Building Digital Nations: The World at Your Fingertips

From communist rule to the world’s most digitally advanced country, Joseph Dunn explores the challenges facing Estonia in driving productivity.

As the infamous hammer and sickle flag was lowered in Moscow for the final time, below in the Red Square thousands watched on as communism came to an end in the western world. Following the Soviet Union’s crumbling demise in 1991, numerous Soviet states regained their independence. One such country was the north European nation of Estonia.

Finding themselves once again as a sovereign nation, Estonia used the opportunity to innovate interactions between the public and private sector to create an ecosystem which promotes productivity, the likes of which we have never seen before. But will we see it again?

It is a surprise to some that today Estonia is considered the world’s most digitally advanced country. Having invested heavily in information sharing technology and security over the past three decades, the nation has revolutionised the way in which domestic affairs are carried out. Embracing the movement of avoiding human contact at all costs, citizens and Government alike can interact through online services established to create an e-society. Known as E-Estonia, the society allows common tasks to be completed saving time, money and even lives in the process.

Currently, 99% of all public services are available through E-Estonia. From voting to online banking, it’s all a mere click away. E-Ambulance even allows paramedics instant access to citizen health records in emergencies. An innovative idea that, as always, seems obvious in hindsight. In fact, there are only 3 main things human interaction is currently judged to be necessary for. Marriage, divorce and buying real estate. But, I have it on good authority that they are working on it!

The coming together of government and citizens in such an innovative way vastly reduces coordination failures between sectors, saving millions of pounds and a reported 1400 years of working time for Estonians every year.

The discovery of all this extra time in the day has huge implications for boosting productivity. In Estonia, a company can be registered in 18 minutes, and in 2014 it became the first nation to offer e-residency to people from abroad; enabling entrepreneurs from Europe access to the same electronic services as domestic residents. It even offers entrepreneurs from the UK a glimmer of hope in a post-Brexit world. The high levels of efficiency and inclusivity have led to growing productivity over the past decade.

This achievement is no mean feat; many large economies can only look on with envy as they continue to address stagnant growth following the global financial crisis of 2009.

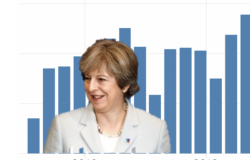

The graph seen below demonstrates Estonia’s productivity index since the crisis (with a few modifications). The question is, how viable is it for other nations to adopt this system. Is E-Estonia just a unique product of a small and relatively new society?

Whilst a country with long-established institutions may struggle to achieve the same success. Others have speculated that the software may in fact, birth new countries, not the other way around. Journalist Ben Hammersley envisages a world, where nations are born through social groupings based on preference of online interface and accessibility to digital infrastructure. Much like how people change banks based on the quality of their online banking apps, whole states can be programmed and joined digitally by those who prefer it to existing infrastructure. Perhaps even forcing government innovation through competition. After all, the public sector is known to prioritise everything at the same time, doing everything and nothing simultaneously.

There still remains a lot of speculation, but also opportunity. This week at the Global Entrepreneurship Congress in Bahrain former president of Estonia Toomas Ilves has been invited to talk his about his nation’s unique position. The conversation will undoubtedly inspire further exploration of the possibilities.

Joseph Dunn is a second year BSc Economics student at the University of Sheffield and policy analyst at the GEC 2019. This post is part of a series from the Global Leadership Initiative's team of eight students at the Global Entrepreneurship Congress 2019 in Bahrain from 15th to 18th April. To read there rest of the team's outputs, please see here.