New and Old Power: A Framework to Better Understand and Cultivate Digitally-Mediated Activism

This is the fourth of a four-part Global Policy blog series that seeks to spark new ways of thinking about digitally-mediated activism. It engages Timms and Heimans’ New/Old Power framework as a pivot upon which to interrogate power: asking how activists can use the internet to achieve and challenge new forms of power and ultimately, better make change happen. Read the first here.

This final blog in our four-part series seeks to bring everything together: reflecting on lessons learned from each case study about how best to ‘make change happen’ in contrasting political contexts, and how Timms and Heimans’ New/Old power framework helps us learn from them. Ultimately, we want to answer (as best we can, and without resorting to the academic mantra: ‘it depends’), the two questions we initially outlined:

- First, what is the value of the New/Old power framework in helping us understand contemporary activism?

- Second, how can it help us cultivate the power to ‘make change happen’?

Lesson 1: Epistemic victories matter, even if they’re not tangible

Let’s first remember the context in which this blog was written. As outlined in Blog 1, we initially wanted to interrogate the New/Old power framework due to a limited current understanding of the impact of digitally-mediated activism, with little nuance or caveat. Recognising this, we argue first that the New/Old power framework helps us to understand contemporary activism better (Question 1), by highlighting the value of its intangible impacts.

A theme explored in both Blogs 2 and 3 is the failure of each case study to generate tangible change. For the lay reader, it would be easy to assume, therefore, that both cases of activism have ‘failed’: neither saw the progressive political, legislative or policy change that would resolve their battles, or make them more easily fought in future. What the New/Old power framework shows us instead is the value of the epistemic, intangible victories that New Power-led activism can create, particularly for marginalised communities. In both case studies, activists used social media as a digital site for resistance: one where they could articulate their experience and humanity in ways rarely afforded to them in analogue space. The result, for both marginalised black communities in Flint and pro-choice campaigners in Russia, was an intangible power within, formed through a digitally-enabled restitution of collective identity.

