How Should Countries Distribute the “Burden” of Accepting Refugees Fleeing the Syrian Conflict?

Nancy Birdsall, Scott Morris and Anna Diofasi unpick the politics and numbers behind responses to the Syrian refugee crises.

The Europeans are struggling with the question—and considering agreeing to effective fines on themselves if they fail to meet targets on formal acceptance of asylum seekers. We don’t agree that refugees, who are sometimes but not always asylum seekers in the countries where they reside, necessarily constitute a burden; the evidence is compelling that countries benefit from immigration, particularly if immigrants are already well-educated, working-age adults, as is the case with most of the Syrians fleeing war at home. Still, there are real economic, security, and political costs of hosting refugees when, as with the Syrians, the arrivals are sudden and substantial.

Given those costs, how should we think about the obligations of potential host countries? Should the question be framed as a moral obligation? Among recipient countries, should the obligation be greater for countries that are geographically closer, or more similar in religious, cultural or other dimensions? But what if they are poorer than other nearby countries where refugees seek respite? And is the obligation of a host country greater if it played some role in generating the conflict that created a refugee problem in the first place?

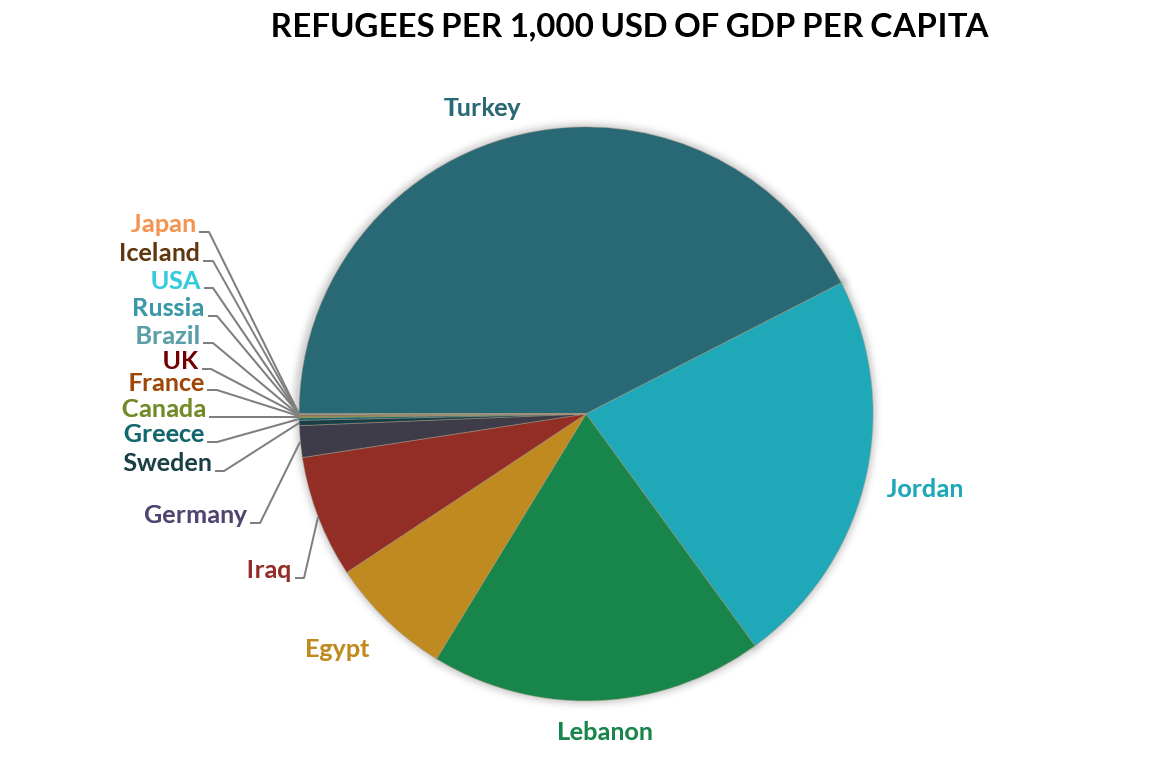

Developing countries are bearing the greatest “burden”

In the pie chart and table below, we make a start at thinking about these questions. And our calculations throw up some striking and disturbing truths. The pie chart makes clear that developing countries are bearing the greatest “burden.” It also shows the tiny “burden” the United States has so far accepted. As Americans, we are struck by that extremely limited role. It stands in striking contrast to earlier refugee episodes such as Vietnam and Cuba, when the United States accepted refugees in the hundreds of thousands.

The data we collated is presented in the table at the bottom of this blog, and provides more details of our findings. For each country where any Syrian refugees currently reside (whether they are seeking asylum there or not), we show the numbers of those refugees alongside the recipient country’s non-refugee population and its total economic size and current per capita income—and we provide a ratio of refugees to population size and to per capita GDP.

