India is Not Your Default Democracy

Lalit Chennamaneni examines the decline of Indian democracy and the Global North’s contention with it. A comment on Amrita Narlikar’s ‘Why should Germany work more with India?’.

In a recently published article ‘Why should Germany work more with India?’, Prof. Amrita Narlikar of the GIGA institute in Hamburg argues for a significant boost of Indo-German relations. At the heart of Prof. Narlikar’s argument lies the assumption that India, for all its messiness and flaws, is an established democracy, firmly committed to pluralism and the rule of law. As such, it is a formidable partner to counter Chinese assertiveness and the spread of populism.

Indian democracy is not alive and well but progressively decaying. This is my fundamental disagreement with Prof. Narlikar. The issue is not if India is a rising global power that Berlin, Brussels and Washington will have to engage with but rather what kind of power is rising; what kind of relationship will emerge from this.

Since coming to power in 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have passed discriminatory policies, like the notorious Citizenship Amendment Act and cracked down on dissent in the media, civil society and academia. Stoked by the BJP’s Hindutva ideology, caste- and religious hate crimes and violence against minorities have increased. Parliament has been disempowered on multiple occasions and the Supreme Court has turned out an unruly ally to the Prime Minister. In all of this, big capital has been staunchly loyal and the Ambanis and Adanis of India have extraordinarily benefited from the government’s neo-liberal policies. In turn, the BJP’s coffers are flooded with unaccountable money. It is not coincidence that under Modi, India ‘quantum leaped’ on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, while Amnesty International was forced to suspend its operations.

Prof. Narlikar does not mention any of this. Instead, she vaguely suggests that whatever is happening in India is a ‘home-grown interpretation’ of democracy that should not automatically be condemned just because it does not fit with the Global North’s script of liberalism. ‘Democratic governance is a zone of contestation, which grows and diminishes at different points’, she writes and, in this sense, India has its rightful place under the ‘broad umbrella’ of liberalism and democracy.

To think of lurking autocracy as a particular interpretation of democracy is not just cynical, it is to tiptoe around the demagogue in the room. At some point the kind of democratic back and forth Prof. Narlikar assumes becomes a one-way street into the abys, and the Indian government has clearly taken this route. It is not interested in the peaceful contestation of its ideas in a public forum but eagerly undermining the very prerequisites of meaningful debate, pluralism and the rule of law. Press freedom for instance is rapidly dwindling as the government is systematically killing democracy ‘with a thousand cuts‘. India has become a posterchild for the kind of democratic backsliding it is supposed to be a bulwark against.

What has India’s domestic politics got to do with its relationship to Germany and the Global North?

For one, understanding India as an increasingly illiberal state challenges the narrative of a self-evident bloc of democracies. Instead of a fellowship of shared values bound to confront autocratic assertiveness, India’s relationship to the Global North is one of necessity, not of morals.

On a more fundamental level however, the situation in India draws attention to the general state of democracies. According to Prof. Narlikar, Germany, the EU and the US are all ‘imperfect’, suggesting that this would somehow relativize India’s decline. But two wrongs do not make a right. In fact, the hypocrisy of liberal democracies, from human rights violations, systemic racism and rampant neoliberal exploitation is well documented and these issues do shape North-South relations.

When in the early 2000s, Germany still believed to democratize China through ‘Wandel durch Handel’, CDU politicians campaigned for ‘Kinder statt Inder’ (Children instead of Indians) and against the migration of more Indian IT-specialists to Germany. The racist slogan was later picked up by a Neo-Nazi party. India and Germany, a ‘match made in heaven’?

Nested within the ‘imperfections’ of the democratic bloc is the question of how these countries should make for a particularly good defense of the free and open world order, and what ‘free and open’ means beyond supply chain security and trade agreements. What is completely absent in the new cold-war scenario between democracy vs. autocracy is a genuine reckoning with the question of how democratic democracies really are.

Indeed, while German and Indian politicians celebrate each other for 70 years of diplomatic relations, they speak very little of the issues that are ostensibly the cornerstone of their engagement. Chancellor Merkel has remained timid on the abysmal situation in Kashmir, while Germany’s Ambassador thought nothing of visiting the Nazi-inspired RSS. In a recent response to a parliamentary query, the German government demonstrated how remarkably oblivious it is to the situation in India. On the European level, the EU parliament postponed a vote on a resolution in January 2020 that condemned the situation in Kashmir and the Citizenship Amendment Act in fear of jeopardizing the EU-India summit a couple of weeks later. To be fair, the German government quietly approached the Indian embassy after the closure of Amnesty International and the EU parliament did voice some concerns but this is far from a clear and principled position.

Democracy cannot be taken for granted like this and all the shiny international summits, dialogues and forums where India is a well-received guest cannot hide the fact that the country is not the default democracy in Asia everybody wants it to be. Neither can it hide the fact that countries of the Global North, in a mixture to ignorance and political expedience, have been content with it. In this sense, Indo-German relations deserve all the attention that Prof. Narlikar demands, although for very different reasons. Repeating the ever-same mantra of shared values, freedom and rule-based order without substance however won’t suffice.

Lalit Chennamaneni is a graduate from Humboldt-University zu Berlin. He is currently on a Humboldt research track scholarship to prepare for a PhD.

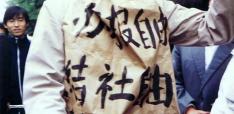

Photo by Prabhala Raghuvir from Pexels