China, Australia and the Fourth Wall

Brian Stoddart explores Australia's pantomime politics and its actors' performances in response to China's increasing regional power.

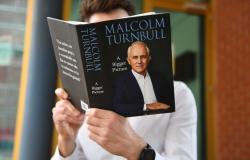

Reading ex-Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s recently released (and flawed) autobiography while watching his successor’s “let’s go with Donald Trump’s call for an inquiry into the Chinese virus” trick, I was much reminded of the theatrical/dramatic art concept of the Fourth Wall.

Essentially, that convention posits an invisible wall between performers and audience where the latter can see in but the performers do not look out. That is to say, performers are intent on creating an imagined world while the audience, observing but not participating, watches them creating that world.

It follows, then, that “Breaking the Fourth Wall” is where actors knowingly speak directly to the audience. Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s television series, Fleabag, which sees her speaking directly to the camera and, therefore, the audience is a notable recent example. She discusses this at length on a recent Scriptnotes podcast with the actor Ryan Reynolds and screenwriters John August (Charlie’s Angels) and Craig Mazin (Chernobyl).

In Turnbull’s case, the Fourth Wall principle applies in three interlinking ways that resonate throughout the politics and global affairs space.

First, he is intent and intense on the Canberra “world” that he creates and has created around him – here, perhaps, read “the swamp” to which Donald Trump returned repeatedly during 2016 speeches, “Number 10” in London, Beijing, Phenom Penh and all the rest.

Throughout his story, Turnbull talks more about the internal machinations of his party than about what the people who elected him might actually have wanted. That extends to policy. In all the agonising pages devoted to “his” creation of some major policy or another, he effectively assumes what the electorate/audience might want.

That is to say, he maintains the Fourth Wall.

Second, though, he occasionally glances through the wall in search of audience sympathy. Either outflanked or ignored in all those magnificent policy initiatives, he seeks audience approval where he cannot get it internally, on the stage as it were.

Then, third, as the machinations against him ramp up, he places himself outside the wall and in among the audience, inviting those now around him to deplore the unreasonable actions taken by others on the stage in having him dismissed.

This latter point is telling. Turnbull was never the most comfortable politician, the self-made squillionaire who came in to help the country but did so almost exclusively and solely on his own terms.

Throughout the book, for example, he notes repeatedly that he “trusted” people like now-Prime Minister Scott Morrison even though the man was a proven serial leaker to the press, and like Matthias Cormann who “ran the numbers” against Turnbull at the end.

Turnbull invites us to see this as “broken trust” when, in reality, it was his inability and/or failure to manage those internal pressures that brought it on and allowed it to flourish. He was not managing on the stage.

But as Morrison and his colleagues now show, Turnbull is not alone in varying the use of the Fourth Wall in order to suit the purpose, and nowhere is that more pronounced than in the current Australian government’s approach to China in the wake of COVID-19.

Indeed, by raising the question about who constitutes the actual audience Morrison is extending the principle. The Fourth Wall is fundamentally a two dimensional phenomenon, players and audience, but the present Morrison approach to China has some of the audience being on stage.

Morrison termed the outbreak a “pandemic’ in advance of the World Health Organisation, so now argues his government was well ahead of the game. That in itself is questionable, but now the initial outbreak appears to be under control he has gone on the attack and joined Trump’s call for an international inquiry into the “Chinese virus”. Moreover, Morrison’s newly-minted and politically-appointed envoy in Washington, former Senator Arthur Sinodinos has joined in volubly.

This is where the question of audience arises.

COVID-19 has decimated the Australian economy. That is not unique to Australia, but there are some distinctions. Tourism and export education are among Australia’s top four export earners, and both have been smashed by the virus with the China slant massively significant.

Take export education. Last year it was worth approximately $A38 billion with Chinese students a major contributor. Over the years, some Australian universities have relied heavily on this and effectively built it into their forward budgets to subsidise research (at least partly in pursuit of higher world rankings) and capital investment. Several institutions have more than thirty percent of their budgets reliant on this income.

When the virus forced closure of the borders, those fee-paying students did not arrive and that in turn created a pipeline effect because they would then not be present in subsequent years. Almost immediately, leading institutions were declaring prospective losses of up to and exceeding $500 million with a cumulative total nearing $2 billion and more.

This was and remains a catastrophe, leaving aside questions about risk management practices in universities and the approach taken to those practices by the national regulator.