With the sole exception of Germany, with our rough estimate of 500,000 Syrian refugees (see sources and note for the table), the largest numbers of refugees are residing in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Egypt—countries that are near to Syria and share to some extent the language and religion of most Syrians. (Proximity to home makes an eventual return seem more likely, but many of those refugees have been outside Syria for more than two years.) This is not surprising. With the exception of Sweden, these countries also have the highest ratio of refugees to population size—also not surprising.

But what is striking is that the nearby countries with high numbers of refugees by every measure in the table are also the poorest (on the basis of per capita income) of those listed.

Millions left in limbo

To be fair, it is also true that the United States continues to “accept” the largest number of refugees globally. Here, definitions matter. The very large Syrian refugee populations in countries like Germany and Turkey are residing there without permanent status or any certainty about their futures. Syrian refugees currently residing in the United States, like all refugees accepted by the US, have permanent status and a path to citizenship. That’s good, but it's also part of what makes the Syrian refugee crisis a crisis.

Countries like the United States that are ultimately willing to accept refugees on a permanent basis are exceedingly slow in doing so. Of the 10,000 Syrian refugees the US government pledged to resettle by October this year, fewer than 1,800 have arrived in the country thus far. And as months turn into years, millions of Syrian refugees remain outside the United States in limbo, unable to adequately provide for their own families or contribute to their full productive potential where they are – and increasing spending on humanitarian aid that could better be spent helping them settle abroad.

As American citizens and taxpayers (Birdsall and Morris) in a country of immigrants, whose greatness has been forged by immigrants, we find the situation troubling. Surely countries like ours can do better, satisfying security concerns while responding to the clear humanitarian needs presented by this crisis… and ultimately, as we have seen in prior waves of refugees, benefiting from the productivity, talents, and patriotism of our newest citizens.

Table 1. Estimated number of Syrian refugees by select host countries and host country characteristics

|

Country |

Estimated number of Syrian refugees 1 |

Host country population (2011) |

GDP per capita (2011) |

Refugees per 100,000 of host population |

Refugees per 1,000 USD of GDP per capita |

|

Turkey |

2,750,000 |

73,199,372 |

10,584 |

3,757 |

259,826 |

|

Lebanon |

1,048,000 |

4,388,637 |

9,132 |

23,880 |

114,761 |

|

Jordan |

643,000 |

6,181,000 |

4,666 |

10,403 |

137,805 |

|

Germany |

500,000 |

81,797,673 |

45,936 |

611 |

10,885 |

|

Iraq |

246,000 |

31,810,191 |

5,839 |

773 |

42,131 |

|

Egypt |

120,000 |

83,787,634 |

2,817 |

143 |

42,599 |

|

Sweden |

107,000 |

9,449,213 |

59,594 |

1,132 |

1,795 |

|

Canada |

26,859 |

34,342,780 |

52,087 |

78 |

516 |

|

Greece |

22,000 |

11,104,899 |

25,915 |

198 |

849 |

|

France |

11,000 |

65,342,776 |

43,808 |

17 |

251 |

|

UK |

9,000 |

63,258,918 |

41,020 |

14 |

219 |

|

USA |

3,687 |

311,721,632 |

49,781 |

1 |

74 |

|

Brazil |

2,000 |

200,517,587 |

13,039 |

1 |

153 |

|

Russia |

1,600 |

142,960,868 |

13,324 |

1 |

120 |

|

Japan |

50 |

127,817,277 |

46,204 |

0 |

1 |

|

Iceland |

50 |

319,014 |

45,971 |

16 |

1 |

Sources: UNHCR, World Bank, Government of Canada, US Dept. of State, Die Welt, Al Jazeera, Voice of America, The Telegraph, The Japan Times

This post first appeared on the Center for Global Development's blog.

Photo credit: FreedomHouse via Foter.com / CC BY

Notes

Estimated number of Syrian refugees from the ongoing civil war (from 2011 to today) physically residing in the country, regardless of asylum application status as of May 4, 2016. For Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt the figures reflect the number of registered Syrian refugees in the country (as per UNHCR). For Sweden, the UK, and France, the figures reflect the number of official Syrian asylum applicants (as per UNHCR), though these are likely to be underestimates. The figures for Germany and Greece are based on government officials’ statements to the media and are above the number of officially registered asylum applicants (279,000 for Germany and 5,600 for Greece). The figures for Russia and Japan come from media reports and reflect the number of estimated asylum applicants in the countries. The rates of approval for both of these countries are reported to be much lower than for the European countries listed. For the US, Canada, and Brazil the figures reflect the number of refugees whose applications have been approved and who have arrived to the country.