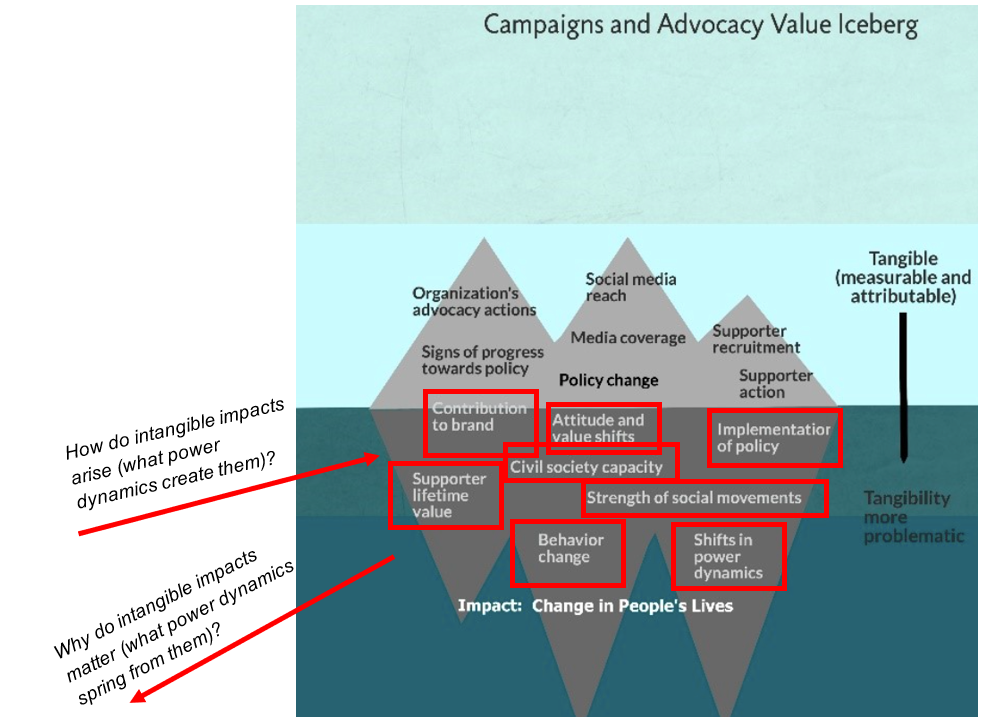

Of course, we should already know that intangible impacts matter - indeed, frameworks such as Schlangen and Coe’s ‘value iceberg’ underline that tangible (policy or legislative) change often forms only the ‘tip of the iceberg’. This helps us to see and name that which cannot be measured or touched - a UV light exposing the invisible fingerprints of ‘influencing’.

Yet what’s missing is an understanding of how intangible impacts happen (what power dynamics get us there) and why intangible impacts matter (what power dynamics might spring from them). The contribution of the New/Old Power framework, then, is to enhance this understanding, by showing us how activism’s intangible impacts arise and what they may achieve. Old Power is tangible (based on capital, land, influence, and connections), while New Power is intangible (diffuse and shared) - yet both have the potential to topple institutions, leaders, and governments when harnessed correctly. More than just existing alongside tangible impacts (as the value iceberg shows), the New/Old power framework shows us instead that intangible impacts are important ends in themselves.

The ‘value iceberg’, created by Jim Coe and Rhonda Schlangen for Better Evaluation (2014). The understanding of intangible impacts of advocacy and campaigning are enhanced by the New/Old Power framework and its focus on power dynamics.

Lesson 2: Epistemic victories can also be an important means to a more tangible end

Beyond this, intangible victories matter in another important way: as important means to a more tangible end. We argue that the individual acts of resistance in the case studies should be seen as significant moments in a broader series of moments: each developing what has come before and breaking ground for what is to come.

This builds on a history replete with examples. Rosa Parks’ defiance of US racial segregation laws in 1955, for example, might have been seen at the time as a symbolic but ultimately ineffective event in the face of a seemingly intractable racial system. What we know now, of course, is that her defiance became one of a series of pivotal acts of civil disobedience that together contributed to the momentum of the civil rights movement.

The New/Old power framework therefore helps us to understand contemporary activism better (Question 1) by drawing our attention to the connection between (intangible) individual acts and (tangible) big-picture change, as driven by activists participating in a ‘New’ peer-driven and participatory movement. No victory in a campaign is too small: every win helps build consensus among the crowd, creates precedence for change, and generates momentum. The fact that activism in Flint and Russia did not lead to tangible change thus becomes irrelevant, overridden by the simple fact of their participation. In both, activism cultivated a first-time base of popular support and broke fresh ground for resistance - staple ingredients for ‘making change happen’.

To counter Gladwell’s contention that ‘the revolution will not be tweeted’, owing to the weak ties associated with digitally-mediated activism, the New/ Old power framework therefore suggests that digital (low-risk) activism does not necessarily lead to low impact. Rather, low-risk individual acts and the (supposedly) weak ties they form remain crucial first steps, paving the way for strong ties, high-risk activism, and ultimately, high rewards.

Lesson 3: To make change happen, we need to go bilingual

Yet, having considered the value of the New/Old power framework in helping us understand contemporary activism (Lessons 1 and 2), there remains one key question: how can it help us cultivate the power to ‘make change happen’? We argue that this relies not on prioritising New power at the expense of Old, but in embracing both, and their complementarity. Timms and Heimans call this ‘going bilingual’: recognising the limitations of ‘New’ power, and utilising the best of ‘Old’.

Step 1: Recognise the limits of New Power

New Power, operating alone, remains characterised by key shortfalls. First, as Blogs 2 and 3 have alluded to, New power movements have struggled to overcome the significant political capital wielded by Old power organisations - EG?

