India’s Vaccine Diplomacy

Against the trend of vaccine nationalism, India is emerging as one of the major global suppliers of COVID-19 vaccines, writes Dr Biswajit Dhar, professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

For over two decades, India has acquired the reputation of being the “pharmacy of the world” as its strong generic pharmaceutical industry has been supplying affordable medicines conforming to quality standards to the global markets [1]. This reputation grew out of the critical interventions that the Indian companies had made during the HIV/AIDS pandemic, by supplying affordable antiretroviral medicines to African countries, when the major pharmaceutical producers had demanded excessively high prices for these medicines [2]. Subsequently, after the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria became a reality as a multi-stakeholder initiative to reduce the burden of these diseases, the India’s generic industry emerged as one of the largest suppliers. Also significant is that fact that exports of medicines from India, which were around a billion dollars at the turn of the century, are currently well over $20 billion.

In keeping with its historical role as a provider of affordable medicines, India has taken two significant initiatives to overcome the scourge of the COVID-pandemic. The first is to make vaccines widely available, which is in response to the growing evidence of the criticality of making COVID-19 vaccines accessible to all. The second initiative is a joint proposal tabled along with South Africa in the World Trade Organization (WTO), which seeks temporary waiver from the implementation and enforcement of four forms of intellectual property rights (IPRs). The objective is to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines, medicines and other medical products are freed from the encumbrances of these IPRs, thus making them affordable. The twin initiatives underline a key message for the global community: in pandemic times, medical products must be treated as global public goods.

Over the past month, India has now emerged as one of the major suppliers of COVID-19 vaccines. The country is able to play this role given its partnership with the Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer by number of doses (the company claims it can produce 1.5 billion doses annually). In June 2020, SII entered into a licensing agreement with AstraZeneca [3], a British-Swedish pharmaceutical company, to supply one billion doses of the Oxford University COVID vaccine to middle and low income countries, including India. SII is currently supplying its vaccine, “Covishield”, to the Government of India. Prior to this tie-up, another India biopharmaceutical company, Bharat Biotech International Ltd together with the Indian Council of Medical Research, the government agency promoting biomedical research, began their collaboration developing a COVID vaccine, “Covaxin”.

Even as it was organizing its COVID-vaccine roll-out, the Indian government announced an elaborate “vaccine diplomacy” strategy for providing vaccines to most of its neighbors, and a sizeable number of other developing countries, including those from Africa. India’s seven neighbors in South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Other countries that have already received “vaccine assistance” are Seychelles, Myanmar and Mauritius. In the South Asian region in which China’s growing presence has been clearly discernible over the past few years, the Government of India’s “vaccine diplomacy” could help in making the playing field more even.

India has decided to supply 10 million doses of the vaccine to Africa and 1 million to UN health workers India under the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI). Among the individual countries, Bangladesh is the largest beneficiary having received 7 million doses of “Covishield” vaccine, of which 2 million doses are in the form of grant, while Nepal has received 1 million. Bhutan and Maldives have received 150,000 doses and 100,000 doses respectively, while Sri Lanka and Afghanistan have both received 500,000 doses. Other than its South Asian neighbors, Government of India has supplied 1.5 million doses of “Covaxin” vaccine to Myanmar. Mauritius and Seychelles have been sent 100,000 doses and 50,000 doses of “Covishield,” respectively. Several other countries, including Bahrain, Barbados, Dominica, Oman, are also part of India’s “vaccine assistance” program. Thus, India is using its soft power to assist developing countries, a role that it has increasingly been playing as a development partner.

Vaccine supplies to the aforementioned countries should be seen as a part of the development partnership initiative that the Government of India has been pursuing since the early 1950s. This initiative was formalized in 2012 with the establishment of the “Development Partnership Administration”, which, while extending support to other developing countries, recognizes that the “most fundamental principle in cooperation is respecting development partners and be guided by their development priorities”[4]. Essentially, India’s development partnership is geared towards meeting the identified needs of the partner countries as is technically and financially feasible [5]. In other words, India has been pursuing a “demand driven” development cooperation program and is, therefore, better suited to meet the requirements of the recipients.

Another important aspect of India as a supplier of COVID-19 vaccines is that the government allowed vaccine exports on commercial terms, mostly to upper middle income countries seeking them, even when an embargo was imposed on commercial sales of vaccines in India. Morocco, Brazil and South Africa are among the countries that would benefit from this policy stance. Morocco is the largest importer of vaccines from India (6 million doses), while Brazil and South Africa have imported 2 million doses import 1 million doses of “Covishield” respectively. Details are provided in the Annex table.

The real value of India’s “vaccine diplomacy” was seen when Canadian Prime Minister, Trudeau, sought Prime Minister Modi’s assistance for vaccine supplies from SII. Over the past few months, relations between the two countries had soured, and therefore India’s “vaccine diplomacy” helped bring normalcy. Although Canada had firmed up deals with seven vaccine suppliers, timely supplies have severely impacted its vaccine roll-out plans. Supplies from SII will help Canada make up for the shortfall in its vaccine supplies.

