The Decline of the Labour Share of Income

What’s at stake: at odds with the conventional wisdom of constant factor shares, the portion of national income accruing to labour has been trending downward in the last three decades. This phenomenon has been linked to globalisation as well as to the change in the technological landscape - particularly “robotisation”. We review the recent literature on this issue.

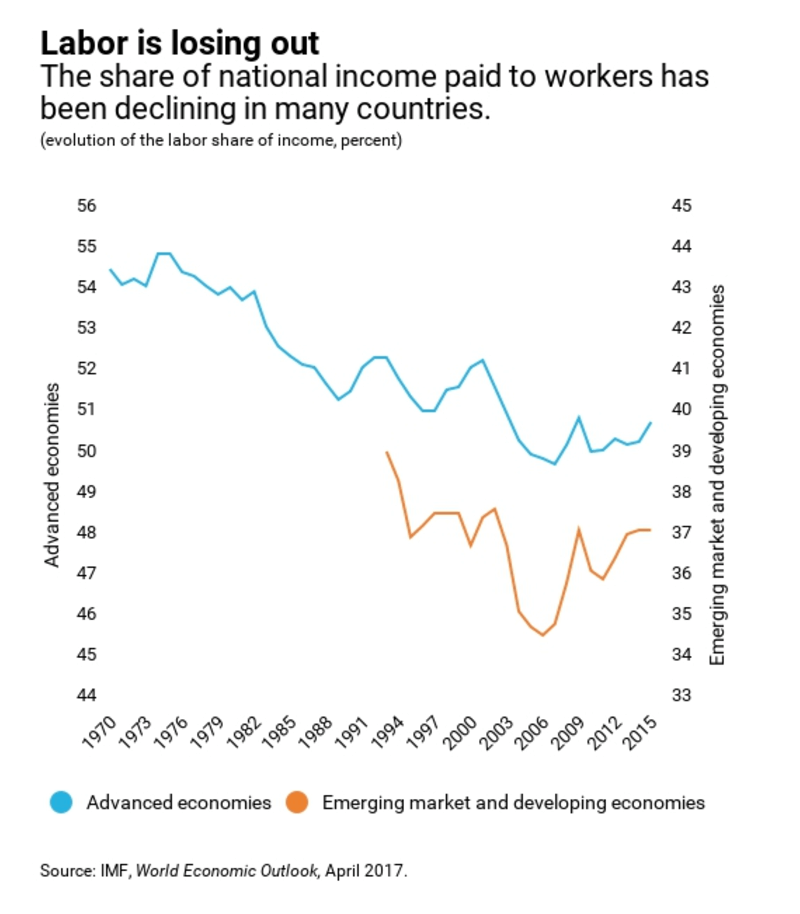

Chapter 3 of the IMF’s 2017 WEO documents the downward trend in the labour share of income since the early 1990s, as well as its heterogeneous evolution across countries, industries, and workers of different skill groups. In advanced economies, labour income shares began trending down in the 1980s, reached their lowest level just prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, and have not recovered materially since. Labour income shares now are almost 4 percentage points lower than they were in 1970.

According to the IMF’s analysis, In advanced economies about half of the decline in labour shares can be traced to the impact of technology – a combination of rapid progress in information and telecommunication, and a high share of occupations that could be easily be automated. Global integration – as captured by trends in final goods trade, participation in global value chains, and foreign direct investment – also played a role, but its contribution is estimated at about half that of technology. The decline in labour shares in advanced economies has been particularly sharp for middle-skilled labour. Routine-biased technology has taken over many of the tasks performed by these workers, contributing to job polarization toward high-skilled and low-skilled occupations.

The OECD also wonders whether the labour share of income has declined, and answers that it depends on whether you measure it using a production- or income-based approach. The former adopts a producer perspective with gross income as a reference. The latter adopts a consumer perspective with net income as a reference, taking account of depreciation and including taxes and subsidies as perceived by final consumers. Using the production perspective, the OECD can confirm a statistically significant but small decline in the labour share across OECD countries over the past two decades. But this appears to result mainly from a rise in the gross capital share caused by rising depreciation rates. Accordingly, there is little or no decline in the labour share from an income perspective, where income is measured net and after depreciation.

