Sex Trafficking and Hotels: Why there is a Need for Effective Corporate Social Responsibility

This is part of a forthcoming Global Policy e-book on modern slavery. Contributions from leading experts highlighting practical and theoretical issues surrounding the persistence of slavery, human trafficking and forced labour are being serialised here over the coming months.

Hotels are locations frequently used by sex traffickers to exploit their victims with relative anonymity. A lack of accountability within the hospitality sector has allowed human trafficking to occur in the facilities of many different hotel franchises in the United States as well as at privately owned establishments. Changes in hospitality industry policy in regards to human trafficking are occurring, in part, as a result of numerous civil suits filed by sex trafficking victims in over twenty US federal jurisdictions since 2015. These cases are revealing that previous voluntary actions by the hotel sector were not enough to counter the abuse described in the victims’ suits, which reveal serious misconduct by hotel employees including front desk managers, housekeeping personnel and other hotel staff.

Federal legislation enacted in 2008 allowed entities that facilitate any form of human trafficking to be sued. But this element of the human trafficking law was not widely used by victims of sex trafficking legislation until recently when hotels and hotel chains became the most common entities to be sued by sex trafficking victims, according to the Human Trafficking Institute’s 2020 Federal Human Trafficking Report. Between 2018 and 2020, the percentage of federal civil human trafficking cases involving sex trafficking increased from 12.1% in 2018 to 45.5% in 2020. In 2019 and 2020 alone, federal civil sex trafficking cases were filed against over 400 defendants, including 189 hotels. There is ample reason that hotels were so visible in the civil suits. According to the Human Trafficking Institute, ‘in 77% of active [criminal] sex trafficking cases involving a completed sex act, a sex act occurred at a hotel’. In comparison, only 4% of forced labour civil cases involved the hospitality industry.

Some analysts suggest that increased civil action against corporate entities could reflect a new method for victims to receive payment for damages from businesses which have allegedly facilitated sex trafficking as there is a low rate of mandatory restitution in criminal court. Some of these suits are not only motivated by money. Plaintiffs have used the civil remedy as a legal tool to force accountability and behavioural change in the hotel sector.

Background

Civil remedies were made available to victims of human trafficking in the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2003 and expanded in the TVPRA of 2008. The TVPRA of 2008 allows victims to file a case in US District Court against ‘whoever knowingly benefits, financially or by receiving anything of value from participation in a venture which that person knew or should have known has engaged in an act in violation of this chapter’. The term in the law that a defendant ‘knew or should have known’ has allowed multiple cases to survive the initial motions to dismiss filed by lawyers representing hotel entities. Despite this expansion of the law in 2008, the first federal civil sex trafficking case against a hotel entity was not filed until 2015, revealing the extended length of time it took to use the legislation against the hospitality industry.

Once one case was initiated against a hotel entity, others followed. Within a few years the number of federal sex trafficking lawsuits against the hospitality industry grew exponentially. In 2019, civil sex trafficking lawsuits were filed against 117 hotel defendants around the country, many of which were large chains and industry leaders. The number declined slightly in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, with civil plaintiffs suing 72 hotel defendants.

Rather than suing only the managers of private hotel/motel establishments, many lawyers of human trafficking victims sued hotel franchisee owners and operators, brand managers, and parent companies of big-name hotel chains.

The hotel defendants which have been named in the most civil lawsuits, including Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Choice Hotels International, Marriott, and G6 Hospitality (as seen in Figure I) have all released statements in the past ten years describing policies to prevent human trafficking at their facilities. These strategies rely heavily on employee training, but lack concrete plans for implementation, and many do not openly address employee participation and facilitation of trafficking. Many do not provide explicit whistle-blower protections for employees who report human trafficking on their premises.

The data below is based on the researchers’ analysis of the 43 federal civil sex trafficking cases filed against hotel entities between 2015 and 2020, utilizing data provided by the Human Trafficking Institute. The researchers reviewed the civil complaints for each case, which identify the locations of hotels where trafficking allegedly occurred and the role allegedly played by hotel actors according to trafficking victims.

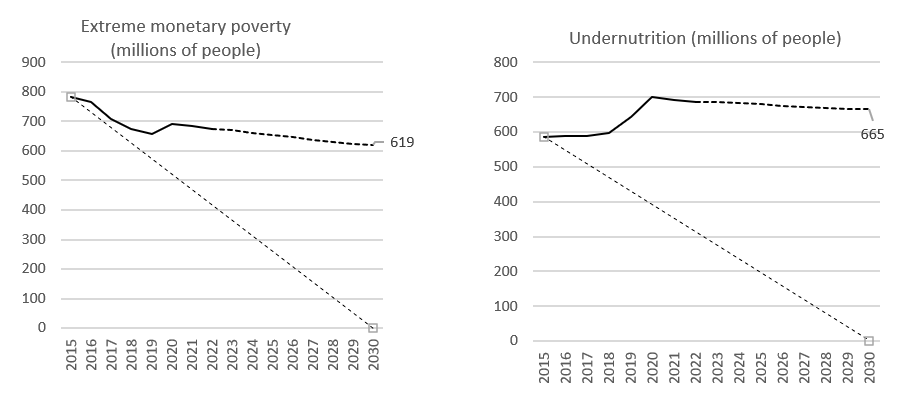

The charts below reveal the key entities sued as facilitators of human trafficking (Figure 1) and the most common hotel brands identified as locations of sex trafficking in civil complaints (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

