time talking to sleazy fatcats? But if you want to change things, it’s often necessary to understand the people in charge. So I was very happy when public philosopher and political scientist Roman Krznaric sent over the manuscript for his latest book, What The Rich Don’t Tell The Poor: Conversations With Guatemalan Oligarchs. And fatcats don’t come much sleazier than the Guatemalan variety. It’s now published, and here he is summarizing its findings. It’s the follow up to his bestseller The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World, which I reviewed on FP2P back in 2020.

From the Russian oligarchs behind Putin to the digital oligarchs in Silicon Valley, the world’s economic elites have been growing in affluence and power. The number of global billionaires has leapt 30% during the pandemic to total some 2750 individuals, who together control more wealth than the planet’s poorest 4.6 billion people.

If we really want to challenge fundamental global inequalities it is essential that we develop a deeper understanding of oligarchs worldwide. Doing so offers vital strategic levers for confronting their power and privilege and for developing effective movements for change. But how much do we really know about what makes them tick?

In the early 2000s, I embarked on a seven-year investigation to find out. The results of what I learned appear in my new book, What The Rich Don’t Tell the Poor: Conversations With Guatemalan Oligarchs, in which members of Guatemala’s economic elite speak candidly in their own words on issues ranging from political violence and civil war to race, poverty and power.

In the early 2000s, I embarked on a seven-year investigation to find out. The results of what I learned appear in my new book, What The Rich Don’t Tell the Poor: Conversations With Guatemalan Oligarchs, in which members of Guatemala’s economic elite speak candidly in their own words on issues ranging from political violence and civil war to race, poverty and power.

Guatemala is well known not just for its extreme wealth inequalities but for having a ruling class or oligarchy comprising around fifty families of European descent who have maintained economic and political dominance since colonial times. Having worked with Indigenous Mayan communities on human rights, I realised that I had heard the voices of those who were oppressed and brutalised by poverty and violence, but almost nothing from the elites whose power upheld the system. So I was determined to speak to the oligarchs directly as part of my PhD research, on which the book is based.

But it was far from easy. Putting on a smart suit and carrying an elaborate letter of introduction from a foreign university helped me get the phone numbers of a few key business leaders from the British Embassy. I was then able to take advantage of the nature of economic elites: everybody knows each other, so once I had established trust with one interviewee it became easier to access another. I’ve no doubt that being a white European man also helped. Although I was officially researching the role of the business sector in the peace negotiations to end the country’s thirty-six-year civil war, in which over 200,000 mostly Indigenous Mayans were killed, I was also trying to investigate their support for the country’s brutal military during the war and find out all I could about how their power really worked in practice – with a view to discovering ways of challenging it.

Along the way I met people like the aristocratic businessman Manuel Ayau Cordón, who has since died. He passed me his business card as we sat in his office in Guatemala City, jokingly explaining how a foreign diplomat recently accused him in public of being an ‘arch typical far-right Latin libertarian oligarch’. Just for fun, he said, he had some business cards printed displaying this title. He then told me, in all seriousness, ‘I am leader of what they would call the ideological right.’

It was through such encounters that I tried to understand the worldview of the oligarchs – their motives, fears, hopes and vulnerabilities. While I recognise that every country and context is unique, I hope that what I learned in Guatemala may be of use to activists, researchers and changemakers in both the Global North and South who are committed to eroding the power of economic elites. Here are three broad insights I gained.

1. The oligarchy’s power is partly based on hollow threats

Economic elites often use the threat of capital flight to prevent governments from imposing higher taxes or other limits on their wealth. I discovered that – at least in the case of Guatemala – this is frequently an empty threat. Several business leaders I spoke with admitted that they had managed to thwart attempts to increase taxes or the minimum wage by telling government leaders that they would close their businesses, move to Miami and leave thousands of workers unemployed – but that in reality they would never do so due to having so many family and other personal ties in the country. As Manuel Ayau Cordón told me, the power of the business sector comes from the fact that they ‘scare the hell out of the President because he doesn’t know enough’.

2. It’s easy to be mistaken about what motivates the oligarchs

The oligarchs are not simply motivated by money and power, as I had at first naively assumed. Many are motivated by fear. Several business leaders I interviewed had children or other family members who had been kidnapped for ransom and sometimes killed during the civil war by the URNG guerrillas, who targeted the elite, of course, due to their money and power. Many of those who supported the military’s extermination campaigns and paramilitary death squads did so not just to protect their assets but because of fear for their personal security or to exact revenge. Although the oligarchs did not suffer during the war on anything like the scale of Guatemala’s Indigenous population, understanding such personal experiences can be vital for explaining their support for the army.

3. Oligarchs love to talk if you make them feel comfortable

Getting the oligarchs to speak openly was a challenge. Using all I knew about ethnographic and oral history interviewing techniques, I tried to be courteous rather than confrontational – a strategy that created an atmosphere which felt relaxed, unthreatening and conversational. I quickly learned that accusing them of violating human rights or exploiting workers made them clam up. But encouraging them to tell stories about their own lives and experiences resulted in them letting down their guard and revealing much more about themselves. Rather than being critical of them on the spot during the interviews, I found that I could hold back my critiques for when I was later writing about them and interpreting what they said – which is what I do in What The Rich Don’t Tell The Poor.

Stepping back, my big picture learning is that we understand far too little about the oligarchs and this stands in the way of successful strategies of change. So remember this simple maxim: if you want to challenge the elite’s power, then first understand what makes them tick.

To find out more about What The Rich Don’t Tell The Poor and to get yourself a copy, visit Roman Krznaric’s website.

This first appeared on From Poverty to Power.

Photo by Vincent M.A. Janssen from Pexels