Sustainable finance: the rise of the “E” in ESG

New research tracks the rise of E over S in sustainable finance.

Despite widespread interest in the topic, there is a lack of consensus about what sustainable finance is, and crucially, a paucity of knowledge on how policymakers are engaging with it. The United National Environmental Program traces sustainable finance – as a concept – to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. This sparked the UNEP Finance Initiative, which began with a focus on how the banking sector can facilitate green projects. This flagship of “green banking” has steadily expanded to more areas of the financial sector, as well as encouraging financial actors to consider how degradation of the environment will affect their businesses.

In recent years, the language of environmental, social, and governance (ESG), has come to the fore in finance. This raises the question: has sustainable finance focused on the E, the S, or the G? By using a text-as-data approach to study how public policies around the world address sustainable finance, we find that the “E” – especially “green themed” language – has risen to prominence relative to the socially-focused (e.g., socially-responsible investing) terms.

What language is used in public policy?

We show how the use of ESG in sustainable finance policy has evolved over time by testing a corpus of 1,070 Sustainable Finance Policies (i.e., corporate sustainability policies that target financial activities and institutions to some degree) spanning a period from 2001 to 2021. We conceive of three distinct time periods, each of sufficient length to capture key events that have likely shaped sustainable finance policy.

We start in 2001 with the first appearance of a sustainable finance cognate term in public policy, and run until 2008, the start of the Global Financial Crisis. The second period starts in 2009 with the Copenhagen Summit (now “COP”) and runs to 2015 with the signing of the Paris Treaty. The third period then starts in 2016 and runs to 2021, the final year in which we have policy data.

For each period, we examine the relative frequency of the use of sustainable finance “n-grams” (words or phrases) in our dataset of public policies. This was done using a combination of the Quanteda and tidyverse packages in RStudio. To show the results, we produce a series of word clouds illustrating how sustainable finance policies use E, S, or G language. The larger the term is visualised in the word clouds, the more frequently it is used relative to all other terms used in the same period.

Figure 1 shows a word cloud visualising our first period, spanning 2001-2008. The most frequently used sustainable finance term in this early period is ‘responsible investing’ (27%), followed closely by ‘socially responsible investing’ or SRI (24%), while ‘community investing’ (3%) and ‘ethical investing’ (3%) also feature. ‘Sustainability reporting’ (24%), a ‘G’ term, is also prominent in this period. ‘E’ n-grams in teal, including ‘carbon credit’ (5%) and ‘carbon finance’ (3%) are used far less frequently. Thus, in this earliest period, sustainable finance terminology predominantly corresponds to the “S” and “G”, rather than the “E”.

Figure 1. Sustainable Finance N-grams 2001-2008

Note: The teal font depicts the ‘E’ n-grams, the navy-blue the ‘S’ n-grams.

The contrast with the next period, shown in Figure 2, is striking. Between 2009 and 2015, we see 23 different sustainable finance n-grams in use. While ‘sustainability reporting’ (19%), a governance-focused n-gram, is the dominant term in this period, ‘S’-related n-grams remain prevalent with ‘responsible investing’ (17%), ‘community investing’ (9%) and ‘SRI’ (5%) frequently used. However, it is also in this period that we start to see many ‘E’ terms appearing, including ‘green investing’, ‘green bond’, ‘green credit’, and ‘green finance’, as well as ‘carbon credit’, ‘carbon finance’, ‘carbon tax’, and ‘carbon finance’.

Figure 2. Sustainable Finance N-grams 2009-2015

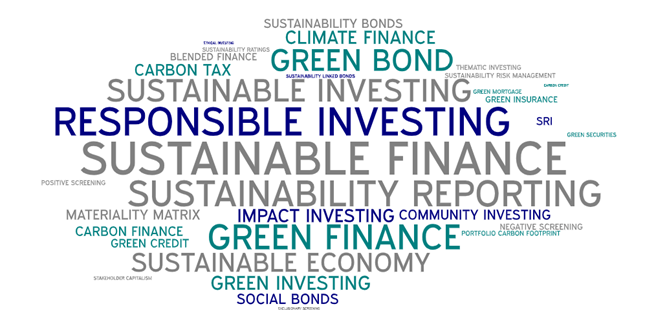

It is in the later period, as shown in Figure 3, that we see a greater concentration of public policies using the language of governance (e.g., reporting, materiality matrix). In contrast, ‘socially responsible investing (SRI)’ falls largely out of use (down to just 1%). In addition, we see more teal words, reflecting the rise of green cognate terms, or the E in ESG, in the form of green bonds, credit and finance as well as carbon credit and tax.

Figure 3. Sustainable Finance N-grams 2016-2021

Relative rise of E over S in sustainable finance

Over time we see an increase in the relative prevalence of n-grams involving ‘green’, ‘carbon’ and ‘climate’ (‘E’ language), with green bond, green finance, green investing, and climate finance all moving from the periphery towards the core of the word cloud. At the same time, other than ‘responsible investing’, the language of social responsibility (‘S’ language) dropped from its previously prominent position. The prominence of ‘E’ n-grams in the latest era suggests the term sustainable finance has gone full circle since its genesis in Rio in 1992. While it originated from an environmental perspective, the language of sustainability appears to have been consumed by that of social responsibility in the early 21st century. We are now seeing the proliferation of ‘climate’ and ‘green’ in public policies pertaining to instruments (e.g., green bonds) for acting on the ‘E’ aspect of sustainable finance.

This shift reflects the finance sector increasingly being seen as vital to mobilizing large amounts of private capital to meet the investment needed for achieving the UN SDGs and the climate targets of the Paris Agreement. Sustainability, in this sense, may increasingly refer to the environment as the priority, subsuming people into planet priorities.

Adam William Chalmers is Senior Lecturer (European Union Politics) at the University of Edinburgh, School of Social and Political Science. His research, which has appeared widely in leading journals like Regulation & Governance, European Journal of Political Research, and Journal of Public Policy, focuses on corporate sustainability policy, corporate lobbying, and natural language processing.

Robyn Klingler-Vidra is Reader in Political Economy at King’s College London. She is the author of The Venture Capital State: The Silicon Valley Model in East Asia (Cornell University Press, 2018) and focuses on entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability.

David Aikman is Professor of Finance and Director of the Qatar Centre for Global Banking and Finance at King’s Business School. His research focuses on central banking and financial regulation and has appeared in the leading peer-reviewed journals including Journal of Economic Perspectives and The Economic Journal.

Karlygash Kuralbayeva is Senior Lecturer in Economics, Department of Political Economy, King’s College London. Her research focuses on climate change policies and environmental regulation and has appeared in the top-field peer-reviewed journals including, Journal of International Economics, and Journal of Environmental Economics and Management.

Timothy Foreman is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Qatar Centre for Global Banking & Finance, King's Business School. He works on research on the impacts of climate change, and how the financial system can contribute to mitigating these effects.