And the government’s response was just as catastrophic.

First, the responsible Minister assured the higher education sector it would receive all the monies allocated for domestic student support as planned, irrespective of enrolments. That is, there was no additional money to cover the international student situation.

Second, the Government then went to great pains to ensure universities would not be eligible for emergency funding that would ensure continued employment for staff.

Third, and perhaps worst, the Government advised all stranded international students that they would receive no support and were best advised to return home, this time leaving aside questions of how that might occur given the closed borders. The universities individually then had to come up with their own rescue packages, aggravating the original problem.

Why on earth would any government massacre a major export industry in this way? Because Morrison was on the stage looking at his fellow actors rather than considering the education export audience.

It starts with the Liberal-Country Party coalition’s increasing suspicion of what it considers to be bastions of the “left” and those include, perhaps even start with the university sector (despite the fact that at least half the enrolments in Australian universities are now in business faculties that are scarcely on the left).

Turnbull was a victim of this pronounced lurch to the Right in recent years, and that gang has been instrumental in seizing any additional opportunity to bash China. Andrew Hastie, from Western Australia, is among its leaders, a far right figure who served in Afghanistan and was a member of Australia’s SAS (the Special Forces unit). He is now an avowed China basher who is as much a problem for his own party as for others, and that aligns with his pro-American stance on just about everything. In turn, that conforms with the American administration’s push on the World Health Organisation and every other avenue that might deflect attention from the management crisis wrought domestically to produce a greater American casualty rate than that suffered during the Vietnam War.

In all of that, Hastie is joined by a strong media push from the Murdoch press, primarily, that has also recruited several think-tankers from organisations like the Australian Strategic Policy Institute that declares itself to be independent but is funded significantly by the Department of Defence and is run by an ex-Defence hawk.

Given that situation, which is merely the Australian version of a global push, it is fair to suggest that much of the angst about China is prompted by concerns over its growth in the two great basins of the Pacific and the Indian oceans. (See Bertil Lintner’s recent book on the Indian Ocean, and Robert Kaplan’s on the South China Sea). And this is where the focused gaze on fellow-actors on stage starts to cause Morrison problems.

Western Australia, for example, is massively reliant on China. In this case, iron ore replaces students but the effect is the same, so some of Morrison’s actors become less keen on antagonising China. Principal among those is Matthias Cormann, the federal Finance Minister who orchestrated Turnbull’s exit but comes from the West so must downplay Hastie in recognition of the power and bank balances of the iron ore bosses, Andrew Forrest and Gina Rinehart. Forrest, in particular, has pushed this, arranging large amounts of Personal Protective Equipment to be brought in from China for front line health service workers. And in response to a most outspoken criticism of Australia by the Chinese Ambassador, Forrest had China’s Consul-General in Melbourne effectively gate crash a press conference run by the federal Health Minister.

The Ambassador had made it quite clear China had and would not hesitate to use the power to turn off the investment taps in agriculture, tourism and education (you can bet the Australian universities groaned at that) – he did not mention iron ore.

In the initial stages of all this Western Australia’s Labor Premier, Mark McGowan, got along with his federal colleagues by agreeing to fight the virus and focus their joint fury on a set of cruise ships that landed several patients ashore around Australia, notably Sydney and Fremantle in Perth, several of whom sadly succumbed to the illness. McGowan ranted at “virus ships” rather than at a ‘virus country” and Morrison could keep him on stage.

That disappeared as Morrison’s main audience gaze turned towards Donald Trump and the strong conservatives in his own rank. Unsurprisingly, McGowan backed Andrew Forrest and the national coalition against COVID-19 splintered again.

So, in Western Australia, some of Morrison’s fellow actors have, like Turnbull, deserted to the audience which means the former will need far greater management skills than the latter if he is to get a rousing curtain call.

And the same will apply to many of his global counterparts with their own stages and Fourth Walls.

They might all reflect on the point that pantomime is a profligate breaker of the Fourth Wall, as in Peter Pan: “if you believe in fairies, clap your hands” to save Tinker Bell.

But they would also do well to remember that most of the audience can discern where the stage starts and ends.

Brian Stoddart is a former Vice-Chancellor at La Trobe University in Australia, a long-time observer of Asian and global affairs, and now a prize-listed crime novelist and award-winning screen writer.