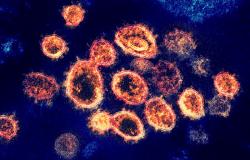

Developing countries urgently need more policy space to fight COVID-19

The global economic crisis triggered by the spread of COVID-19 has sent many of the world’s developing countries into an economic death spiral. At the first signs of panic in early March, investors fled to the ‘safety’ of deeper financial markets and the US dollar in particular. Capital flight, rising spreads, falling export revenues and collapsing exchange rates compounded an already precarious debt position in many countries, tipping a number into default and leaving many more in a high state of stress.

While the panic has subsided, thanks in part to a large dollop of dollars from the Federal Reserve, the IMF predicts the contraction in developing countries could, on average, be as much as 3% in 2020 – but with some countries and regions hit much harder. Another lost decade is on the cards.

Once again, the international regimes for trade and finance have revealed their inability to prepare for such shocks and to mobilise a rapid and commensurate response for vulnerable countries and communities. With an estimated $2 to $3 trillion payments shortfall facing developing countries over the next eighteen months, the liquidity support, debt relief and development finance they need to help navigate the crisis and begin to recover has been woefully inadequate.

Adding insult to injury, as the number of new cases and deaths continues to rise across the developing world and their fiscal space is squeezed by the onset of recession, recovery is being hampered by the protections granted to foreign investors in multilateral, regional and bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs).

The Intellectual Property side of these agreements has served the world poorly in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, including with respect to diagnostics, vaccines, and medicines. Although the COVID-19 genome – along with complementary scientific information – was shared early on, large proprietary corporations with a history of abusing such practices are now pursuing more siloed product development, inhibiting the prospective benefits of collaborative open science research and product development.

At the same time, as many of these corporations are receiving significant public support to keep them in business and, despite a poor record on vaccine development, they are cluttering the world with uncoordinated clinical trials in their race for super-profits resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. This will likely hinder the development and deployment of superior products from smaller entities.

The dangers of concentrating production within health-related global value chains has also been laid bare during this crisis. These chains are dominated by a handful of companies in China, India, the United States, and Europe with sufficient control over both supply and price to put short-term gains above the health of countries. In response, countries at all levels of development are looking to provide subsidies, tax breaks, and preferential treatment to domestic firms, especially their small and medium enterprises. Even though any such efforts to expand and diversify production would make global markets more competitive and keep prices in check, they could be challenged under trade and investment treaties. Already investment lawyers are readying their corporate clients for related rent-seeking opportunities emerging from COVID-19.

Exceptions for national security and public health emergencies are allowed under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and in regional and bilateral trade and investment treaties and could be called on to help countries protect this policy space for a rapid deployment of manufacturing capabilities, compulsory licences, and importing of generic medicines. However, there is a general lack of precedent in international trade and investment tribunals and the burden of proof is on the defendant, putting further pressure on countries as they are trying to combat the emergency. Furthermore, many developing countries lack the legal capacities to defend their emergency measures, if challenged in these fora.

After four decades under hyperglobalisation, a weakened multilateral system is no doubt in need of major reforms. However, developing countries should not be made to pay for its current failings in the middle of the biggest economic crisis since the 1930s. Instead, the international community should commit to the following measures to give them the fiscal and policy space they need to combat the crisis and promote economic recovery:

1. Increased fiscal space through an issue of up to $1 trillion of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights and immediate debt relief for all developing countries that face balance of payments and liquidity constraints.

2. A “Peace Clause” on COVID-19 related WTO and FTA cases enabling countries to quickly adopt and use emergency measures to overcome intellectual property, data, and informational barriers to COVID-19 related health technologies, with a permanent standstill in all relevant fora on claims on government measures implemented in the context of COVID-19.

3. The suspension of WTO and FTA negotiations, and no new commitments should be demanded until the crisis passes, in order to allow developing countries to reassess the flexibilities they need for their economic recovery and future resilience.

4. An immediate moratorium on investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) cases by foreign corporations against governments using international investment treaties, and a permanent restriction on all COVID-related claims.

These are urgent first steps, but there must also be a commitment to major reform of the architecture of global economic governance with the adoption of new multilateral principles for shared prosperity and a more resilient future. There is no better place to begin than with an overhaul of the rules of a multilateral trading system that have for far too long put the profits of the few before the health, wealth and happiness of the many.

Richard Kozul-Wright Richard Kozul-Wright is Director of the Globalisation and Development Strategies Division in UNCTAD. He has worked at the United Nations in both New York and Geneva. He holds a Ph.D in economics from the University of Cambridge UK and has published widely on economic issues.

Kevin P Gallagher is a professor of global development policy at Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, where he directs the Global Development Policy Center.

This article first appeared in Open Democracy on 13.7.20 and was re-posted under a Creative Commons Licence.

Photo by quapan on Foter.com / CC BY