Added to this are countless examples in recent years of movements based on New Power models and values that have failed as a result. Occupy Wall Street, for example, has been described as a “movement constrained by its own contradictions: filled with leaders who declared themselves leaderless”. In this example, and many others, diffuse digitally-driven movements may indeed benefit from a degree of hierarchy and leadership (‘Old’ models) as a means to control the crowd and achieve direction and cohesion.

Step 2: But don’t prioritise Old Power over everything else

Yet, as recent movements suggest, orienting attention purely towards Old Power actors and objectives and foregoing the power of the crowd also leaves activism vulnerable to inward collapse. For example, the current Insulate Britain movement seeks to highlight political inertia on GHG emissions and fuel poverty. It does so through orienting its actions almost entirely towards government actors (the stalwarts of Old Power), and failing to build public consensus beforehand. Arguably, this approach is embedded in a prioritisation of Old Power - ignoring the crowd in favour of the hallowed halls of politics.

By targeting their disruptive tactics toward ordinary people rather than fossil fuel companies responsible, the movement has succeeded only in alienating a general public that could have been a key source of support. Indeed, their ‘tactical stupidity’ has now generated an online storm that threatens to undermine the movement. This remains a cautionary tale as to the risk of being outflanked by New Power, if movements neglect to ‘go bilingual.’

Step 3: Bring them together

In order to leverage the New/Old Power framework to cultivate the power to ‘make change happen’ (Question 2), we therefore have to ‘go bilingual’: translating the potential of New Power into tangible legislative and/or political change by selectively embracing the best of Old.

Conclusions

When we started this blog series, we wanted to interrogate whether Timms and Heimans’ New/Old Power framework could help us better understand a new landscape of digitally-mediated activism, and use that understanding to better ‘make change happen’. Applying the framework for the first time to a context of activism, we have been able to move beyond stale debates over individual instances where digital tools have ‘succeeded’ or ‘failed’, to consider instead the nuance in between.

Importantly, the key lessons learned support a broader concern with activism’s impact measurement. As our former lecturer Duncan Green wrote recently, this sort of ‘influencing MEL’ (monitoring, evaluation and learning) is both important and immensely challenging: “it’s a lot harder to measure the impact of a behind-closed-doors bit of advocacy, than more traditional aid activities like vaccines or handing out seeds and tools.”

Our conclusions support this by pointing to the importance of intangible impacts - by definition, hard to measure. Yet if epistemic victories matter, both as an end in themselves and as a means to a more tangible end, our blog must advance a call to change the way we measure activism. There remains a risk otherwise that the current MEL structure will hinder change, nurturing an activism oriented towards ‘quick wins’ over more meaningful long-term objectives like shifting norms and values.

Where we end, therefore, is with two calls to action:

First, the New/Old Power framework is clearly valuable in helping us understand contemporary activism, particularly that which mobilises digital tools. But ideally, we have to go further than understanding: using the framework to cultivate activism’s power to create positive change. To do so, budding activists must learn to ‘go bilingual’: drawing on the strengths and weaknesses of Old and New Power’s values and models.

Second, cultivating New/Old Power will also rely on toppling an MEL system that prioritises tangible ‘wins’ over intangible shifts in power dynamics. A legacy of Westernised development policy, changing this structure must be a central concern if we are serious about creating and catalysing an activism of the marginalised: accountable to those activism serves, not those who fund it. Indeed, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Having finished her academic pursuits for now (Geography BA from Cambridge; Development Studies MSc with Distinction from the LSE), Nina is now working as a junior public sector consultant at PricewaterhouseCoopers. So far, she has worked on issues of local government reform but hopes to expand this to gain experience working with central government and international actors in the coming months. To get in touch, contact her via LinkedIn or follow on Twitter (@NewhouseNina).

Charlie Batchelor is a Freelance Research and Policy Consultant. He received his Masters in International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies with Distinction from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). For business enquiries: cjd.batchelor@gmail.com. He can also be followed on Twitter: @charliejbatch

Photo by SevenStorm JUHASZIMRUS from Pexels