Positive Male Engagement in the WPS Agenda will take More than ‘Good Men’

David Duriesmith identifies tensions created by efforts to ‘engage’ men and boys in Women, Peace and Security, and introduces his new working paper: ‘Engaging men and boys in the Women, Peace and Security agenda: Beyond the ‘good men’ industry’.

What role might men and boys play in promoting gender equality after large-scale violence? Violence committed by men has been a central target of the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda over the past seventeen years. But until recently, far less attention has been paid in WPS to potential positive contributions of men and boys in achieving the goal of gender-equitable peace. In an attempt to rectify this deficit, the United Nations Security Council and international NGO’s have called for renewed efforts to bring men into the WPS fold.

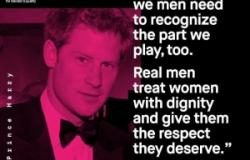

The most visible answer to the question of men’s role in WPS is a range of programmes and campaigns that have set out to ‘engage’ or ‘enlist’ men as potential agents of change. These endeavours, which my working paper calls ‘engagement work’, involved a range of attitudinal change programmes which work directly with groups of men or conduct awareness campaigns, for the purpose of encouraging men to become partners in bringing about the aims of the WPS agenda. While relatively recent to WPS, ‘engagement work’ has a far longer history in men’s pro-feminist activism, national anti-violence programmes, and highly visible gender-equality campaigns, such as the United Nations recent HeForShe campaign.

At their best, these programmes have tried to present pro-feminist politics to men in locally salient ways that ask them to reconsider their practices, attitudes and attachments. But at its worst, ‘engagement work’ calls for ‘real men’ or ‘good men’ to stand up for women by protecting them. Anti-rape efforts, like the long-running My Strength Is Not for Hurting campaign, draw on tropes of masculine strength in the hope that with enough work ‘real men’ can be turned from problems to protagonists in the fight for gender equality. With the United Nations calls to enlist and engage men and boys in WPS, these engagement techniques are now being drawn on with the intention of creating peaceful men.

As WPS now begins to turn to the subject of men, it’s time to consider the history of ‘engagement work’ outside of the agenda and reconsider the role it might have in achieving a gender equitable peace. It is with this intention that my working paper charts the emergence of professionalised ‘engagement work’ within pro-feminist men’s groups and suggests that current shifts to engaging men and boys in the WPS agenda risks replicating the failures of the past. Current engagement work has learnt from previous movements’ techniques, concepts and political orientations.

The techniques which are most prevalent in contemporary ‘engagement work’ were pioneered in pro-feminist consciousness-raising groups. Men who came to support the feminist movement found that despite adopting these politics, their attachments and desires were difficult to disentangle from male supremacy. To remedy this, men came together in group settings where they could challenge one another’s unconscious attitudes and enduring patriarchal practices through collective action. These consciousness-raising techniques did not begin as an attempt to convince men to support feminism but started as a form of feminist praxis from men who wanted to live pro-feminist lives.

In contrast, current examples of ‘engagement work’ tend to represent external attempts to change the attitudes of men, often on a limited range of attitudes. The disjunction between the origins of these techniques and the current shape of this work has resulted in a number of tensions. The working paper highlights six tensions between the goals and activities of pro-feminist projects that have resulted in the most problematic examples of ‘engagement work’ and suggests potential remedies for future attempts to address men and masculinities within the WPS agenda.

These tensions are seen in efforts which have a lack of clarity, projects that reify masculinity, agendas to engage men without holding them responsible, those who hold up dominant men as ambassadors for change, programmes which have co-opted feminist spaces, and the creation of a neoliberal ‘good men’ industry. The above tensions result in contradictory efforts to enlist men, which on one hand call for loosening the bonds of gender, and on the other tell men that they need to step up as real men. The imprecision and reification results in setting men a low bar for involvement in feminist politics while reinforcing oppressive practices as natural or inevitable. Particularly within conflict-affected regions of the Global South, these tensions risk making overtures to the intersections of race, class, sexuality and gender while drawing on neo-colonial logics of white expertise and barbarous masculinity in need of salvation.

In a context of limited funding and political will, it is essential that wealth and toil are not expended on attempts to engage men and boys in the WPS agenda which have not first considered these tensions and properly articulated their contribution to the broader agenda. To do this, responses need to undertake the difficult work of untangling the relationship between men, their attitudes, their affective attachments, their practices and social structures. Different understandings on this question result in different appropriate responses: for example an attempt to unmake masculinities, to play with or disrupt masculinities, or to recreate positive forms of masculinity.

These different understandings also require fundamentally different policy responses if they are to contribute to the WPS agenda coherently. If this kind of clear delineation isn’t done, ‘engagement work’ risks remaining tokenistic, or worse, preoccupying itself with demanding that some of the most marginalised men in conflict zones solve the patriarchy, while doing little to unmake the underlying structural and discursive factors that make masculine violence possible.

David Duriesmith is a Post-doctoral Fellow in the School of Political Science & International Studies at the University of Queensland, Australia.

This post first appeared on the LSE's Women, Peace and Security blog.

Image Credit: HeForShe social media ad campaign.