A Pragmatic and Humanist Approach to Refugees and Migrants – A conversation with Helidah Ogude

Helidah Ogude, Social Development Specialist at World Bank in Washington, DC, explores the impact refugees have on the host countries, the approach towards migrants and the role of language we use talking about newcomers.

- Your research work investigates the impact that refugees/migrants have in host countries. What are some of the common themes that you have come across and can you tell us which countries/regions you are working on?

The long-term impacts that refugees, in particular, have on host countries is a generally under-researched topic, although this has changed over the last few years given the war in Syria. So some research has emerged out of major host countries like Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. Generally, research shows that over time and on aggregate, migrants/refugees have a positive impact on the economy – especially if they are allowed to legally work and social protection mechanisms are put in place for the most vulnerable in the host country. In the short term they tend to have a differentiated impact, so for instance, they may have a positive impact for those that own property or are wealthy in that economy but may negatively affect the unskilled or very poor. In any context, a large number of people suddenly entering an environment puts a strain on services like health, housing and education – so this is really where a lot of investment to expand these services and maintain quality needs to be invested. What we have also found is that cities and towns are often at the forefront of dealing with the presence of migrants/refugees, and this is also where funds and human capital needs to be channeled, and area-based programs - which don’t discriminate against who is in that area - need to be implemented. The reality is that refugees often live in areas where there are already poor hosts, so area-based interventions serve both the poor hosts and the refugees.

- Some countries, you said, are planning on using World Bank concessional funds to provide, for instance, all refugees children access to local schools, access to their health insurance system, and local job market? How is this received by locals in those countries that may not have such access for their own children?

This is a really important question. The World Bank, unlike humanitarian organizations like the UNHCR, is focussed on the long-term development of a country. For instance, the UNHCR was established to deal with emergencies, not the long-term stay of refugees in camps. However, many conflicts these days are protracted and this means that refugees are, on average, staying in host countries for 24 years. This means that integration, as oppose to voluntary return or repatriation is increasingly becoming a reality that host governments need to face. Socio-economic integration of refugees affects locals in terms of social cohesion, access to jobs, schools etc. So many of the projects where the Bank provides concessional loans or grants, include local actors. It’s not desirable, ethical or sustainable to have refugees accessing services in the same village where locals don’t, for example.

This is a really important question. The World Bank, unlike humanitarian organizations like the UNHCR, is focussed on the long-term development of a country. For instance, the UNHCR was established to deal with emergencies, not the long-term stay of refugees in camps. However, many conflicts these days are protracted and this means that refugees are, on average, staying in host countries for 24 years. This means that integration, as oppose to voluntary return or repatriation is increasingly becoming a reality that host governments need to face. Socio-economic integration of refugees affects locals in terms of social cohesion, access to jobs, schools etc. So many of the projects where the Bank provides concessional loans or grants, include local actors. It’s not desirable, ethical or sustainable to have refugees accessing services in the same village where locals don’t, for example.

- Across Europe, the US, and other parts of the world, we hear a lot about the “inherent risks” refuges present to a country/community. How does your work address this issue?

Our work tries to, in part, use research to complicate often reductive and unsubstantiated claims. Our research tends to show more complex results and we try to use this research to then inform policies that protect vulnerable host communities where necessary, but also recognize that refugees are more than “refugees” – they are women, teachers, etc. – they have skills and cultural contributions to make to the societies where they find themselves. In a sense, the research can act as a common set of information around which discussions can be had, as oppose to the selective use of misinformation by various people.

- What you do is research and, inevitably, this has to come face-to-face with the lived experiences and perceptions that locals on the ground will have, especially on the topic of refugees and migrants. How do you bridge this gap with the research work and lived experience do not necessarily cohere?

This is also an important challenge. It highlights the limits of certain types of research. We can do research that finds that migrants have a positive impact on an economy, but if your research doesn’t account for the social and political dynamics of the context, the research can easily be rendered irrelevant. It often comes down to understanding what informs people’s perceptions, what the political incentives are, and what conditions people live in on a day to day basis. This helps one frame research in a humane and realistic manner. In a manner that doesn’t discount the grave conditions in which many local and migrants live in but in a manner that also highlights the positive political value of considering that research. It’s a delicate and difficult balance to strike.

- We see how refugees/migrants are being instrumentalized for political objectives. For example, president Trump called the caravan of people coming toward the U.S. border, “an invasion”, and in Europe similar rhetoric and language is used by far-right political parties. How is the use of such language influencing policy towards refugees/migrants?

The language we use to describe people or phenomena is extremely important. Especially in the rapid technological context we live in, language travels. But language is not mere words, language can incite certain actions. So for example, to call someone “illegal”, then means that the requisite remedy is to criminalize them, to arrest them. How migrants are depicted also illuminates popular anxieties about the foreigner as an “invader” and perhaps more importantly, provides clues to what are deemed the appropriate political responses to address these anxieties. In a sense, one could argue that to de-humanize (and in fact in many cases strip people of any human quality altogether), for example to describe refugees as pathogens or rats like has been done in mainstream media in Europe, the US and other places, then enables a treatment of them as such. They then need to be eradicated or exterminated, like one would a pathogen. I’d also add that it’s not only those on the right or extreme politics that are using this language. We’re increasingly seeing problematic language being adopted by centrists and others on the political spectrum because they see that it works with right-wing constituents. So I think it is incumbent on all of us to be careful about the language we use, not to uncritically appropriate certain terms, not to normalize certain discourse. Because to do so makes it easier for those terms to gain meaning in policy documents and to influence actions that affect people’s lives.

Helidah Ogude is a Social Development Specialist at World Bank in Washington, DC. She is Global Governance Futures 2030 fellow. The views expressed here are her own.

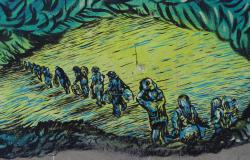

Image credit: Jeanne Menjoulet via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)