A Tale of Tech Giants, Tax Dwarfs and Sovereigns

Juergen Braunstein and Marion Laboure explore what countries moving to tax the tech giants could do next.

Under Austria’s presidency the EU is stepping up plans for an EU wide digital tax on tech giants, such as Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon. These moves have been championed especially by large consumer countries, such as France and Spain. The prospects of such a digital tax have specifically grown with recent EU Commissions proposed a 3% tax on revenues of tech giants with more than €50m revenue in the EU and €750m worldwide. Brussels estimated that this proposal would affect 150 tech giants and would yield as much as €5bn per year.

These represent the first attempts among sovereigns to adjust to fast, and fundamental changes such as the emergence of tech giants and the explosion of peer-to-peer platforms which transform not only business processes, but also the economics and the politics of taxation.

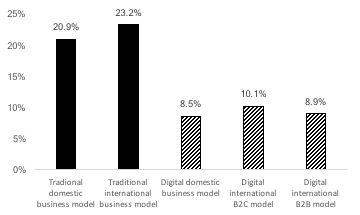

Until recently, a company’s tax base was established according to headquarters location. Multinationals have tended to pay lower taxes than small and medium enterprises (SMEs) on average. The European commission’s report “A Fair and Efficient Tax System in the European Union for the Digital Single Market“, published in 2017, reveals that digital businesses are paying an effective tax rate about half that of traditional businesses in Europe. As such, traditional international business models pay an effective rate of 23.2% vs 9.5% for their digital counterparts. In a fast-paced, globalized world, location is no longer relevant and new challenges arise.

Effective average tax rate in EU28

Source: Digital Tax Index, 2017, PWC and ZEW.

Peer to peer platforms, such as Alibaba, DiDi Chuxing, Amazon and Airbnb, have consistently grown over recent years, and are often more competitive than their conventional peers since they are excluded from normal taxation systems.

European countries need to start thinking of what to do with digital tax revenues from tech multinationals. Then the question would be spending or saving? Governments in power have strong incentives to use this money in a way that supports their re-election. This issue is particularly acute in the context of number of elections ahead in Europe, notably Greek’s parliamentary elections.

The United Kingdom was already confronted with a situation of windfall tax revenues during the 1970s North Sea oil boom. Instead of saving the money (e.g. for future generations) the UK government just spent it.

Rather than using this money to pay off debt, why not allocate it to a sovereign wealth fund, use it for future generations, or seed funding. The UK should have followed the Norwegian model instead. During the 1990s oil boom Norway used it as an opportunity and has now accumulated nearly 1 trillion US in its sovereign wealth fund (SWF) the Pension Fund Global.

Following Singapore? One way would be to follow Singapore in creating sovereign venture funds. Singapore’s largest sovereign venture fund Vertex has a mandate of seeding and developing new business opportunities in areas which are promising for growth. Vertex has a focus on financing growth through specialist venture funds, such as Vertex Asia Fund Pte. Ltd, Vertex China Chemicals, Vertex Technology Fund (III) Ltd. It contributes to Singapore’s role as the regional hub for startup financing and financing the regional expansion of home-grown companies. Investments focusing on software, internet and media sector include firms such as eG Innovations, GrabTaxi, muvee Technologies, or Paktor. The proliferation of sovereign venture funds comes along with Singapore’s long term strategy to establish Singapore as a startup financing and technology hub in Asia.

Following Luxembourg? The idea of using a part of tax revenues for future generations has been promoted by the current government, the Bettel–Schneider ministry (a coalition between the Democratic Party (DP), the Luxembourg Socialist Workers’ Party (LSAP), and The Greens), of Luxembourg, which set up in the 2015 budget a “Wealth Fund for intergenerational generations”. The aim is thus to gather at least EUR 50 mn per year from e-commerce VAT and a residual part from excise duties and to reach EUR 1 bn. Following the example of Norway, one can observe how a country, through a sovereign wealth fund, may turn non-renewable resources, specifically its deposits of oil in diversified financial assets for future generations. In this spirit, the government intends to use to fund future sovereign Luxembourg non-recurrent revenue.

Whether the digital tax will in effect be implemented remains uncertain, and even more uncertainty exists around how these potential revenues will be used. How to spend it without creating new risks? Will it run automatically into the budget?

Image credit: Jonathan Cutrer via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)