After Trump, the Groundswell of Global Climate Action is ever more Central to the Climate Regime

The Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action marks growing integration between the intergovernmental climate regime and cities, businesses, and other actors.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the UN climate conference that finished in Marrakech last week was how little the cataclysmic election of Donald Trump slowed the negotiations between the 196 parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Indeed, in many ways the shock accelerated countries’ work to build the new “pledge and review and ratchet” system they created at last year’s breakthrough summit in Paris.

It also brought even greater attention to climate action from cities, businesses, states and provinces, and other sub/non-state actors. Building on a major trend in the negotiations over the last two years, policymakers brought this “groundswell” even deeper into the intergovernmental regime at Marrakech.

The Paris Agreement created a broader and more flexible climate regime, in which countries make national pledges, which are then subject to international review, and which must be increased every five years. The brilliance of this new model—especially relevant after the US election—is that countries’ actions are no longer strictly conditional on other countries’ actions, a dynamic that bogged the climate regime into gridlock for two decades.

In Marrakech, big emitters like China and Saudi Arabia made clear that they will deliver their pledges even if Trump rolls back US climate policies. And in an extraordinary show of global unity—not a phrase commonly used in 2016—all 196 countries that make up the 22nd Conference of Parties (COP22) called for a redoubling of efforts in the Marrakech Action Proclamation.

What undergirds this commitment and momentum in the absence of binding international rules, and with fears for radical shifts in the policies of the world’s second largest emitter?

A big part of the answer is that bottom up action, which was featured as a central part of COP22 under the Global Climate Action (GCA) sequence, is increasingly reaching a critical mass. As analysis from Yale shows, the UN’s NAZCA platform, which tracks sub/non-state action, now includes:

• 2,508 cities from 118 countries, which represent 10.2 percent of the global population

• 211 regions from 31 countries representing 12.3 percent of the global population.

• 2,138 companies from 145 countries representing $36.6 trillion USD in revenue, roughly equivalent to the GDPs of United States, China, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

• 16 of the 20 largest banks representing $1.7 trillion USD by market capitalization.

These actions also add up in terms of emissions. While more data collection and analysis are needed, some studies show that the commitments made by sub-national governments and private companies, if delivered, could remove as much carbon from the atmosphere by 2030 as the 190 pledges nation states made in Paris. That could potentially close as much as two thirds of the remaining “emissions gap” we face to get the world onto a trajectory to limit global warming to two degrees or lower this century.

Even more remarkable, however, is how the groundswell of climate actions has moved from the periphery of the international regime to its core in just two years.

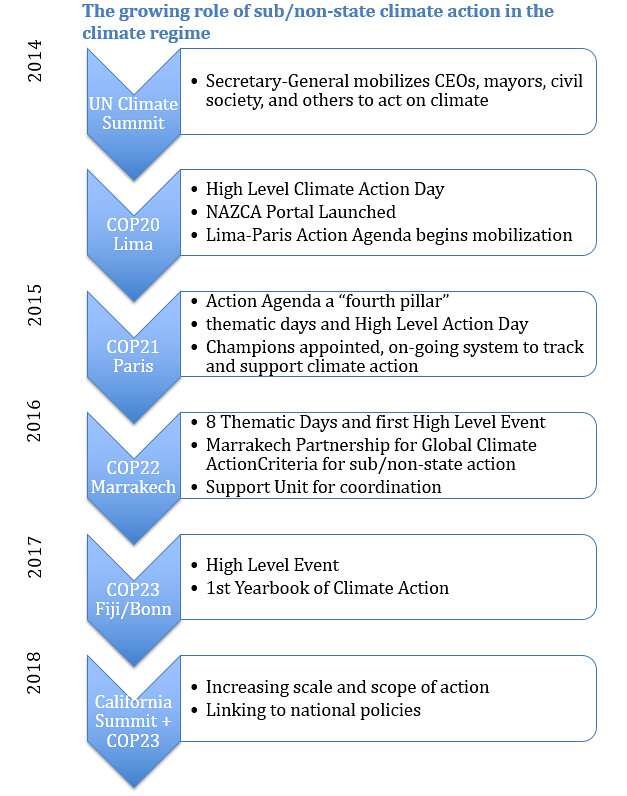

This process began with UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon’s September 2014 Climate Summit, which brought heads of state together with CEOs, mayors, and other leaders to announce bold actions on climate.