There is a high correlation between the hotels named in federal criminal cases and in the hotel chains named as defendants in civil lawsuits. The most common hotels in active criminal court cases in 2020 were Motel 6, Super 8, Days Inn, Red Roof Inn, and La Quinta, all of which are visible in Figure 2. Super 8, Motel 6, Days Inn, and Red Roof Inn were also the most frequently identified hotels in criminal cases in 2018 and 2019, excluding small chain and non-chain hotels.

Cases move slowly through the federal courts. Therefore, few cases involving the hospitality sector have been concluded in the federal system. One notable case that has settled had very special circumstances regarding involvement of the victim’s traffickers. In August 2020, Marriott reached an undisclosed settlement with a plaintiff in a Pennsylvania federal court case after the judge allowed Marriott to file claims against the plaintiff’s alleged traffickers as third party defendants, causing the victim to ‘fear for her safety’.

Civil courts at the state level have also been used to address the crime of human trafficking as the following case was filed by the City Attorney of Los Angeles in a nuisance abatement lawsuit. In 2017, G6 Hospitality paid a $250,000 settlement in Los Angeles after the City Attorney sued the owners of one Motel 6 property in Sylmar over concerns of gang activity, drug dealing, and prostitution.

Facilitation of Sex Trafficking in Hotels

Examination of the federal civil case files from 2015 to 2020 detail different ways that hospitality sector employees facilitate human trafficking. Hotel workers are described as witnesses to sex trafficking which they failed to report. Moreover, some hotel employees not only failed to report obvious signs of trafficking, but also cooperated directly with traffickers by working as lookouts, reserving specific rooms, and accepting bribes in the form of cash, drugs, or sex with victims. For instance, one California case was filed in 2020 against multiple hotel chains including Wyndham and G6 Hospitality. The plaintiff claimed that beginning in 2014 employees at a Super 8 motel accepted cash payments from her trafficker to work as police lookouts, and one Motel 6 employee took cash bribes in exchange for booking a room towards the back entrance of the motel (B.M. v. Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc. et al).

Several plaintiffs claim that traffickers and front desk employees developed a close relationship which hindered victims’ efforts to escape. For example, at the Days Inn in Hampton, Virginia in 2012, the victim A.D. managed to escape her trafficker after being violently beaten, but ‘knowing that the hotel staff was too involved with her trafficker’, she chose to run to the nearest gas station rather than solicit help from the hotel employees (A.D. v. Wyndham Hotels and Resorts). Another victim claimed that while being trafficked out of a Motel 6 in Albany for over a month, she would frequently call for help from inside the motel room. On multiple occasions hotel employees allegedly came to the door to stop the yelling, but took no action in reporting the incidents (V.G. v. G6 Hospitality, LLC).

At one Quality Inn in Cincinnati, Ohio, it was ‘a common practice’ that the entire top floor of the hotel was rented out to pimps for an extra cash fee at the front desk (A.C. v. Red Roof Inns Inc. et al). One Georgia case described a similar arrangement in an Atlanta Microtel (a Wyndham brand). One trafficker allegedly controlled the entire third floor for several years, paying the front desk employees in drugs or money to serve as lookouts for police activity (Jane Doe 1 v. Red Roof Inns et al). The same case identified a Ramada Inn in Alpharetta, GA with a similar modus operandi. Two employees worked as lookouts for the trafficker, following an agreement that both hotel employees would have sex with the victim each day she was exploited at the hotel where they worked.

Multiple plaintiffs claim that hotel employees, including housekeeping staff and front desk workers, witnessed these indicators of sex trafficking and did not report them, thereby acting as facilitators even if they did not actively cooperate with the trafficker (A.D. v. Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc; A.T. v. Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc.; S.J. v. Choice Hotels Corporation; H.M. v. Red Lion Hotels Corporation). These alleged actions by hotel staff highlight the importance not only of training, but of empowering lower income staff members to report the activities of employees in more powerful positions without facing retaliation from their employers. Along with the red flags listed above, often victims were seen walking around hotel hallways with visible injuries, and hotel rooms were left stained with the victim’s blood after violent physical and sexual assault (S.Y. et al v. Naples Hotel Company et al). In similar instances at two motels—a Motel 6 and one Super 8 in Columbus, Ohio in 2015—a victim was allegedly found by housekeeping staff members tied up in her hotel room and pleading for help, but the employees took no action (H.H. v. G6 Hospitality LLC et al). Similarly, one plaintiff claimed that the housekeeping staff saw her sheets ‘covered in blood’ after a particularly violent sexual assault, but nothing was done to help her (A.T. v. Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc.).

