What Mobilises the Ukrainian Resistance?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has met with fierce resistance from the Ukrainian military and from ordinary citizens. Drawing on survey evidence, Pippa Norris and Kseniya Kizilova explain who among the Ukrainian population is willing to fight, and what motivates their decision to take up arms.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the tragic events in Ukraine concerns the sudden uprising of thousands or even millions of ordinary citizens, who have abandoned their normal humdrum lives and loved ones to take up arms and defend the mother country with AK-47 assault rifles, homemade incendiary Molotov cocktails, and even by kneeling to block Russian tanks. Some are likely to be seasoned army veterans with combat experience, including fighting Russian forces in the 2014 annexation of Crimea and invasion of the Donbas region. But others are reported to have never held a gun in their life. Ukraine’s Defence Minister urged anyone who can hold a weapon to join the country’s Territorial Defence Forces.

This massive civilian uprising seems unprecedented in the speed of rapid mobilisation after Putin’s fateful decision to invade. Reports suggest that after just a few days, the armed resistance, by the Ukrainian professional military and volunteer civilians, had initially strengthened national morale, slowed the expected pace of the Russian invasion, and inflicted some serious damage. Yet rifles are no match for rockets. Nor are citizen soldiers a practical defence against cluster bombs. Massive convoys of Russian tanks continued to rumble towards major cities and to encircle Kyiv. But, among ordinary citizens, who is willing to fight for Ukraine? Why would Ukrainians, or indeed any people, voluntarily face ‘pain, dirt, blood, and death’, in the words of President Zelensky?

What fuels resistance by ‘citizen-soldiers’?

Several explanations are commonly offered for the mobilisation of the Ukrainian resistance including the role of democratic freedoms, Ukrainian nationalism, and/or ethno-linguistic regional cleavages.

Many popular accounts claim that millions of Ukrainians are volunteering to defend the liberal ideals of democracy and freedom, the principles and values at the heart of the European Union. In this view, Ukrainians are at the frontline of the West standing for democracy against belligerent threats from Russia’s authoritarianism. Putin’s televised address on 24 February sought not just to reassert control over a neighbouring nation-state in the Soviet Union’s former sphere of influence, but also to divide NATO, to restore Russia’s place in the world, and to end the rule-based liberal world order respecting principles of national self-determination.

At the same time, however, claims that the Ukrainian resistance is firmly committed to liberal democratic ideals may be more rhetorical than real. President Zelensky can use this appeal to attract Western kit and support, such as in his address to the Munich Security Conference: “Putin began a war against Ukraine, and against the entire democratic world”. In practice, Ukrainian democracy has had a chequered and volatile history, with the Varieties of Democracy regime classification shifting regularly between electoral democracy and electoral autocracy over successive decades. Today there remain endemic problems of corruption, attacks on media freedom, and political instability. As a result of these experiences, Ukrainians may well have become increasingly disillusioned with lofty claims of liberal democratic ideals and principles.

By contrast, the explanation for why Ukrainians are willing to fight may be simpler and more prosaic if closely related to the powerful forces of national and ethnic identities. In this interpretation, volunteers are likely to be more strongly motivated by Ukrainian nationalism, pride, and patriotism, the emotional tug of the yellow and blue, and deep anger towards Russians invading the Ukrainian homeland.

In a related claim, willingness to fight may be attributed to the long-standing ethno-linguistic cleavage which divides Russophone and Ukrainian regions and populations. This is often over-simplified into depicting Huntington’s ‘clash of civilisations’ splitting provinces, oblasts and municipalities in the East and West along the dividing line of the Dnipro river. Western provinces are regarded as more pro-Ukrainian, European-leaning, agrarian and Catholic, while by contrast Eastern provinces are seen as more Russophone, industrialised, Orthodox and pro-Russian. In practice, however, revised scholarship suggests that a more complex regional pattern exists, with diversity and overlap among cross-cutting cleavages, and socially-constructed ethnic divisions sharpened by Russian aggression.

Survey data

Some systematic evidence to explore the underlying reasons associated with Ukrainian willingness to fight, and the importance of nationalism, ethnic cleavages, and the protection of democratic freedoms, is available from pooled European Values Study/ World Values Survey (EVS/WVS) data. The most recent 7th wave included interviewing a representative sample of 2,901 Ukrainians in autumn 2020, well before the recent drums of war although during the long simmering conflict which has existed since the annexation of Crimea.

