COP15: “Kick Out Environmentalists and Industry”: Small Scale Fisheries, Conservation Economies, and Human Rights in the Convention of Biological Diversity

Emma Workman discusses the tension between environmental goals and economic goals, alongside the need for conservation economies in the context of the Convention of Biological Diversity.

Environmental goals regularly bump up against the realities of economic demand and governmental pushes for resource extraction. Take, for example, Northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire, a 5000 square kilometre area in the James Bay Lowlands. The Ring of Fire is both the second-largest intact peatland complex in the world, storing about 35 billion tonnes of carbon, and home to mass deposits of critical minerals, which both the Federal and Provincial government have expressed great interest in extracting. The original interest in the Ring of Fire was due to chromite deposits, used to make stainless steel. Now, the global market is interested in nickel, which is an important material for creating electric vehicle batteries. Thus, development in the Ring of Fire can, and has been, be framed as environmentally friendly.

The tension inherent in discussions about the Ring of Fire development is obvious—many believe that development is crucial for meeting our emissions targets, while others note the impossibility of reconciling the amount of carbon that would be released by development.

The Ring of Fire is one example of an issue that many environmental goals deal with: the need for economic development on individual, community, and country-wide levels, and the incommensurate nature of environmental goods and economic goods. While the Ring of Fire is a national discussion point, many smaller, local communities face the same issues, and feel misunderstood by environmentalists and industry alike. These smaller communities are often far more impacted by sweeping environmental regulation, despite generally creating a much smaller environmental impact.

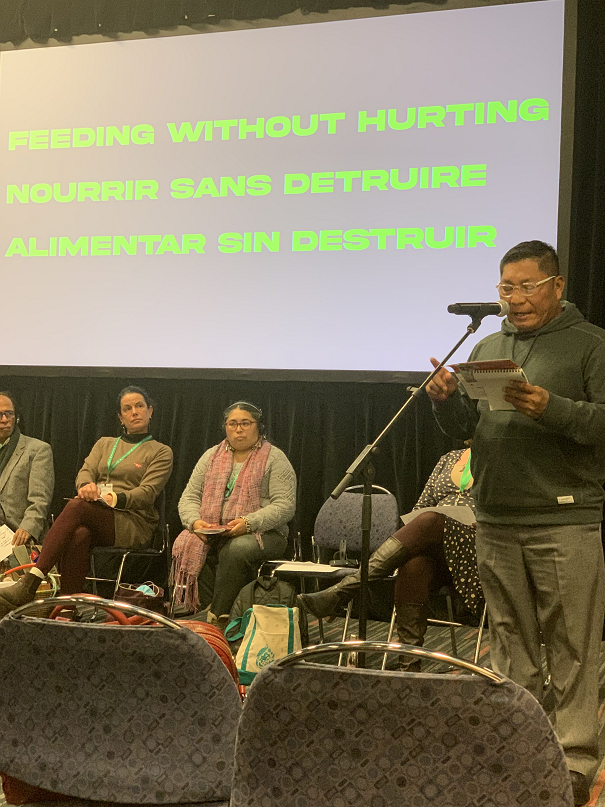

How can our environmental goals remain both realistic and ambitious, and consider the lived realities of many communities that rely on the environment to live, both materially and financially? Many groups at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) have stressed the importance of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) and their knowledge. Additionally, many IPLCs have discussed conservation economies and the necessity of supporting such economies in any biodiversity goals.

Small Scale Fisheries (SSF) and Conservation Economies

Small-scale fishers are one such group that advocated for a focus on human rights and IPLC involvement in environmental decision-making at COP15. Representatives discussed the value of SSFs to local communities, both monetarily and for their contribution to community values. Additionally, they levied criticism at some sweeping environmental goals, like 30x30 and the blue economy. These environmental goals, they say, are only useful if they take into consideration the needs of IPLCs. Citing the effect of lobbyists from the commercial fisheries, many representatives noted that SSFs were impacted by heavy regulation that did not impact commercial fisheries in the same way. This is despite the fact that many note the importance of small-scale fisheries in creating a sustainable seafood industry.

Small-scale fishers are one such group that advocated for a focus on human rights and IPLC involvement in environmental decision-making at COP15. Representatives discussed the value of SSFs to local communities, both monetarily and for their contribution to community values. Additionally, they levied criticism at some sweeping environmental goals, like 30x30 and the blue economy. These environmental goals, they say, are only useful if they take into consideration the needs of IPLCs. Citing the effect of lobbyists from the commercial fisheries, many representatives noted that SSFs were impacted by heavy regulation that did not impact commercial fisheries in the same way. This is despite the fact that many note the importance of small-scale fisheries in creating a sustainable seafood industry.

One solution proposed in the panel was co-management and decision-making abilities for IPLCs in biodiversity targets. Giving local communities a role in decision making is helpful for biodiversity, representatives noted, as they have observational knowledge and are the first to see changes on the ground. Additionally, SSFs advocated for prioritization of local communities in the fishery industry. This prioritization could be in the form of redistributive licences, in which SSFs have a higher percentage of fishing quotas; exceptions to fees; assertions of rights to access for SSFs near coastlines; or targeted local management rather than country-wide regulation.

These goals align with the concept of conservation economies, which recognize the crucial role of local communities in managing resources and stewardship of the ecosystems, alongside the need for employment. In the case of SSFs, this involves recognition of our biodiversity goals, alongside knowledge that 600 million people rely on fisheries for their livelihoods, and 3 billion people rely on seafood as a significant source of animal protein. That is, ambitious biodiversity goals need to take existing economic and social systems into account, even as they attempt to change them.

Conservation Economies and the Indigenous Village

Conservation economies were top of mind at the Indigenous Village, hosted by the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. Frank Brown, a member of the Heiltsuk Nation and adjunct professor in resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University, talked about the effects of “well-intentioned programs” on the ability for First Nations to prosper. These effects, Brown noted, come from environmentalists and industry alike. Brown described the shutdown of Indigenous fisheries because of the endangered status of herring, despite the First Nations practices that led to better conservation and biodiversity, such as preserving the strongest fish for procreation.

Often, IPLCs are forced to use governmental tools that don’t accord with their ideas about environmental protection—even designating national parks, with their stress on removing people and leaving land pristine, may not accord with the belief that human beings are one aspect of the environment. This can lead to less ambitious protection, in that privately owned land cannot be as easily protected. Linda Dwyer, a member of the Algonquin of Kitigàn Zìbì Anishinàbeg, discussed working with the Canada’s federal government to create a joint agreement under section 11 of the Species At Risk Act. The agreement never materialized, because once a critical habitat was defined under the Act, it required enforcement measures about people entering. For Dwyer, the critical habitat of the species intersected with many areas that Indigenous people lived—the two were not in opposition to one another. The sense that we are part of the environment and that conservation requires management and use creates a different, and perhaps more realistic, kind of conservation goal.

Emma Workman is a JD candidate at Osgoode Hall Law School.

Photo by Clive Kim

Conference images: Author's own