This dynamic was repeated two months later at a High Level Action Day at COP20, held in Lima, Peru. It was at this time that the UNFCCC, under the auspices of the Peruvian hosts, created its online NAZCA portal to track climate action by cities, businesses, and other sub/non-state actors.

Over the next year, the governments of Peru and France (the host of COP21), in partnership with the UNFCCC Secretariat and the UN Secretary General, worked to mobilize additional action and initiatives from all sectors of society. This “Lima-Paris Action Agenda,” as the programme was called, eventually came to include more than 10,000 individual commitments. It was declared a “fourth pillar” of the Paris climate conference, and cited as a critical driver of the successful outcome. Instead of being relegated to the side-lines, local and regional governments, the private sector, and other actors were showcased at a series of thematic days throughout the COP, and celebrated in a star-studded Action Day.

Countries got the message. In a major departure, governments in Paris created an on-going system to track, support, and accelerate sub/non-state climate action going forward. They appointed two High Level Champions to catalyse bottom up climate action. They recognized the NAZCA portal as the global system to track such actions. They mandated that a High Level Event be held at every COP for sub/non-state actors to announce new commitments and report on progress. And they decided to link the “Action Agenda” to the technical process in the negotiations through which countries consider new policy options they might adopt, so that sub/non-state action can inform national policy and vice-versa.

This new link between the intergovernmental sphere and the sub-national and transnational spheres sets, in many ways, a unique precedent in global governance. Just as countries are now working out how the Paris Agreement will function in practice, over the past year, the High Level Champions, the UNFCCC, and the community of sub/non-state actors that make up the groundswell of climate action have worked together to make the Action Agenda operational.

COP22 brought needed clarity to this process. The Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action outlines a light-touch coordination system for this new model. It specifies the role of the Champions to foster bottom up climate action in areas where it is needed, and to increase collaboration and linkage between bottom up action and countries’ policies. It enhances the tracking and transparency around the GCA by creating an annual Yearbook of Climate Action to assess the scale and scope of non-state action, and to feed it into countries as they implement and ratchet up their own policies. It sets criteria for sub/non-state actors’ participation in the GCA to enhance accountability and raise credibility. And it forms a Support Unit in the UNFCCC Secretariat to coordinate the process, bolstered by a hybrid support network envisioned to include a mix of governments, representatives of city and business networks, international organizations, and other actors.

As if often the case for new international initiatives, especially innovative ones, the practice has lagged behind the theory. The Champions only began their work halfway through 2016, and resource constraints and ongoing organizational questions limited their ability to maximize their potential (for example, many of the individuals supporting the Champions were working on a volunteer basis). Still, the results have been impressive, with several new initiatives launching during the eight thematic GCA days held during Marrkech, and a High Level Event that saw the launch of a new $1 million prize from the King of Morocco for bold climate action.

Looking ahead, we can expect the GCA process to continue to evolve in 2017 and 2018. As the tracking and mobilization functions become increasingly operational, it will be critical for the GCA to deepen the linkage between sub/non-state actors and national policies. Especially as countries begin to develop their next round of pledges for 2020, the groundswell of climate action will be aiming to:

- Help countries implement existing targets

- Show that higher ambition is possible, and build domestic constituencies for greater climate action

- Provide concrete ideas and policies that countries can use to scale up action

2018 is lining up to be the next milestone in this process. California is looking to hold a global summit that year for cities, businesses, states and provinces, and other sub/non-state actors, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change will publish a major new scientific report on the 1.5C temperature target, and countries have agreed to reflect on their collective ambition at COP24.

To succeed, GCA will have to accelerate so much over the next two years that 2018 becomes the tipping point at which the transition to a low carbon world becomes truly unstoppable. No one knows if this will work. But the way the new system has show resilience in the face of a major electoral surprise in a major countries bodes well. For an issue so long trapped in gridlock, the evolution of the regime at least creates the hope of possibility.

Thomas Hale is Associate Professor of Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. His research explores how we can manage transnational problems effectively and fairly. He seeks to explain how political institutions evolve--or not--to face the challenges raised by globalization and interdependence, with a particular emphasis on environmental and economic issues. He holds a PhD in Politics from Princeton University, a masters degree in Global Politics from the London School of Economics, and an AB in public policy from Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School. A US national, Hale has studied and worked in Argentina, China, and Europe. His books include Between Interests and Law: The Politics of Transnational Commercial Disputes (Cambridge 2015), Transnational Climate Change Governance (Cambridge 2014), and Gridlock: Why Global Cooperation Is Failing when We Need It Most (Polity 2013).

Photo credit: Zé.Valdi via Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA