Devising a 10-point plan on how to make the EU a stronger global actor: A European research adventure

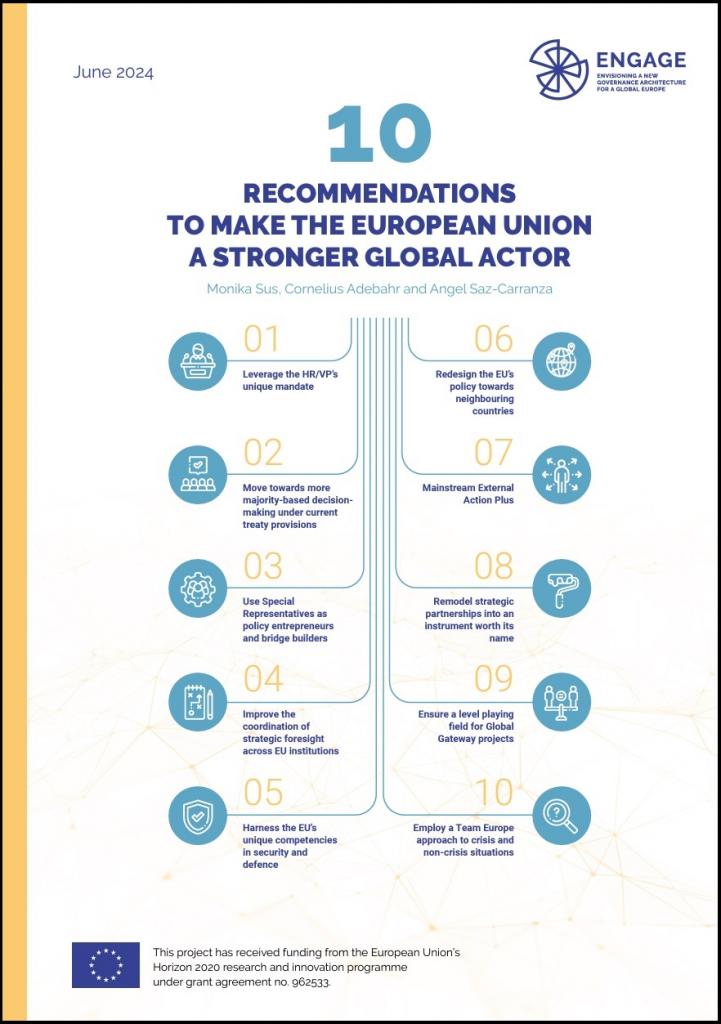

Cornelius Adebahr and Monika Sus details ENGAGE´s 10-point plan - presented to EU policymakers just days after the European election - to make the EU a stronger global actor.

The outgoing European Commission claimed to be geopolitical long before it had to be. And, truth be told, Europe is still far from being the global actor that it aims to be.

Yet, there is hope – and a plan. At least, that’s what a European research consortium ‘ENGAGE: Envisioning a New Governance Architecture for a Global Europe’ came up with.

Research projects funded by the EU’s Horizon Europe program tend to be unwieldy. They usually bring together more than a dozen academic institutes from as many countries, with a research agenda that includes precise milestones but is not designed to be flexible. That’s because the Commission officials in charge of this budget line need to make sure that the public money is put to good use.

In the social sciences, however, reality intervenes on a regular basis – just like in politics where strategic surprises have become the new normal. When the consortium partners conceived ENGAGE, the pandemic was not yet on the horizon. The project’s declared goal was to outline concrete proposals to improve European foreign policy, or as it was operationalized: to help the Union become a coherent, sustainable, and effective global actor.

When the project took off in early 2021, Covid was in full swing. The EU had barely escaped breaking point, what with border closures and bans on the export of medical equipment from one member state to another. How could one, at this moment, inquire about the EU’s global actorness? Soon enough, at last, Brussels not only led the internal vaccination drive, but was also instrumental in helping set up a global initiative against the pandemic.

When the project took off in early 2021, Covid was in full swing. The EU had barely escaped breaking point, what with border closures and bans on the export of medical equipment from one member state to another. How could one, at this moment, inquire about the EU’s global actorness? Soon enough, at last, Brussels not only led the internal vaccination drive, but was also instrumental in helping set up a global initiative against the pandemic.

This could’ve been a moment for the EU to shine, had it not been for two things: A return to old habits and national reflexes as soon as things started to normalize again, and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The former meant that the momentum for a more geopolitical EU was squandered, while the latter upended many previously held conceptions about European security.

It was in this period that ENGAGE developed a dynamic which was not foreseen in the original work plan. Many of the research questions carefully formulated at the outset and diligently studied in the process suddenly acquired a life of their own, and an urgency that came with it:

Should the EU still use strategic partnerships as a foreign policy instrument, if a country considered to be such partner had just attacked a peaceful neighbor? How would enlargement, the EU’s most successful foreign policy without ever being conceived as such, have to change once Ukraine, Moldova, and of course the Western Balkans countries were banging at the door? And now that everyone speaks about building up European defense, not least with a view to a fateful US election coming up in November, what would happen with the Union’s comprehensive approach running the gamut of external action, from trade and development cooperation to climate policies and conflict resolution?

At this moment, the strength of a multinational consortium with each project partner’s own networks came to bear. Based on extensive research collaboratively conducted by the 13 universities and think tanks, a series of policy dialogues were held over a period of ten months. The group thus met with policymakers in Bratislava, Madrid, Paris, Helsinki, London, Ankara, Berlin, Warsaw and, virtually, Kyiv to validate the preliminary findings in the face of political realities.

Out of over 500 pages of ground-laying research papers and action-oriented policy briefs, project leaders condensed a summary of only one tenth of this length. From this still very comprehensive analysis, they distilled key recommendations, which they discussed with EU policymakers in a workshop in Brussels in April 2024. Based on this feedback, as well as nearly a dozen reviews from former high level national policymakers and EU officials as well as key figures from other international organizations such as NATO and the International Crisis Group, the team of authors came up with a concise 10-point plan.

Not all these recommendations are earth shattering, and many have been discussed in policy circles and academia for years, if not decades. And yes, they shy away from treaty change – not out of a lack of ambition, but for very practical reasons: the end of the project coincides with the beginning of the 2024-2029 legislative period, and ENGAGE aims to propose a list of practical steps, to be implemented right away.

Our proposals will not be easy to put into practice, given a political environment of increasing polarization and diminishing public funds. This does not make them less urgent, though: whether it is about providing the next High Representative with tangible resources and authority to devise EU foreign policy, not just represent the position of the member states, often based on the lowest common denominator; about redesigning both enlargement and neighborhood policies to better reflect the realities in the EU vicinity, both east and south; about making a better use of the Team Europe approach and investing into member states’ defense capabilities; or about devising issue-based strategic partnerships worthy of the name and not just with like-minded countries but with those from the Global South where – precisely because of global tectonic power shifts – the EU needs to strengthen its relations.

ENGAGE´s succinct, yet comprehensive 10-point plan was presented to EU policymakers just days after the European election. Whether it can live up to its original ambition to make the EU a stronger global actor, and whether it will even be considered for implementation, is for others to decide.

What is certain, at least, is that the over 50 academics and experts, from junior doctoral researchers to established scholars, lived a truly European intellectual adventure. For what it’s worth, their collaboration has served to underscore the inherent value of the European project itself: With funding from European taxpayers, they contributed to a research agenda that had been formulated by the EU executive and provided tangible policy input from a dynamic research scene.

If nothing else, at least their work has been coherent, sustainable, and effective – just what the EU’s foreign policy should be.

Cornelius Adebahr, Carnegie Europe. Monika Sus, Hertie School & Polish Academy of Sciences/

Photo by Angel Bena