Is Behavioural Economics (aka Nudge Theory) Blocking the Path to Progress?

Duncan Green explores a recent paper challenging the championing of nudge theory.

There’s been an upsurge in recent decades in tackling problems by trying to change the behaviour of individuals – behavioural economics, nudge theory and a proliferation of government ‘nudge units’. Now two disillusioned proponents, Nick Chater and George Loewenstein, have written an important critique of the whole thing, contrasting what they call the ‘i (individual) frame’ with the ‘s (system) frame’ as ways of thinking and making change happen. Some extracts:

First their ‘long abstract’:

An influential line of thinking in behavioral science, to which the two authors have long subscribed, is that many of society’s most pressing problems can be addressed cheaply and effectively at the level of the individual, without modifying the system in which individuals operate. Along with, we suspect, many colleagues in both academic and policy communities, we now believe this was a mistake.

Results from such interventions have been disappointingly modest. But more importantly, they have guided many (though by no means all) behavioral scientists to frame policy problems in individual, not systemic, terms: to adopt what we call the “i-frame,” rather than the “s-frame.”

The difference may be more consequential than those who have operated within the i-frame have understood, in deflecting attention and support away from s-frame policies. Indeed, highlighting the i-frame is a long-established objective of corporate opponents of concerted systemic action such as regulation and taxation.

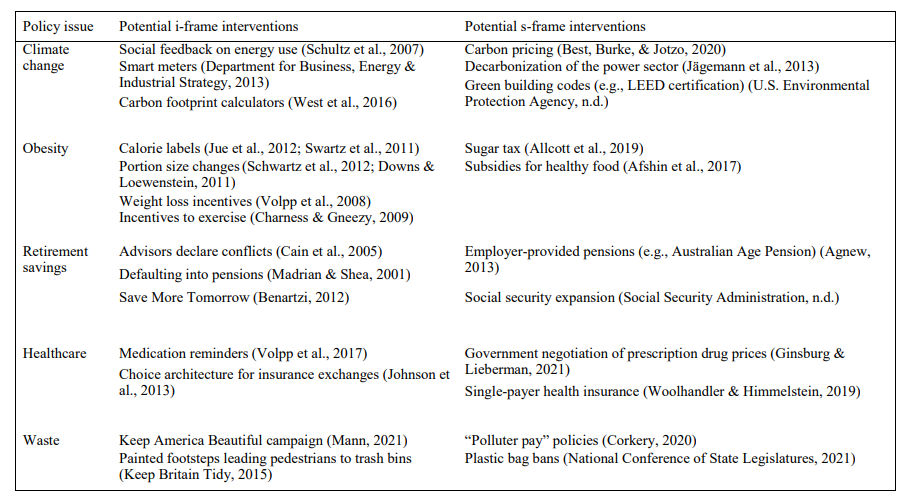

We illustrate our argument, in depth, with the examples of climate change, obesity, savings for retirement, and pollution from plastic waste, and more briefly for six other policy problems. We argue that behavioral and social scientists who focus on i-level change should consider the secondary effects that their research can have on s-level changes. In addition, more social and behavioral scientists should use their skills and insights to develop and implement value-creating system-level change.

Now some background:

The behavioral and brain sciences are primarily focused on what we will call the i-frame: that is, on individuals, and the neural and cognitive machinery that underpins their thoughts and behaviors.

Public policy, by contrast, is typically focused on the s-frame: the system of rules, norms and institutions by which we live, typically seen as the natural domain of economists, sociologists, legal scholars and political scientists.

Historically, i-frame insights have engaged with public policy primarily by providing evidence about which s-frame policies are required, or whether they will work. For example, research on basic neural and cognitive mechanisms of imitation has been linked to the likely impacts of TV or videogame violence, the power of advertising and so on. Work on the neuroscience and psychology of addiction has informed questions about whether, and how best, to regulate recreational drugs, cigarettes, alcohol and gambling. And, health psychologists and public health doctors have long focused on the physiological and psychological mechanisms that convert s-frame factors (e.g., lack of personal autonomy in the workplace, social isolation, and poor food environments) into poor outcomes for physical and mental health.

This important work uses insights about individual psychology to inform s-frame changes, to regulation, taxation, social support, or institutional reform. In the last two decades, however, there has been an increasing enthusiasm among both academics and governments for a more direct approach: using i-frame insights to create i-frame policies. The starting point is the thought that many of societies woes stem from individual-level human failings, including excessive self-interest, present bias, diffusion of responsibility, information avoidance and confirmation bias.

Unlike traditional policies, i-frame interventions don’t fundamentally change the rules of the game, but make often subtle adjustments that promise to help cognitively frail individuals play the game better.

A shift towards individual interventions is extremely tempting. Traditional public policy measures often get snared in legislative thickets (especially in times of political polarization) and entail costs perceived as daunting (especially in times of financial austerity). By contrast, i-frame policies typically focus on modifying policy implementation in ways that are cheap, quick and politically uncontroversial. The hope is that small changes can make a big difference. ’

And on a more personal note:

We have begun to worry that seeing individual cognitive limitations as the source of problems may be analogous to seeing human physiological limitations as the key to the problems of malnutrition or lack of shelter. Humans are physiologically vulnerable to cold, malnutrition, disease, predation and violent conflict, and an i-frame perspective on these problems would focus on hints and tips to help individuals survive in a hostile world.

But human progress has arisen through s-frame changes—the invention and sharing of technologies, economic institutions, legal and political systems, and much more, which created an intricate social, political and economic system that has led to spectacular improvements in the material dimensions of life. The physiology of individual humans has changed little over time and across societies; but the systems of rules we live by have changed immeasurably. Successful s-frame change has been transformative in overcoming our physiological frailties. We suspect that the same is true of our cognitive frailties.

And the final bit of public self-doubt:

Although today we see s-frame interventions as the path forward for behavioral public policy, we, and many other behavioral scientists, previously had a very different picture in mind: that, even where s-frame reform was required, a focus on additional i-frame interventions could only help. But if the right s-frame solutions were available but not implemented all along, it is likely that behavioral scientists’ enthusiasm for the i-frame has actively reduced attention to, and support for, systemic reform, as corporations interested in blocking change intend. We have been unwitting accomplices to forces opposed to helping create a better society.

Really interesting, and the case studies (see table for a flavour) are excellent. The full 28 page paper is well worth a read. I guess I like it because a) it’s yet another takedown of the magic bullet school of development that says ‘hey, we don’t need to wrestle with context, politics and power – we can fix everything with tech/microfinance/nudges/cash transfers/social enterprise etc etc and b) ex-proponents are often more convincing than diehard opponents.

Thoughts?

And here’s a rather more pro- approach I came across on YouTube, from Utrecht University:

This first appeared on From Poverty to Power.

Photo by Merlin Lightpainting