Technology has been a key facilitator of human trafficking and many tech companies are now also being sued by human trafficking victims (P.H. v. Salesforce; Doe v. MailChimp; Hashmi v. HCL America). Their facilitating role in human trafficking in hotels is also apparent in the federal cases filed. Automated hotel check-ins, check-outs and online reservation systems are technologies which ‘limit interaction between hotel staff members and guests -- thereby curtailing potential points of identification and interaction’ of human trafficking. Hotel amenities such as computers and WiFi were repeatedly used by traffickers to upload advertisements soliciting buyers for sex on web pages such as Backpage, Bedpage, CityXGuide, and Craigslist (E.B. v. Howard Johnson by Wyndham Newark; A.D. v. Wyndham Hotels and Resorts). In the previously mentioned Atlanta Microtel case, the victim’s trafficker allegedly used the hotel computer, visible to employees from the hotel lobby, to update advertisements for sex with the victim exploited at their hotel (Jane Doe 1 v. Red Roof Inns et al).

Parent Companies and Corporate Responsibility

Many corporations in the hospitality sector now espouse their commitment to corporate social responsibility, including countering human trafficking. But despite these new commitments, some alleged and identified cases of exploitation have occurred after major hotel chains adopted anti-trafficking guidelines and training programs. The allegations made by plaintiffs in these civil sex trafficking cases against hotels show a significant disconnect between the anti-trafficking policy publicized by the hospitality parent companies and the implementation of that policy.

Examination of the civil cases filed in federal courts suggest that the introduction of corporate policies to prevent human trafficking is not sufficient if the policies are not matched with internal oversight, and regular assessment of policy implementation and effectiveness. As Figures 1 and 2 show, persistently high rates of sex trafficking are associated with certain brands and franchises. This suggests the lack of prioritization of efforts to combat human trafficking, and poor implementation of policy and training.

For instance, one victim who sued a Red Roof Inn in Smyrna, Georgia stated that the hotel chain had a policy that if housekeeping was denied for three days, the room should be entered and inspected. The policy was not followed, and the victim’s hotel room was not visited by the housekeeping staff for weeks at a time (Jane Doe 1 v. Red Roof Inns, Inc.).

Many red flags of human trafficking which have been publicized by ECPAT-USA (End Child Prostitution and Trafficking) and the Department of Homeland Security were allegedly seen and ignored by hotel staff in the cases examined. They include, but are not limited to, the use of cash or prepaid credit card payments to pay for rooms, lack of personal possessions or luggage, multiple unregistered guests visiting for a short period, and frequent requests for clean linens and towels. These signs should be part of any training program and policies must be in place to insure that hotel employees identifying such behavior respond in an appropriate manner.

Corporate Reluctance to Address Human Trafficking

There are diverse reasons that companies have been reluctant to introduce policies against human trafficking. Some refused to recognize the ubiquity of the problem. For others, it could be a product of corporate fear that consumers would associate franchised brands with sexual exploitation. Some were more concerned with keeping rooms occupied than addressing the exploitation occurring within the rooms. Some franchisees knew that customers sought to bring prostitutes to their rooms and oversight of this would be bad for business. Therefore, they were conforming to Leary‘s insight that ‘[human trafficking] is so profitable that legitimate businesses that benefit from it – or from the structures that allow it to thrive – are willing to tolerate it.’ Moreover, some corporations in the hospitality sector did not want to taint their reputations by engaging with the problem of human trafficking. Therefore, the reluctance was multi-faceted motivated by finances, reputation and in some cases ignorance or wilful blindness.

Certain high profile investment firms connected to the hospitality industry have been positively recognized for their commitment to ESG principles, despite their lack of company-wide standards against human trafficking. The Motel 6 brand is owned by Blackstone, one of the world’s largest investment management companies, which has openly endorsed environmental sustainability and workplace diversity and inclusion. Despite embracing certain aspects of corporate responsibility, the firm has neither addressed the human trafficking occurring on its properties nor encouraged anti-trafficking procedures across its company portfolio.

