Women’s Rights in “Weak” States: The Promises and Pitfalls of Gender Advocacy in Transition

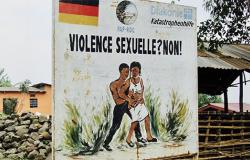

Milli Lake explores how and to what extent the spotlight on sexual violence has restructured judicial priorities in eastern DR Congo and South Africa.

Following a reported decline in conflict-related sexual violence in DR Congo, the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict recently referred to the country as its “most successful story” yet.

The Special Representative’s claim has been hotly disputed, not least because instances of gender violence are hard to measure. Yet few can deny the extent to which public resources and attention have been diverted towards resolving gender violence in the country’s east. For a number of years, gender violence constituted the core policy priority for donors, aid organisations and NGOs. Indeed, advocacy organisations and women’s rights groups were so successful in centering gender issues that they have sometimes given the impression rape is the only issue NGOs care about. The effects on local justice sector institutions have been so far-reaching that many believe the only way to get cases taken seriously by the country’s courts is to bring a charge of rape.

Meanwhile in South Africa, advocacy around the country’s so-called “rape crisis” has also garnered global attention. But despite comparably high reported rates of sexual and gender-based violence, extensive media coverage, and enduring pressure from civil society, activists have struggled to make sexual violence a lasting political or judicial priority. Nominal commitments from government have resulted in hollow policy concessions. And women’s rights are marginalised by many of the country’s institutions. Bringing sexual violence cases to court proves especially challenging as rape dockets are frequently lost or stalled by police and prosecutors.

When does targeted human rights attention reshape local priorities?

When does targeted human rights attention reshape local priorities?

Why has the spotlight on sexual violence restructured judicial priorities in eastern DR Congo while the issue remains marginal in many of South Africa’s institutions? And what do these divergent experiences tell us about trajectories of gender violence and reform?

In my new book I show that domestic and international human rights actors can exploit opportunities created by state weakness to directly shape the work of local institutions. Contrary to predictions that new human rights laws are most likely to take effect in countries with entrenched democratic institutions, I show that the diffusion and implementation of evolving human rights norms can rapidly take root in weak or transitional states.

A burgeoning body of scholarshipsheds light on the ways in which mass violence and political transition can create space for gender (and, by extension, other human rights) reforms. Rather than serving solely as a force for destruction, war and political transition can give rise to rapid and progressive periods of social change. By reconfiguring political power and disrupting existing social hierarchies, women and other marginalised constituents can enter new political spaces.

This is partly because non-state actors already assume responsibility for an array of governance activities. Well-organised local human rights coalitions, particularly those backed by local partners and international resources, can easily mobilise to exert influence in areas where governments lack reach, capacity, or interest.

War, political transition, and so-called state collapse also create legal and institutional opportunity structures. As new laws are passed, constitutions rewritten, and institutions born, human rights actors can capitalise on institutional change and disjuncture to lobby for the incorporation of language and principles that activists can later use to claim new rights.

Finally, stakeholders can use capacity-building projects in states designated as “weak” by the international community to justify far-reaching interventions into the domestic affairs of aid-dependent states. The policy priorities of domestic political actors, the content of new laws, and the workloads of local and national institutions, can readily be coopted to align with international interests and globally-defined human rights agendas.

These dynamics combine to create human rights openings in periods of upheaval that are often absent in contexts where states are stronger or democratic institutions more deeply entrenched. In stable, democratic states, the need to work through preexisting institutions presents something of a “masters tools” problem, in that inequality is often so foundational to the structures that produce oppression in the first place that efforts at redress allow for slow or only partial reform.

Political elites in both DR Congo and South Africa have waxed and waned in their commitments to gender equality. Enduring state weakness in DR Congo offers small – albeit precarious – windows of opportunity for bottom-up and top-down gender mobilisation simultaneously. Domestic activists and international stakeholders have played crucial roles in shaping the content of new laws. And national action plans, supported by international organisations, have ensured the delivery of first-hand gender sensitivity trainings to judges and prosecutors, coordinated trials, and provided direct legal and material resources to courts, police and victims in rape cases. As a result, high numbers of men accused of sexual and gender-based crimes have been charged and prosecuted in the country’s eastern courts.