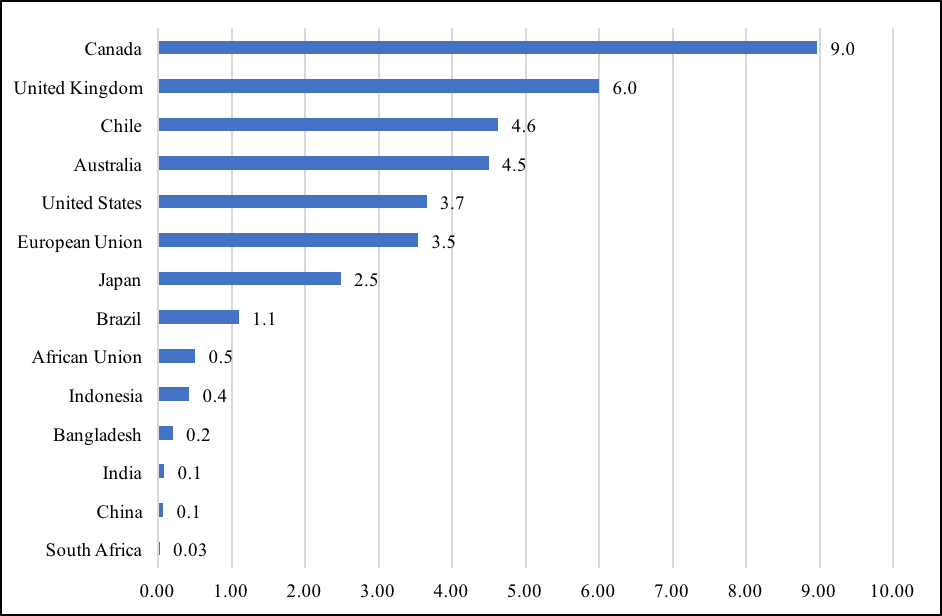

The Indian government’s vaccine sharing policy with partner countries is without doubt a standout in times of the alarming precedent of “vaccine nationalism” practiced by several countries, instead of recognizing vaccines as global public good. According to Duke University’s Global Health Institute, a group of advanced countries, accounting for only 16 percent of the world’s population, have secured for themselves 60 percent of the global vaccine supplies. Canada heads the list of “vaccine nationalists,” having assured vaccine supplies that is nine times its population, while the United Kingdom has stocked enough doses to vaccinate every citizen six times. Other countries to secure vaccine supplies that are well beyond their domestic requirements are Australia, Chile, the United States, and members of the European Union. On the other hand, India is sharing its available vaccine supplies with several countries, and also ensuring that the domestic demand is met.

Not surprisingly, global supplies have been seriously affected at a juncture when every country is trying to overcome the pandemic-induced crisis. Several studies have cautioned that inadequate availability of vaccines, especially for smaller countries, would prolong their recovery thus triggering significant increases in global inequalities. A Rand Corporation study has concluded that if low and low-middle income countries (LLMICs) are not able to adequately immunize their populations, high income countries (HICs) would be severely impacted. According to the study, total cumulative economic cost for 30 HICs could increase from $82 billion in 2020–2021 to $258 billion in 2023–2024. The United States could incur the highest relative cost, $15.7 billion in 2020–2021, rising to $49.3 billion in 2023–2024, while the corresponding figures for Germany were estimated to be $9.9 billion and $31.1 billion respectively.

A recent study commissioned by the International Chamber of Commerce has observed that that equitable distribution of vaccines is in the economic interest of every country, especially those that mostly depend on trade. The study elaborates a significant point that the President of the European Commission Dr. Ursula von der Leyen had made during the height of the pandemic last year, “None of us will be safe until everyone is safe”. The study concludes that assuming that all HICs fully vaccinate their populations by the middle of 2021 and poorer countries find themselves largely excluded, the global economy could lose upward of $9 trillion, which is larger than the combined GDP of Japan and Germany. But if 50 percent of the developing country citizens get vaccinated by the end of 2021, the study concludes that the global economy would lose up to $4.4 trillion. Clearly, the costs of non-cooperation in responding to the vaccine requirements of developing countries could be substantial [6].