Certain companies have adopted more robust anti-trafficking ESG policies in recent years, and some have attributed this shift to Marriott’s well-received 2017 decision to require employee human trafficking training at all owned and franchised locations. Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Choice Hotels, Marriott, and G6 Hospitality (all included in Figure I) have all publicized partnerships with the anti-trafficking organization ECPAT to demonstrate their corporate commitment to fight human trafficking. ECPAT hosts a voluntary initiative known as ‘The Code’ which consists of six criteria, including the adoption of anti-trafficking policies and procedures, which companies must adhere to in order to gain membership. Attorneys representing sex trafficking victims in civil court have cited these partnerships as evidence that hotel defendants were aware of the problem of human trafficking, but in practice showed a ‘willful blindness’ for the sake of profit (A.C. v. Red Roof Inns). Examination of ECPAT’s website for hotel conformity with these core elements of their checklist shows a generally low level of compliance.

According to a 2019 report from ECPAT-USA which compared the progress of various travel industry sectors in combating human trafficking, the franchised hospitality sector scored 70% in the adoption of policies and procedures against trafficking, which was the highest rating among all sectors. However, franchised hospitality fell behind aviation and travel management companies in policy implementation, and scored below the overall industry average on the inclusion of child sex trafficking in relevant contracts and subcontracts.

Conclusion

Corporate competition, brand reputation, and the threat of suits have motivated many companies in the hospitality sector to adopt anti-trafficking policy. Unfortunately, there has been more focus on the adoption of policies and less on their effective implementation. The need for better policy implementation is also made apparent by weak employee training requirements among many signatories of The Code. As late as 2019, neither Wyndham nor Choice Hotels mandated employee training as a requirement for franchisees. Despite this, employees across the industry are expected to bear the burden of identifying trafficking and act as the ‘eyes and ears' of the hospitality industry, and several companies provide confidential hotlines for employees to report unethical behavior. Yet the hospitality response is still placed heavily on employees in potentially vulnerable positions who are rarely protected by whistleblower policies.

Hotels and motels outside of the United States are also vulnerable to sex trafficking. Many of the hotels cited in US federal criminal and civil cases operate globally and manage or franchise hotels internationally. Therefore, these problems discussed are not confined to the United States. Research in Europe also identifies the critical role of hotels in the crime of sex trafficking. In his 2020 analysis of the role of European hotels in human trafficking, Paraskevas argues that the lack of centralization as well as property diversity in the hotel sector ‘make hotels more attractive for traffickers and perhaps easier for rogue hoteliers to profit’ from exploitation related to trafficking.

The research conducted for this paper suggests that the problem of hotel-facilitation of human trafficking is more endemic a problem internationally than merely that of rogue hotels. The absence of effective training for hotel employees and of protections for whistleblowing by employees of some of the world’s major hotel chains suggests that this problem is more endemic than recognized. Internationally, many employees of the hospitality sector are at the low end of the social and economic sector, and therefore without adequate protections from their employers they may wittingly and unwittingly facilitate human trafficking.

American federal cases provide a window into the facilitating role of the hotel sector that is not readily available elsewhere. The defendants in the civil cases examined include hotel management companies, property owners, and facilities service companies, reflecting the highly diversified supply chain of the hospitality sector. Therefore, in the United States as well as on a global scale, anti-trafficking efforts require the coordination of properties and organizations across diverse regions, territorial borders, and business types to address the key role of this sector in enabling human trafficking.

Corporate social responsibility, if properly implemented in the hospitality sector, could increase both the risks and costs of trafficking, and act as a deterrent. It could provide greater access to justice for many victims of trafficking who often are very vulnerable as many are minors, minorities and socially and economically disadvantaged.

As a 2018 Polaris report on human trafficking within the hospitality industry stated, simply adopting policy is ‘not enough’ if the policy is not enforced and implemented on all levels of employment. In order to produce a lasting change in the industry, these adopted policies must be matched with internal accountability and effective training, with well communicated protections for vulnerable employees. This has yet to occur.

As the tools against trafficking continue to develop, the application of civil remedies against hotels provides one more avenue for survivors to hold facilitators accountable and help influence industry-wide change. The judicial outcome of the majority of these cases is yet to be seen, but the allegations of the court documents clearly indicate the vital roles that corporate negligence, complicity, and employee participation play in facilitating sex trafficking.

Sarah Meo is a PhD student in Public Policy at George Mason University’s Schar School. Her research focuses on transnational organized crime, corruption, and human trafficking. Prior to George Mason University, she received her Masters of Advanced Study (MAS) in Criminology, Law and Society from the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Louise Shelley is the Omer L. and Nancy Hirst Endowed Chair and a University Professor at George Mason University. She is in the Schar School of Policy and Government and directs the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center (TraCCC) that she founded. She is the author of Human Trafficking: A Global Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and many other works.

This research was funded by National Science Foundation, EAGER: ISN: A New Multi-Layered Network Approach for Improving the Detection of Human Trafficking, grant number CMMI-1837881.

Photo by Thgusstavo Santana from Pexels