South Africa’s transition to democracy saw similar openings. Women’s rights activists were integral to the anti-apartheid movement, meaning that women’s and human rights actors who later came to comprise the country’s governing elite were uniquely positioned to influence law and policy. The country was among the first in the world to legalise same-sex marriage, among a host of other pioneering reforms. Yet in the years since transition, gender activists’ influence has waned. Advocates for women’s rights increasingly occupy spaces outside of government, lobbying for, rather than leading, reform. While they continue to pressure government and support victims, they exert far less influence over the day-to-day of justice sector administration than their counterparts in DR Congo.

The promises and pitfalls of opportunity

As opportunities to shape legal processes in DR Congo remain open, those in South Africa have slowly closed. But using state weakness to promote gender reform has come at a cost.

As we observe in South Africa, gains won in periods of upheaval can be fleeting, as the growth and consolidation of state power can result in a backlash against women’s rights and the revitalisation of patriarchy. For states designated as “weak”, however, international involvement may serve to marginalize those whose demands do not align with transnational agendas and stifle alternative forms of political mobilisation. Pathologies of aid and development ensure a focus on externally-defined and globally salient “problems” that fail to respond to locally articulated needs. Moreover, donor emphasis on a single human rights issue (gender violence), and one particular policy response (criminal prosecution), compels victims of myriad injustices to express their needs in the language of law in order to be heard. And all the while, many women remain disappointed by what they have been promised, as enduring state weakness prevents episodic or precarious gains in one realm from spilling over into others.

That is not to say; however, that rights’ struggles in transitional periods have been meaningless. Nor is it to say that legal victories claimed by international actors in DR Congo have not also been wrought from below. Many activists I interviewed had campaigned for years to see violence against women taken seriously by the state and claimed the 2006 law as a significant victory in their struggles for legal rights. Others expressed validation at having the violence they suffered formally recognised as criminal and unjust. Others still have used the changing socio-legal landscape to reap material assistance from NGOs. And many more have deployed the language of law and human rights instrumentally to claim space and power previously denied to them in public and private spheres.

Who benefits?

Feminist scholars of international relations have called attention to the ways in which conventional understandings of both “stateness” and “security” serve to obscure the specific concerns of women and other marginalised groups. While states may appear “peaceful” on paper, it rarely means women are free from violence. And specific populations remain vulnerable, even when states are deemed strong or secure by conventional measures. For states home to a comparably robust democratic apparatus, therefore, state-centric evaluations of peace and security obscure the lived experiences of those at risk of specifically gendered harms. Examining DR Congo and South Africa side by side exposes the windows of opportunity engendered by upheaval or transition, and the subsequent closure of those spaces (and with it a reconsolidation of patriarchal power) as those moments settle.

So when do rights gains born out of transition and upheaval endure? Which women benefit from the availability of new rights and which women remain cut off or marginalised in their realisation? And under what conditions do rights-based struggles extend beyond salient social, political, ethnic or class divides to deliver lasting and intersectional peace for women and men? These questions form the basis of my new comparative project with Marie Berry. We build on our earlier work to evaluate when gender reforms born in periods of upheaval and transition prove capable of contributing to peace and security for a broad cross-section of women. And we suggest that reforms undertaken in the name of gender equality have a weaker chance of contributing to durable peace if access to new rights is determined by conflict-era identity cleavages.

While periods of upheaval are necessarily limited in what they can deliver (and often create space for new forms of violence alongside opportunity), disregarding the terrain on which rights struggles are fought in such moments risks obscuring the foundations from which further dynamics of peace and violence might stem. It is the innovative local responses to intervention and reform, therefore, rather than any legal developments themselves, that will determine future trajectories of social change. Understanding the ways in which access unfolds at the margins – particularly with regard to who can benefit from new rights – holds key insights for what is to follow, and for the reach, depth and durability of intersectional gender reform.

Dr Milli Lake (@MilliLake) is Assistant Professor in the LSE Department of International Relations.

This post first appeared on the LSE's Africa @ LSE blog.