Women Ask Fewer Questions than Men in Academic Seminars

During academic seminars, any given question is 2.5 times more likely to be asked by a male than a female audience member. Alecia Carter reports on this research, which suggests that internalised gender stereotypes are at least partly responsible for the observed imbalance, both in men’s participation and women’s lack of it. The findings are important as having models one can identify with is key to how people perceive their possibility for success in any given career, and are particularly relevant in the context of the wider issue of the attrition of women in academia. While there is no easy fix, the data suggests that ensuring the first question is asked by a woman and having longer time for questions could ameliorate the imbalance.

It was just another departmental seminar. You know, the ubiquitous, weekly, invited-speaker-type seminar. But this one happened to be on gender differences in mental rotation tests. And this made something that I had noticed before at these events all the more salient: the majority of the questions asked after the seminar were by men. I mentioned this to my (male) colleague, who was quick to point out that the majority of the audience was women. He was right, but if you weren’t paying attention (as I hadn’t been), based on who spoke up at the end of the seminar you’d have thought the audience was mostly men.

Men ask more questions than women

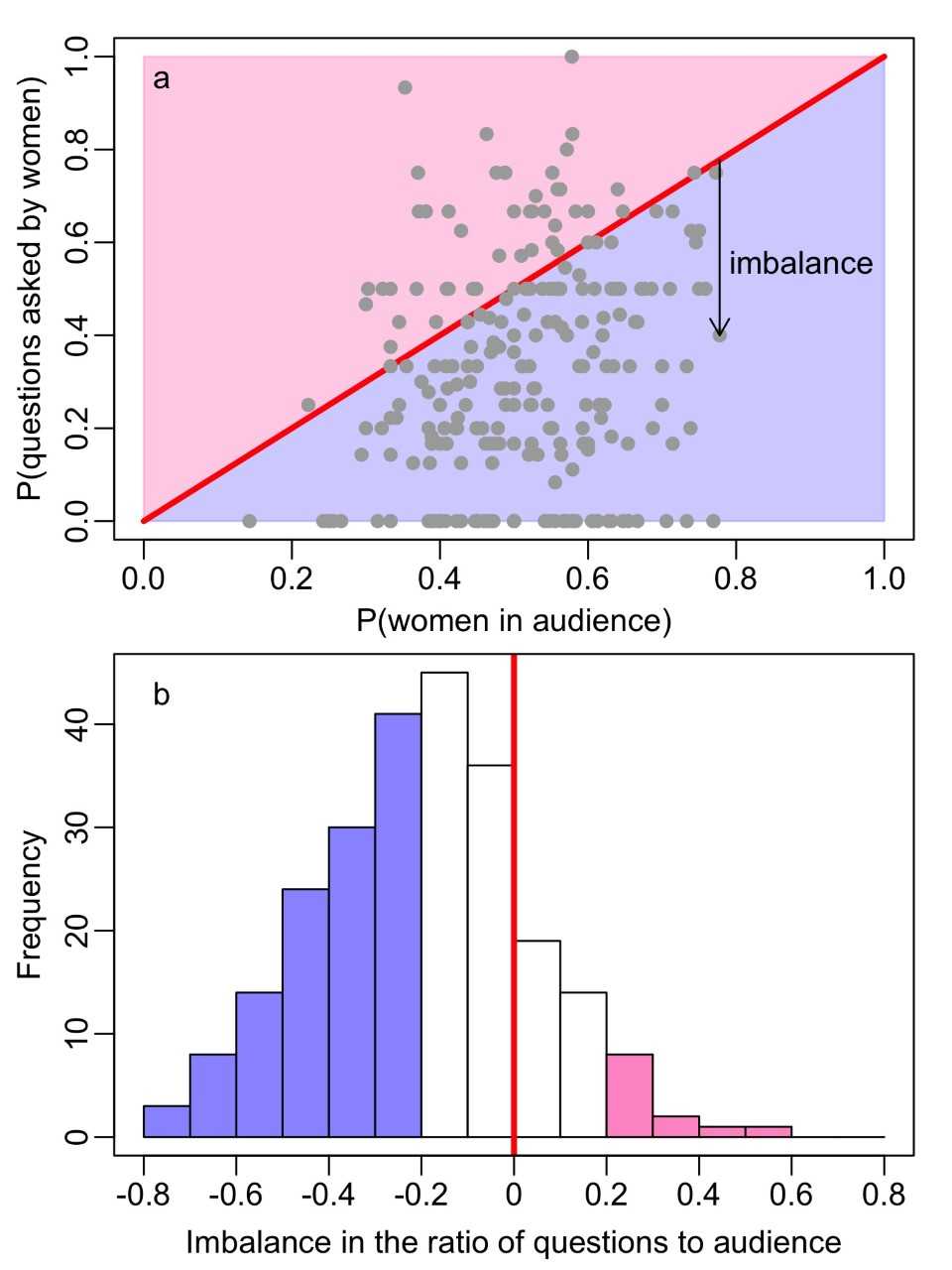

After three years of data collection across ten countries and nearly 250 seminars, we confirmed our original observation (Figure 1). Most audiences were, on average, not female-biased but made up of equal numbers of men and women, at least for the sample of biology, psychology, and philosophy seminars that we and our helpful colleagues attended. But any given question was 2.5 times more likely to be asked by a male than a female audience member. This was similar to what others have observed at conferences. Male audience members were disproportionately more visible than female audience members.

