Never Heard of ‘Human Rights Economics’? You have now

Just been skimming an interesting new paper by Caroline Dommen, with an ambitious purpose – to brand and describe a new branch of economics – Human Rights Economics (HRE).

Her starting point: ‘in many ways economic thought and practice currently disregard human rights. HRE is of the view that the world needs an economic system that is fairer for people and the planet, that promotes social and economic justice, that integrates a plurality of views and traditions and that is consistent with human rights in both its processes and outcomes.’

She argues that ‘human rights can help us challenge some of the assumptions that cause economics to be out of step with some of today’s key challenges, such as overconsumption of natural resources or growing inequalities.’

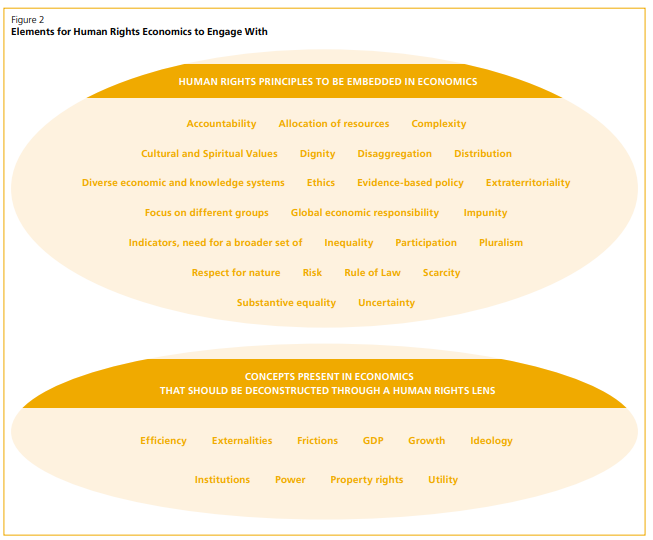

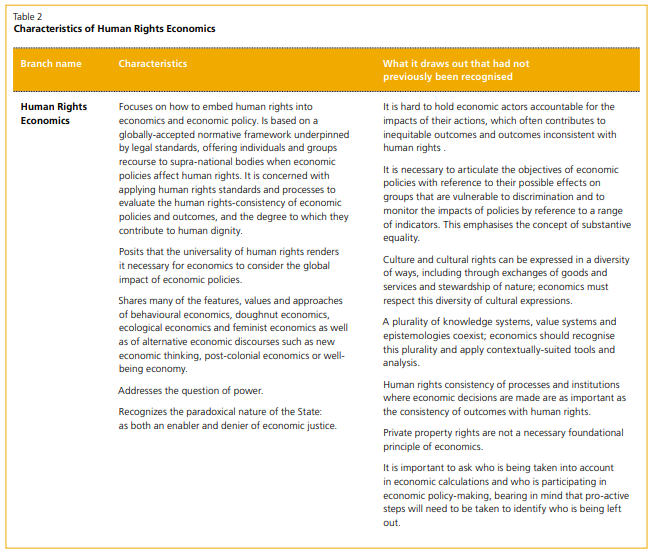

Her ‘enquiry’ ‘starts by analysing the factors that characterise different branches of economics – such as behavioural, feminist or stratification economics, noting what factors each of these has brought to light and contributed to economic thinking and practice.

It draws on these as a basis for identifying what factors a new – Human Rights Economics – branch would bring to light. It also draws on a strong body of existing work on economics and on human rights to examine ways that human rights and economics have been treated together, in order to identify obstacles to fertile interactions between the two fields.’

Conclusion? ‘Human Rights Economics shares many of the perspectives of other branches of economics such as doughnut economics, ecological economics, feminist economics or stratification economics. It also shares many of the perspectives and objectives of alternative approaches and discourses such as heterodox economics, Buen Vivir or Wellbeing economy.

Beyond this, in a number of respects Human Rights Economics can help push the boundaries of mainstream economics, for instance by bringing the human rights legal framework and implementation mechanisms to bear, or by drawing attention to the blind spots of other branches of economics.

For example human rights draws attention to the fact that private property ownership is not the only means of holding, using or managing resources. Recasting property rights could have a transformational impact on economics.’

And an inevitable, but interesting, NMR (needs more research) section:

‘areas in which further research is needed to enhance the impact of human rights on economics in the future. One avenue would be to survey successes and failures in the human rights community’s engagements with economics.

A specific recommendation is to work within academia to ensure that human rights students have some grounding in economics, and vice versa. Joining forces across disciplines will be essential.

Perhaps the most important strand of work going forwards is to demonstrate the relevance and applicability of human rights in economics. Positive examples of how human rights can inform and influence economic policy include initiatives such as UK studies on distributional impacts of tax and welfare reforms on groups of people who are vulnerable to discrimination, human rights-based economic justice advocacy in South Africa and human rights audits of economic policy in the USA and Mexico.’

Overall, this is ambitious stuff, proposing a whole new sub-discipline within (or overlapping with) economics as a whole. A bit like Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, but with more lawyers. Think it will catch on?]

This first appeared on From Poverty to Power.

Photo by beytlik