Documentary Review: Love and Solidarity: James Lawson and Nonviolence in the Search for Workers’ Rights

Love and Solidarity: James Lawson and Nonviolence in the Search for Workers’ Rights [documentary film], directed by Michael Honey, 2016. 38 minutes, distributed by Bullfrog Films, DVD ISBN 1-941545-59-9.

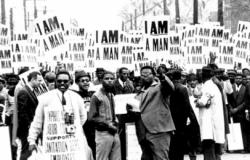

The documentary film 'Love and Solidarity: James Lawson and Nonviolence in the Search for Workers’ Rights' is an intriguing piece of work about the teachings and vision of Reverend James Lawson, and tries to show how his activist work has been an inspiration for movements from the early 1960s until today. In a short period of time, the documentary takes us from the U.S. southern civil rights movements and Lawson’s involvement in Martin Luther King’s following, to his work in the 1980s/90s L.A. workers movement, and finally The Dreamers, a recent movement of undocumented youth that has reinvigorated the debate on citizenship and migration in the U.S. The overall objective of the film seems to be, rather than providing a biographical picture of Lawson, to point out the historical similarities between these activisms, and more particularly, their shared roots in a philosophy of direct action and non-violence.

The film begins with a background on Lawson’s youth. We learn how after a racial slur was hurled at him in primary school, he got into a fight, and afterwards decided to never use his fists again. In the 1950s Lawson leaves for India, to study the teachings of Ghandi, and becomes more convinced of the non-violent cause and that it is the only way forward in the civil rights struggle in the United States. After his return, he offers his services to King’s civil rights movement. However, after the film is already halfway through, the viewer gets the feeling that he/she still does not know exactly what non-violence entails, how and why it is used and what the difference is with other (violent?) movements. This is not to say that the ingredients for the answers are not there. In fact, a strong point of the film is that it offers some rather unexpected perspectives and sources of inspiration. What is somewhat problematic however is that it is not always explicitly clear how these perspectives contrast and how they are related to the concept of (non-) violence. First of all, being a Reverend, religion and spirituality are obviously important sources of inspiration for James Lawson. Throughout the film he insists that his search has always been to find beauty and truth, which he asserts, are the building blocks of the Christian faith. So the Christian idea of ‘turning the other cheek’ forms a great inspiration for Lawson’s non-violence.

First of all, being a Reverend, religion and spirituality are obviously important sources of inspiration for James Lawson. Throughout the film he insists that his search has always been to find beauty and truth, which he asserts, are the building blocks of the Christian faith. So the Christian idea of ‘turning the other cheek’ forms a great inspiration for Lawson’s non-violence.

Given these Christian roots, a little more surprising is Lawson’s rather casual use of traditional leftist, Marxist analogies. At the beginning of the film he declares: ‘The human species was created primarily to learn to work (…) Work is not primarily for wages, but we are to be able to benefit from our work’. And later: ‘The economic order slams them, diminishes them, insists that they are but slaves, or property, or a commodity’. While the film does not elaborate at all on these remarks, it seems that for Lawson, to a certain extent the current capitalist system is an inherently violent system: to be successful as a capitalist, one has to be violent to the (body of the) worker, because exploitation of labor power is a basic building block of capitalist accumulation. But – akin to a Marxist narrative – the solution to all of this is also found in labor, because the process of labor is in itself not violent and destructive, but rather creative, transformative and liberating. In labor, Lawson says, the human being finds its dignity: so labor has to free itself from the – in the words of Slavoj Zizek – ‘objective’ violent and disciplinary systemic tendencies that it is confronted with.

However, while the film has thus a strong dose of ‘old-left’ labor union perspectives to it, it isn’t hard to bridge the gap with more contemporary, new left types of social movements. Lawson asserts that we need a worldwide, ‘massive non-violent movement’, to give democracy back to community and take it out of the hands of ‘addicted people of violence and wealth’. The comparison with the Occupy Movement and other ‘square’ movements of 2010-2012 comes to mind easily. Especially interesting here is Lawson’s notion that the non-violent approach insists that ‘ends and means are the same thing’. In other words, if one wishes to create a more socially just and less violent order, it is not enough to simply demand that change from politicians: you need to be non-violent in the way you mobilize, organize and work as a movement, in the here and now. This ‘prefiguring’ (living out the change one would like to see, bringing about a utopian future actively in the here and now) is very similar to Occupy’s ideology of ‘doing democracy’ . Non-violence as a strategy is thus an ‘exemplary practice’ of what society could look like, rather than simply engaging with/attacking the system and thereby inherently reproducing some of its violent hierarchies and disciplinary techniques.

As such, Lawson’s non-violence seems to be informed by an interesting mix of religious, ‘anti-capitalist’ and ‘prefigurative’ convictions. While the film certainly has these deeper analytical layers present, and provokes some critical thinking, it leaves quite some room for the viewer to find them: perhaps too much. Because the film is relatively short (38 minutes) and tries to address many topics, the viewer may get a little overwhelmed and is left more or less on his/her own to connect the dots. While it is clear that ‘non-violence’ has played a role in all the civil rights movements that Lawson has been involved in from the 1960s until the present day, which is the binding historical theme running through the documentary, the film perhaps lacks enough of an overriding framework for how to approach, analyze and understand this main concept in order to better grasp the connection between these struggles.

Despite this, the documentary seems to provide an authentic portrait of this energetic, positive, provocative and deeply committed man. Its overall strength is that it focuses on the possibilities of what can happen when people let their imaginations run free, instead of starting out with preconceived notions of who is ‘with me’ or ‘against me’: a non-violent movement thinks in terms of community and togetherness, rather than in terms of enemies and divisions. The film achieves a similar effect with its audience; as a result of its open character, one starts to wonder how such non-violent tactics apply to other social issues around the globe, and what other things might be possible through such a philosophy. In that sense, the film succeeds in the things that Lawson feels are most important: constantly being critically challenged and transformed as a human being.

Sander Mensink is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences at the University of Amsterdam.