David Autor et al. build a “superstar firm” model where industries are increasingly characterized by “winner take most” competition, leading a small number of highly profitable (and low labour share) firms to command growing market share. They evaluate and confirm two core claims of the superstar firm hypothesis: the concentration of sales among firms within industries has risen across much of the private sector; and industries with larger increases in concentration exhibit a larger decline in labour’s share

Matthias Kehrig and Nicolas Vincent look specifically at the micro-level anatomy of the aggregate labour share decline in U.S. manufacturing, which declined from 67% to 47% of value added over the last three decades. This seems at odds with the fact that the labour share of the typical U.S. manufacturing plants, in contrast, rose by over 5 percentage points. They argue that the two facts can be reconciled by considering: (i) an important reallocation of production towards “hyper-productive plants” and (ii) a downward adjustment of the labour share of those same plants over time. Relative to their peers, plants that account for the majority of production by the late 2000’s arrive at a low labour share by gradually increasing value added while keeping employment and compensation unchanged.

Elsby et al. also look at the evolution of the labour’s share of income in the United States, reaching 5 conclusions. five conclusions. First, about a third of the decline in the published labour share appears to be an artifact of statistical procedures used to impute the labour income of the self-employed that underlies the headline measure. Second, movements in labour’s share are not solely a feature of recent U.S. history: the relative stability of the aggregate labour share prior to the 1980s in fact veiled substantial, though offsetting, movements in labour shares within industries. By contrast, the recent decline has been dominated by the trade and manufacturing sectors. Third, U.S. data provide limited support for neoclassical explanations based on the substitution of capital for (unskilled) labour to exploit technical change embodied in new capital goods. Fourth, prima facie evidence for institutional explanations based on the decline in unionization is inconclusive. Finally, our analysis identifies offshoring of the labour-intensive component of the U.S. supply chain as a leading potential explanation of the decline in the U.S. labour share over the past 25 years

Petra Dünhaupt links the decline in the labour share of income to the increase in financialisation. The increasing importance of the financial sector had an impact on the distribution between wages and profits, on the one hand, and retained earnings and financial income in the form of dividends and interests, on the other hand. Using a time-series cross-sectional dataset of 13 countries over the time period from 1986 until 2007 she finds a relationship between increasing dividend and interest payments of non-financial corporations and the decline of the share of wages in national income.

Doan and Wan concentrate on exploring the role of globalization in driving the labour share. In particular, they focus on the impacts of trade openness and foreign direct investments (FDI) using country-level panel data for 1980–2010, and study finds that trade is a significant and robust determinant of labour share. Generally speaking, export depresses while import increases the labour share. The impact of FDI, however, is insignificant. These results are similar for both developed and developing countries.

Jacobson and Occhino look at the relationship between the decline in labour income and inequality. Since labour income is more evenly distributed across U.S. households than capital income, the decline made total income less evenly distributed and more concentrated at the top of the distribution, and this contributed to increased income inequality. The Gini index increases by approximately 0.15 to 0.33 percentage points for every percentage point decline in the labour share. Given these numbers, the decline that the labour share has experienced since the early 1980s (3 to 8 percentage points depending on the measure) translates into an increase of the Gini index of up to 2.5 percentage points.

Young and Tackett look at 125 countries during the 1970–2009 period and explore the relationship between globalization and labour share. They find that economic flows are often negatively related to labour shares, but measures of social globalization tend to be positively related to labour shares. While greater mobility of goods and capital may be associated with increases in capital’s bargaining power, all else equal, greater flows of information, ideas, and people may increase the bargaining power of workers.

Silvia Merler, an Italian citizen, joined Bruegel as Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel in August 2013. Her main research interests include international macro and financial economics, central banking and EU institutions and policy making. This post first appeared on Bruegel's blog.

Photo credit: DonkeyHotey via Foter.com / CC BY