Figure 1: The gender imbalance in questions asked. Panel (a) shows a visual representation of what we refer to as an imbalance in questions asked in our data. The imbalance is simply the difference in the proportion of women in the audience and the proportion of questions asked by women. The arrow points to a seminar in which the proportion of women in the audience was 0.78 but the proportion of questions asked by women was 0.40. Thus, the imbalance was -0.38 for this particular seminar. Points falling in the lower blue half of the plot indicate an imbalance towards men, whilst points falling in the upper pink half indicate an imbalance towards women audience members. Panel (b) shows the frequency at which the imbalances were observed, with blue bins indicating seminars with questions disproportionately asked by male audience members and pink bins indicating seminars with questions disproportionately asked by female audience members. White bins indicate a moderate amount of imbalance (<|0.20|). In both panels, the red line indicates no imbalance (i.e. 0). Click to enlarge.

Now that we had verified that such an imbalance exists, we tried to understand it. Surely, we thought, this imbalance in question-asking behaviour could be explained by demographic inertia – it reflects that there are more senior men than women, and senior academics ask more questions than junior academics. But in an online survey we asked academics of all career stages how frequently they asked questions in seminars. Men self-reported asking questions more frequently than women irrespective of career stage; senior men ask more questions than senior women, just as earlier-career men ask more questions than earlier-career women. We also controlled for this in our analyses of the seminar data, but the proportion of female faculty at a particular institution did not predict the imbalance in the questions asked. Men just ask more questions than women.

What’s going on?

Where does this imbalance come from? There are two ways that women could end up asking fewer questions than men: either they put their hands up less frequently to ask questions, or they are overlooked when they do so. Both mechanisms could be in play, and I certainly witnessed some blatant occurrences of the second in my observations. But our survey data suggests that the first mechanism plays a major role – women report asking questions less frequently than men, remember – and they also provide some insight into why.

When asked what prevented people from asking a question when they had one, women rated internal factors, such as working up the nerve or being intimidated by the speaker, as more important than men, whereas there was no difference for external factors, such as having enough time. The survey suggested that internalised gender stereotypes are at least partly responsible for the observed imbalance, both in men’s participation and women’s lack of it.

Why does it matter?

Why should we be concerned about this gender imbalance in question-asking at seminars? If men want to ask more questions than women, it’s not necessarily a problem. However, much evidence suggests that having models that one can identify with is important to how people perceive their possibility for success in any given career. That there is an imbalance in men and women’s visibility thus poses a problem in the context of the wider issue of the attrition of women in academia — women acquire 59% of undergraduate degrees, but only 21% of senior faculty positions, an observation frequently referred to as the “leaky pipeline”.

For many students and early-career researchers, the departmental seminar is the first exposure to “real” research and researchers – it is an opportunity to witness, and participate in, the academic dialogue. The humble seminar is more than just a speaker’s opportunity to share their research and the audience’s opportunity to learn about it; seminars play a formative role in exposing potential future researchers to the environment and culture of their field. It can shape young academics’ impressions of who is successful in their field and what it takes to be successful.

Given the formative role of the weekly seminar and the context of wider problems regarding the attrition of women in academic careers, the gender imbalance in question-asking suggests a problem. The issue is not that anyone ought to feel pressured to ask questions at public events, but that the various psychological and sociological factors influencing question-asking behaviour feed into a larger problem of gender imbalance in the profession. Addressing women’s visibility at a local level early in the career pipeline could, hopefully, help to address the larger problem of gender imbalance in academia at later stages.

Can anything be done?

This is a tricky question to answer. Our goal is not to pressure women to be more assertive, or to suggest that men refrain from asking questions at these events. Certainly, the problem can only be addressed by lasting changes in the academic culture that break gender stereotypes and provide an environment that everyone can feel part of. We would all benefit from more voices being heard. However, until that time, small changes in behaviour might make a big difference.

Our data suggested two interacting factors that could ameliorate the imbalance: a longer time for questions and the first question being asked by a woman. However, these data are correlational and although it’s tempting to think that there could be an easy fix by manipulating these variables, we haven’t yet tested whether these factors do indeed change the imbalance.

Our best advice is for speakers, moderators and audience members to be aware of unconscious bias during question time. But more importantly, everyone could follow the golden rule: ask questions of others as you would have them ask questions of you. Don’t speak out of turn, don’t use question time to show off, and moderators: don’t overlook patient people with their hands up in the back row.

Alecia Carter is a research scientist with the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique at the Institite des Sciences de l’Évolution Montpellier, University of Montpellier. When not attending seminars alongside the study’s co-authors, Alyssa Croft, Dieter Lukas, and Gillian Sandstrom, she researches the behaviour of wild baboons in Namibia, trying to understand whether and how information is transmitted through their social networks. She is also interested in open science and the ethics of academic publishing.

This first appeared at the LSE's Impact blog.

This blog post is based on the author’s co-written article, “Women’s visibility in academic seminars: women ask fewer questions than men”, a preprint currently available at arXiv.

Featured image: Worship by Marcos Luiz, via Unsplash (licensed under a CC0 1.0 license).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.