Thus, central to the possibility of an early recovery of the global economy from the COVID-19 induced crisis is affordable access to vaccines and medicines, especially for the citizens of the developing countries. Towards this end, India and South Africa had taken an important initiative in October 2020 in the WTO through their proposal to ensure accessibility and affordability of COVID-19 vaccines, medicines, and related products [7]. The proposal, which has now been co-sponsored by 55 other members of the Organization and has also been supported by Holy See [8], argues in favor of granting temporary waiver from the WTO members’ commitments to implement or apply four forms of intellectual property rights [9] so that these critical products and their technologies are widely available for “containment or treatment of COVID-19” [10]. At the height of the last major pandemic, namely, HIV/AIDS, WTO members had adopted the Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which introduced flexibilities in the implementation of the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), recognizing that the “TRIPS Agreement does not and should not prevent Members from taking measures to protect public health”. They also affirmed that the TRIPS Agreement “can and should be interpreted and implemented in a manner supportive of WTO Members’ right to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all” [11]. This spirit needs to be rekindled for overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article was originally published in Pandemic Discourses.

Dr Biswajit Dhar is Professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He has served as the Director General of Research and Information System for Developing Countries, a think-tank of India’s Foreign Ministry, and had also helped in establishing the Centre for WTO Studies of the Government of India, of which he was the Head for several years. Dr. Dhar has been a member of the Indian delegation in several multilateral treaty negotiations, including the World Trade Organization, and has participated in expert groups of several inter-governmental organizations.

Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich from Pexels

Figure 1: Availability of Vaccines Per Capita (as on 8 February 2021)

Sources:

- Total confirmed doses of vaccines procured by countries from Launch and Scale Speedometer, Duke Global Health Innovation Center

- Population of individual countries for 2020 from Worldometer

- EU population in 2020

Annex Table: India’s COVID-19 Vaccine Supplies

| Country | Quantity Supplied (in ‘000 doses) | ||

| Grant | Commercial | Total Supplies | |

| Bangladesh | 2000 | 7000 | 9000 |

| Morocco | 0 | 7000 | 7000 |

| Brazil | 0 | 4000 | 4000 |

| Myanmar | 1700 | 2000 | 3700 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0 | 3000 | 3000 |

| Nepal | 1000 | 1000 | 2000 |

| Sri Lanka | 500 | 500 | 1000 |

| South Africa | 0 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Mexico | 0 | 870 | 870 |

| Ghana (COVAX) | 0 | 600 | 600 |

| Argentina | 0 | 580 | 580 |

| Afghanistan | 500 | 0 | 500 |

| Ukraine | 0 | 500 | 500 |

| Maldives | 200 | 0 | 200 |

| Mauritius | 100 | 100 | 200 |

| Kuwait | 0 | 200 | 200 |

| UAE | 0 | 200 | 200 |

| Bhutan | 150 | 0 | 150 |

| Serbia | 0 | 150 | 150 |

| Mongolia | 150 | 0 | 150 |

| Bahrain | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Oman | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Barbados | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| UN Health workers | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Dominica | 70 | 0 | 70 |

| Seychelles | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| Egypt | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Algeria | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Dominican Republic | 30 | 20 | 50 |

| El Salvador | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| Total | 6750 | 28940 | 35690 |

Source: Ministry of External Affairs: Vaccine Supply

[1] Dhar, Biswajit and Reji K. Joseph. 2019. The Challenges, Opportunities and Performance of the Indian Pharmaceutical Industry Post-TRIPS. In Liu, Kung-Chung, Uday Racherla (eds.) Innovation, Economic Development, and Intellectual Property in India and China. ARCIALA Series on Intellectual Assets and Law in Asia. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8102-7_13.

[2] Dhar, Biswajit and KM Gopakumar. 2020. Towards more affordable medicine: A proposal to waive certain obligations from the Agreement on TRIPS. Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper No. 200. Bangkok: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

[3] AstraZeneca entered into a licensing agreement with SII to supply one billion doses for low-and-middle-income countries, with a commitment to provide 400 million before the end of 2020 (https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/articles/2020/astrazeneca-takes-next-steps-towards-broad-and-equitable-access-to-oxford-universitys-potential-covid-19-vaccine.html).

[4] https://mea.gov.in/Overview-of-India-Development-Partnership.htm

[5] Standing Committee on External Affairs (2011-2012): Fifteenth Lok Sabha. Ministry of External Affairs – Seventeenth Report. Lok Sabha Secretariat. New Delhi.

[6] Çakmaklı, Cem et. al. 2021. The Economic Case for Global Vaccinations: An Epidemiological Model with International Production Networks. ICC Research Foundation. <https://iccwbo.org/publication/the-economic-case-for-global-vaccinations/>

[7] WTO. 2020. Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment And Treatment of Covid-19: Communication from India and South Africa.

[8] https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2021-02/holy-see-trips-wto-intellectual-property-rights-coronavirus.html.

[9] The scope of waiver includes the following: copyright and related rights, industrial designs, patents, and trade secrets.

[10] For a detailed discussion on the India-South Africa proposal, see, Dhar, Biswajit and KM Gopakumar. 2020. Towards more affordable medicine: A proposal to waive certain obligations from the Agreement on TRIPS. Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper No. 200. Bangkok: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

[11] WTO. 2001. Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health: Adopted on 14 November 2001.