Interviews were conducted throughout Ukraine (except for the annexed Crimea and occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts). In total 10,926 Ukrainians have been surveyed at roughly five-year intervals on successive occasions by the EVS/WVS ever since the mid-1990s to monitor cultural change. The results can be compared with the equivalent surveys of 16,172 Russians surveyed over successive surveys since 1989. One of the standard questions in the survey, asked ever since the first wave in the early-1980s, concerns willingness to fight for one’s country:

“Of course, we all hope that there will not be another war, but if it were to come to that, would you be willing to fight for your country?”

This invites a simple binary yes-no response (excluding the ‘don’t know’ category, with only valid answers included in the analysis here). This standard item has been analysed in several previous academic studies, such as here, here, and here. The willingness of citizens to fight for their country is widely regarded as important for each country’s capacity to defend itself, to draft citizens voluntarily, and to mobilise the civilian population in times of war.

Public opinion monitored in the series of EVS/WVS surveys can give insights into the underlying reasons for ordinary citizens being willing to fight. But one important data limitation should be emphasised: the autumn 2020 Ukrainian survey provides only a snapshot of public opinion well before the latest outbreak of war. In a November 2021 IRI survey, for example, when asked about the three most important issues facing Ukraine, only 8% mentioned relations with Russia. Clearly the intense shock of the current Russian invasion may well prove critical in changing attitudes and behaviour, spurring many Ukrainians into action who might never have contemplated bearing arms before. More recent surveys among Ukrainians by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) indicate that resistance to the potential threat of Russian armed intervention rose over the last few months.

In a survey by Rating on 1 March 2022, 80% of the Ukrainian respondents said they were ready to defend the territorial integrity of Ukraine with weapons in hand. Compared to the pre-war times, this figure has significantly increased (it was 59% in 2020). The highest level of readiness is observed in the West and in the Centre of the country, while a slightly lower level of readiness is observed in the South and in the East. But even in the South-Eastern regions, readiness to fight for the country is extremely high (almost 80% in the South and almost 60% in the East).

The existing EVS/WVS surveys can therefore provide reliable data to help us understand the general profile, values, and attitudes of those most willing to fight prior to the most recent invasion. Estimates of the actual strength of the resistance can only be monitored in subsequent studies after the extraordinary conflict ends.

Trends and patterns

Trends below in Figure 1 show that willingness to fight has usually been higher in Russia than Ukraine. Overall, in the 2020 EVS/WVS survey, around three-quarters of Russians said that they would be willing to fight compared with about 70% of Ukrainians. But the proportion of Ukrainians willing to defend their country rose sharply by 13 percentage points in recent waves – even before the intense anger and outrage over the Russian invasion and destruction of their home.

Figure 1: Trends in willingness to fight in Russia and Ukraine

Note: Responses to question Q151: “Of course, we all hope that there will not be another war, but if it were to come to that, would you be willing to fight for your country?” % Yes. Source: EVS/WVS

National identities (land)

What explains ordinary people’s willingness to fight? ‘National identities’ (land) provide one potential answer, a concept that refers to what Benedict Anderson called ‘imagined communities’ or a socially constructed sense of belonging which often reflects shared historical traditions, languages, religions, cultural values, and territorial boundaries. Feelings of national identity can exist for diasporas without states, exemplified by the Kurds in the Middle East, and the borders of states like Canada and the United Kingdom may contain multiple national identities.

The concept of national identities can be monitored in the 2020 Ukrainian survey by three EVS/WVS questions tapping into first, a sense of national pride; second, feeling close to your country; and third, whether respondents are Russophone speakers at home. Willingness to fight should be predicted by stronger Ukrainian nationalism and weakened by Russophone ethnic identities, both individually and by region.

Support for democracy (freedom)

By contrast, another potential explanation relates to the desire to defend democratic principles and protect fundamental liberal rights and freedoms. Support for democracy can be monitored by three standard measures in the pooled EVS/WVS 2020 survey, namely: approval of democracy as a very good way of governing the country; disapproval of having a strong leader in power who doesn’t have to bother with parliament or elections; and confidence in the core agencies of the regime, including government, parties, the civil service, and parliament. Strong democrats should be more willing to fight than those sympathetic towards authoritarian values and principles.

Controls

In general, sex and age need to be controlled in any analysis, at a minimum, since these are some of the most predictable demographic characteristics linked to willingness to fight. A familiar attitudinal gender gap linked to the deployment of military force and use of war has been consistently observed in many societies, including the United States. Also, while the young commonly sign up for action, older cohorts are normally more physically limited in their capacity to engage in strenuous and demanding military action, hence they are exempt from conscripted service.

