Is Putin Stronger than Inflation?

Macho, tough-talking, strongmen have shaped the 21st century’s politics. In fact, the century began with the archetype of contemporary strongman politics, Putin, being elected on December 31, 1999. Since then, this new genre of right-wing populists has displayed how mighty they are by bending rules and moulding their countries by force. But Can Cinar argues they are soon to face their hardest challenge.

Leaders like China’s Xi Jinping and Nicaragua’s Ortega scrapped term limits, while the Phillipines’ Duterte and Thailand’s Chan-ocha removed democratic constraints by using the armed forces like mob bosses. It is not just constitutional changes; strongmen are powerful enough to even reshape gender relations and definitions. TV networks owned by Berlusconi, who rather easily survived multiple sex scandals involving minors, inundated Italy with representations of submissive women. Elsewhere we have seen strongmen attempt to make their nations more manly by boasting about the size of their chest, penises and their height, while enacting laws targeting “gay propaganda” and calling women sluts and bitches.

But still, are they strong enough to increase the value of their currency?

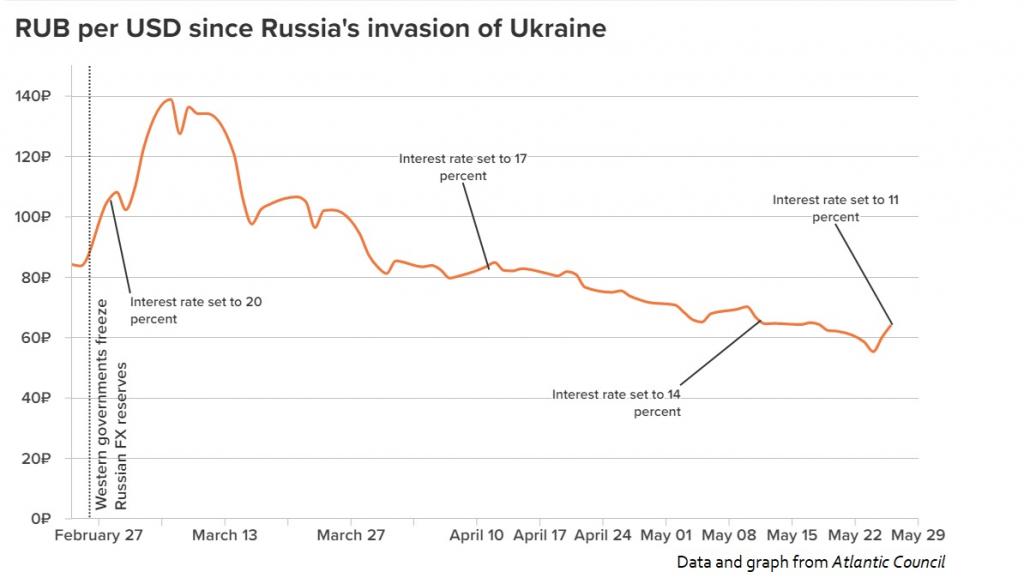

Amid an ill-fated war and unprecedented sanctions, the Russian Ruble managed to hit a 2-year high against the dollar in April and has been able to keep its ground for two months now. Much of the credit for this recovery was given to Putin, even in the Western media. However, a brief look at the history of ‘strongmen politics’ shows that it is not Putin’s economic genius or his ability to mobilize supporters that triggered the rebound. Exchange rates are much harder to bully.

The value of their national currency is extraordinarily important for these leaders. It is seen by many as a source of their reputation, aptly termed as ‘exchange rate populism’ in academia. Fluctuations in currency values are usually neutral events in economics, they are neither good nor bad.

For some countries, a currency losing value can lead to an increase in the balance of trade as it decreases the cost of production and improves the competitiveness of domestic goods internationally. Residents of a country with a depreciating currency would enjoy a relative increase in the value of their foreign currency asset holdings, while the nominal interest payments on government-issued sovereign debt shrinks. Letting the currency devalue opens up more space for monetary and fiscal intervention from the government too. It’s not only the government that benefits either, inflation chips away at household debt as it shrinks outstanding liabilities of debtors, and almost everybody is a debtor today.

And yet, leaders of countries that are running large trade deficits, struggling with massive household debt levels and with no space for monetary manoeuvres, like India, fight tooth and nail against any sign of inflationary pressure. In 2016, soon after boasting about his 56-inch chest, Modi decided to withdraw 500 and 1,000 rupee banknotes from the economy which extinguished 86% of the cash in circulation overnight. The reasoning given was to curb the black economy but considering that India suffers mostly from more structural and not petty corruption, it became clear that the experiment was to stop inflation. It worked well as consumer prices hit their lowest level in years, if we ignore the extreme hardship suffered by the poor. Nonetheless, inflation started picking up again by 2018.

It is not catastrophic Covid responses or a stagnating economy that poses a risk for the image of strongmen; it is the devaluation of their currency in the international market.

In 2018, when the economy faced large corporate defaults and drug shortages, Erdogan attempted to mobilize his large base by urging them to sell their dollars:

“If there are euros, take these out … immediately give these to the banks and convert to Turkish lira and, by doing this, we fight this war of independence and the future. Because this is the language they understand.”

In the same year, over 26 million people had voted for Erdogan, but his declaration of an independence war against dollar failed miserably as lira immediately lost value after the call.

A brief analysis of the struggle of strongmen against inflation over the last 22 years reveals statistically significant results indicating that the immediate effect of their calls to stop inflationary pressure is ineffective and actually causes an increase in inflation within two years. (1) Even utilising their popularity with a very large supporter base to fight against the international market’s devaluation of their home currency fails inevitably.

The only success strong leaders have in stopping devaluation is through blunt interventions into the functioning of central banks or extreme capital controls, like the ones Putin employed after the invasion. The message was that the strong Ruble proves that Fortress Russia can withstand any sanction.

The reality beyond the fictional number of the exchange rate is different though. Recent data shows that the Ruble in the international market is illiquid, which means demand for the currency is purely domestic. Doubling the interest rate from 9.5% to 20% has already started squeezing the banking sector and debtors in the country. A strong Ruble will punch a hole in the state budget as the main source of Russia’s revenue is denominated in foreign currency (energy taxes) while the government’s spending is in Rubles, which will amplify the deficit.

In times of war, capital is destroyed and demand for labour increases. The shortage of resources and increased demand from the government inevitably creates inflation. This is a natural response to radical changes in the supply and demand. Furthermore, recent studies show that post-war inflation leads to progressive taxation and generates strong redistributive mechanisms.

Fighting against inflationary pressure is like fighting against gravity. And even though Russia’s spurting and struggling war-machine has been relatively successful in that, it just means that the downfall will be that much harder.

Can Cinar is a political economist teaching at Durham University. His main research interests are in post-Keynesian economics and applications of Modern Monetary Theory.

Image: haberlernet NET via Flickr Public domain

Notes

- The dataset of ‘strongmen’ which I compiled consisted of: Trump, Erdogan, Modi, Bolsonaro, Orban, Salvini, Aliev, Xi Jinping, Salman, Johnson, Putin, Ortega, Maduro, Duterte, Chan-ocha, Mayardit, Ben Ali, Mugabe, Mnangagwa, Mubarak. I used lags of the quarterly annualised percent change in the CPI and speeches of leaders that mention curbing inflation, P-value < 0.05. For the dataset and analysis please contact me: can.cinar@durham.ac.uk.