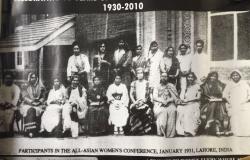

Being a Feminist Academic in Pakistan, and Why Open Access is Necessary for Decolonizing Academia. An Interview with Ayesha Khan.

I sat down recently with Ayesha Khan, who works with the Collective for Social Science Research in Karachi, Pakistan. She is author of The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy (2018). Her FP2P post on that book is here.

AK: Most of my professional life I’ve heard from detractors, both in Pakistan and internationally, who say ‘oh, you know, it was a small elite feminist movement – what did it ever really accomplish?’ And on the face of it, sometimes it’s hard to say! Because the status of women in Pakistan remains so compromised.

That motivated the book, but also my work since the book: because of the women’s movement activists’ engagement in politics, there have been a lot of gender equality policy outcomes – I wanted to trace how that happened. Then activists in other countries can say ‘hmm, under governments that are not too democratic or inclusive, how can women’s rights activists still make a difference?’

Under the dictatorship of General Zia-Ul-Haq in the 1970s and 80s, he brought in a lot of policies under the name of Islamicization that were discriminatory towards women and religious minorities, such as the blasphemy laws or the Zina laws that ban sex outside marriage. It’s been really hard, but the women’s movement has since been able to push back against some of the worst aspects of these laws. Since 2002, we have had reforms of the Zina laws and most importantly, on laws about electoral space – we now have an expanded gender quota for women in all legislative assemblies.

That really made it possible for women to air their voices in policy-making, they managed to push through sexual harassment laws, laws against customary practices such as the exchange of girls to settle tribal disputes, laws against acid crimes and honour killings and so on – if you open the spaces for women’s voices, things are possible! But it’s not possible without strong feminist leadership.

DG: What’s the dynamic between what’s happening in people’s lives, and what’s happening in Parliament?

AK: That’s a good question because many people say that a lot of these laws are still to be implemented – honour killings are still happening, even though the courts are now taking a stronger stand against them; domestic violence is still a problem.

So what’s the point? Sometimes we ask ourselves the same question! But the story from the women’s movement is that we saw in the 1980s when new discriminatory laws came into force under the Zia regime, they changed society. Social norms became more extreme against the rights of women. So we saw the impact of laws, and that is one reason why the women’s movement has been so focussed on changing laws.

And yes, laws do change norms. There are no women in jail for adultery today – before there were thousands. The rate of acid attacks against women has really dropped.

DG: Can we move onto what it’s like being a secular feminist academic in Pakistan?

AK: The problem is that over the last 30 years, talking about secularism or human rights has become branded as anti Islamic, bordering on blasphemous. The definitions of the words have become confused and clouded.

One result is that many feminist academics, especially the older generation who started their careers in the 1980s wanting to become academics, responded to the increasing restrictions by moving out of academia and opening their own NGOs and thinktanks, though which they conducted their own research.

In the last 10-20 years private universities have become stronger, and there are many more opportunities for young academics. But even there, students complain about my lectures on secularism and feminism, and you wonder how safe these spaces really are. Other professors have been denounced for secularism and therefore liable to charges of blasphemy – there are always extremist students on every campus. There are professors in Sindh and Punjab who are in jail under the blasphemy laws.

But I also find that students are hungry to hear another narrative. You cannot tell how somebody is thinking from the way they’re dressed – I’ve had students in my class in full burka, with their faces covered, who are progressive feminists at heart and want to know more. I try to give them the feminist language to critique what we saw happening in Pakistan, and that may also help them question their own lives.

DG: Let’s talk about your great book, published in 2018, but still not published in Pakistan. Can you explain?

AK: I tried really hard with my UK publisher for me to retain the rights to publish in English in Pakistan. But they refused. Foreign books are very expensive in Pakistan, and usually imported through India, but that route has also shut down. So the British edition of my book from IB Taurus, the publisher, cost 12,000 Rupees – £75. I have used author’s discount to buy books and then sell them at half that price, but even then, bookshops have said no. And so many publishers in Pakistan were willing to take it on.

Now what I’ve done is pay out of my own pocket for the book to be published in Urdu and it will come out later this year.

Open Access would be the perfect model – that was not available to me. In a country like Pakistan, where discourse is constrained, and access to libraries is limited, the future is digital platforms for both books and journals. I’m doing my PhD at the University of Sussex and the best thing about it is the library access!

DG: You mentioned your PhD by publication – could you explain?

AK: I’m doing it with the Institute of Development Studies. I was able to broach that idea because I’ve been a research partner of theirs in the Action for Empowerment and Accountability research programme. I wanted to use my book and my A4EA work for a PhD. When I searched, I found that UK Universities generally only offer this to existing staff, not people in other countries. But IDS was very supportive. I started in January 2021, but now 2 or 3 others have joined through the same route.

This is an excellent pathway for people all over the world who are partnering with development studies departments, allowing them to take their research to the next level.

DG: I find it bizarre that this kind of avenue of in depth enquiry is largely restricted to people in their mid to late 20s with access to funding, when there are so many people in mid or late career who desperately want and would benefit hugely from the chance to stand back and reflect on what they’ve done – rather than reflect before they do it, as is currently the case!

AK: Maybe we should do a PhD twice – when you’re younger it gives you the theoretical framing and conceptual clarity that you need going forward, then later on in life it allows you to reflect on all the empirical work you have accumulated over the decades.

This is also an important route to the decolonization of knowledge production. People like us, who have been living and working in Pakistan for decades, get our funding through the development networks – UK Universities who get the funds and then partner with us to do the empirical work. But we struggle to stay afloat in this way. We’re not the academic powerhouses – we are the source of grassroots findings, community-based knowledge, the local value chain. To get to the next level, we need the conceptual clarity and the academic rigour that sometimes we don’t have the time to develop.

In recent years, social sciences in universities in Pakistan have strengthened a little bit, but very few offer PhDs with global standing. So this is a great way for those of us who have been working in development for a long time to take a pause, use work we have done, and then locate it within global debates.

But in the end, it is also about the where the money comes from. There is a structural problem with funding for research, in that it doesn’t come directly to thinktanks like ours or even universities in Pakistan. But we can push back by chipping away, getting our PhDs while we’re on the job.

This post first appeared on Duncan's blog From Poverty to Power.

Image: Author's Own.