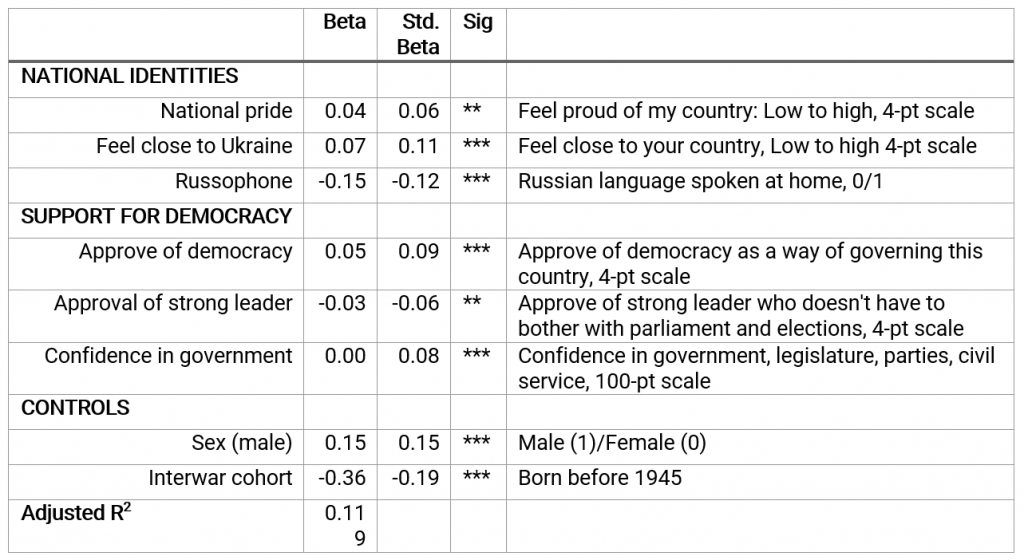

Table 1: Who is willing to fight for Ukraine?

Note: The dependent variable is willingness to fight for Ukraine (No 0 / Yes 1). Sig P **=.010 *** = .001 Source: World Values Survey / European Values Study, Ukrainian survey only (2020) 1,721 respondents.

The results in Table 1 confirm that, as expected, all the selected indicators significantly correlated with willingness to fight. Feelings of Ukrainian pride and self-identified closeness to the country were indeed positive predictors of willingness for military service, while Russophone populations were more reluctant to join up. Similarly, however, approval of democracy and confidence in the key agencies of the Ukrainian state were also linked to mobilisation, while approval of strongman rule predicted greater reluctance to engage. The forces of nationalism are strong but appeals to democratic freedoms also appear to contribute towards the mobilisation of citizen soldiers.

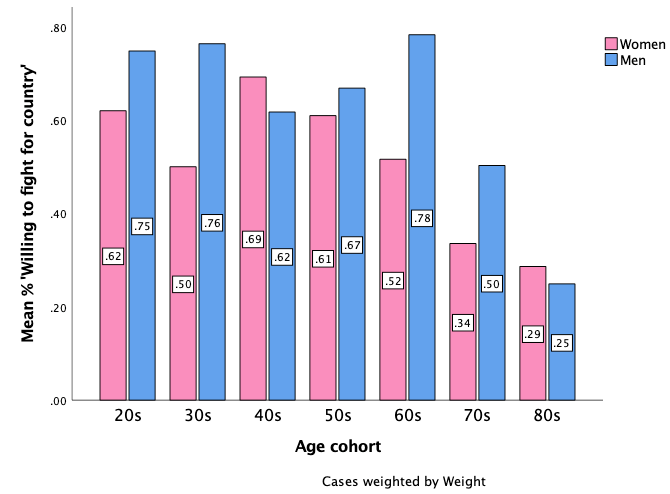

Finally, as expected, there was a substantial gender gap and the interwar cohort, in particular, were less willing to fight. Figure 2 illustrates these patterns. The gender gap is observed across nearly all cohorts, especially for those in their 30s, when women may have the primary responsibility for care of children and elderly dependents living at home. The biggest drop by cohort comes for those in their 70s and 80s, the least physically capable of military duties. Many other attitudes and background factors like education, income and religion were also examined, but none of these significantly strengthened the explanation.

Figure 2: Willingness to fight by age and sex

Source: World Values Survey/ European Values Study, Ukrainian survey only (2020) 2,901 respondents.

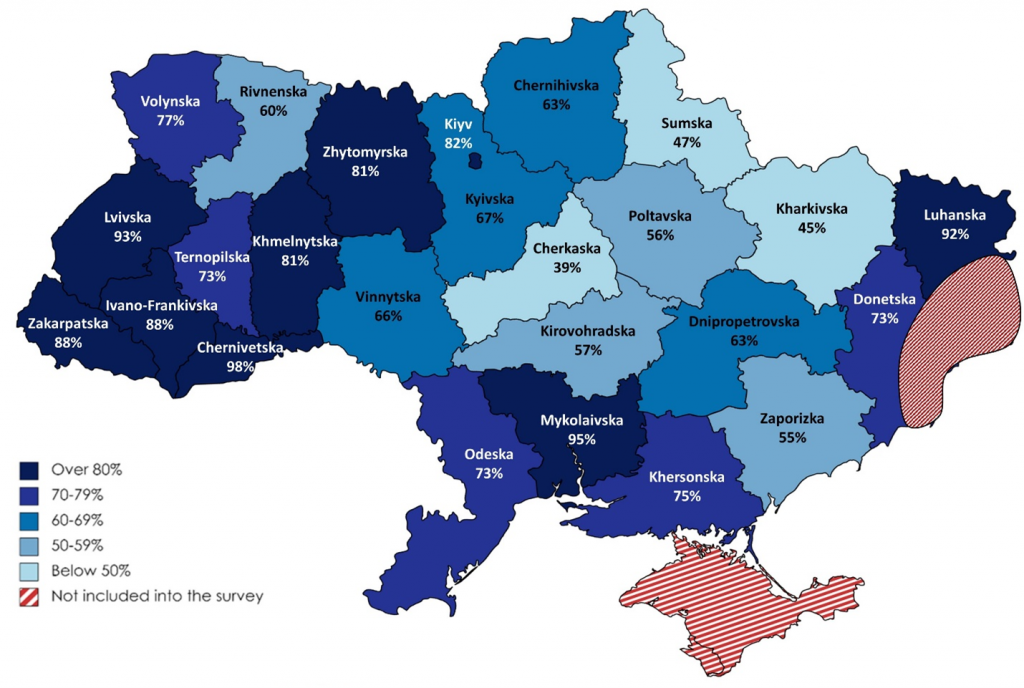

Finally, what of ethno-linguistic cleavages and how does the pattern vary geographically across the whole country? The survey data shows that differences are complex but they do reflect the classic ‘East’ versus ‘West’ division. Western regions display more pro-Ukrainian and patriotic attitudes, for example from 2011-2020, willingness to fight surged by around 26 points in the Western provinces, and by 16 points in the East and Centre, but by only 5 points in the South (in part, due to technical differences excluding Crimea in the 2020 survey).

At the same time the geographic differences among provinces should not be attributed only to ethno-linguistic cleavages; among Russian-speaking Ukrainians, 51% were willing to fight, compared to 61% among the Ukrainian-speaking population. Far from reflecting fixed ethno-linguistic identities, however, there has been a rise of nationalism and willingness to fight for their country in the East and in the South – particularly those regions bordering the annexed Crimea and the occupied Donbas territories. With the Russian army stationed just a few kilometres away, the existential threat is much more real in the Ukraine-controlled parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and Kherson, Odessa, and Mykolaiv located next to Crimea, rather than in other regions.

Figure 3: Willingness to fight by province

Source: EVS-WVS dataset for Ukraine (autumn 2020), N=2,418.

Conclusions

Overall, therefore, willingness to engage in defending the country prior to the outbreak of war is predicted by strong feelings of Ukrainian nationalism, as many expect. But it is also associated with the endorsement of democratic values among ordinary citizens, controlling for the demographic characteristics of sex and age. This is not just rhetoric; feelings of nationalism (our land), as well as the genuine desire to protect democratic freedoms (our rights), fuel activism in the resistance. In Zelensky’s words to the European Parliament: “Our people are very much motivated, very much so, we are fighting for our rights, for our freedoms, for our life.”

The Ukrainian army, of course, but also ordinary people, have shown a tremendous example of community solidarity by offering help to each other with transportation, food, security, and much, much more, as well as millions actively fighting in a courageous resistance against the massive might of the Russian military. Events and public opinion continue to unfold. Any predictions are foolhardy. Our feelings are in turmoil, divided between hope and fear.

But some say that the revolution of 2014 gave birth to civil society in Ukraine. Perhaps the best outcome, probably reflecting a triumph of our hearts over heads, is that this bloody and shocking war may ultimately give birth to a stronger Ukrainian nation and global rejection of the forces of authoritarian repression. But the final outcomes – for Ukraine, European security, and indeed the rules-based liberal world order – are currently lost in the fog of war.

Pippa Norris is a comparative political scientist and prolific author who has taught at Harvard University for more than three decades. @PippaN15 Kseniya Kizlova (PhD in Sociology) is Head of the World Values Survey Association Secretariat and Associated Research Fellow at V.N.Karazin Kharkiv National University in Ukraine. @KsenniyaKK

This first appeared on the LSE's EUROPP blog.

Photo by Mathias P.R. Reding from Pexels