Decolonise your Mind and Practice

This is the third chapter in a forthcoming e-book, entitled 'Decolonial Education and Youth Aspirations'. Syra Shakir argues that to decolonise your pedagogy, curriculum and support to students, you must first decolonise your mind; Decolonised psychology, changing hearts and minds.

Higher Education (HE) in the United Kingdom has seen a long-standing problem of differential outcomes between White and Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students (Arday, Branchu & Boliver, 2022). BAME students are disadvantaged in their experiences in HE; they are less likely to leave higher education with a first class or 2:1 degree and less likely to be employed six months after graduating compared to their White peers (Advance HE 2018b; UUK/NUS, 2019).

A particular area of concern is around engendering a sense of community and belonging, especially for those students who already experience marginalisation (Cureton & Gravestock, 2019; Thomas, 2012). Research highlights the university experiences of students from minority backgrounds are shaped by feelings that they do not belong, a teaching curriculum that omits a diverse range of perspectives, an academic environment which favours the white majority, staffing and student bodies which are not reflective of marginalised communities, and a system which is set up to accommodate the needs of white students rather than students of colour (Bunce et al., 2010; Bernard et al., 2014). It is these experiences collectively which can lead to feelings of ostracization from the wider university community and little sense of belonging for students of ethnic minority backgrounds which can then lead to drop out (Thomas, 2012; EHRC, 2019).

There have been several student-led campaigns across HE which have sought to address the dominance of the western canon of thought and knowledge production (Arday & Mirza, 2018) and the ways by which university curriculum has been racialised as white (Peters, in Arday & Mirza, 2018). It appears that our current higher education system omits significant aspects of our shared connected history (Connell, 1997; Bhambra, 2014, 2016) and this is symptomatic of entrenched institutional racism which still permeates higher education and society at large (Dei et al., 2004; Shilliam, 2015). University pedagogy and curricula, dominated by White European canons, contributes to the overall experience for Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students in relation to engagement, belonging and marginalisation (Ahmed, 2012; Nwadeyi, 2016). Recent research indicates that BAME students are rarely provided with opportunities to negotiate, challenge, co-create, nor decolonise these white canons of knowledge permeating higher education (Bhopal, 2014; Andrews, 2019; Rollock, 2016; Arday, 2019). Moreover, BAME students are engaging with a curriculum that does not reflect their heritage, history, lived experiences nor their future pathways.

A lack of belonging and feeling disconnected to the curriculum are not only experienced by students of BAME backgrounds but by students of many backgrounds (Meehan & Howells, 2018; Thomas, 2017). Furthermore, differential outcomes and racialised experiences negatively impact not only those who are the target but also the wider community overall (Cohen, 2021). According to the prominent critical race theory (CRT) scholar Derrick Bell (2018), helping those most disadvantaged in our community will benefit everyone. The Office for Students (OfS), the main body that regulates higher education in the UK, requires universities to address both belonging and the curriculum to better support student experiences and outcomes to fulfil their conditions of registration as a university (OfS, 2023).

To investigate these issues, I embarked on using co-creation as a pedagogic approach to explore racialised experiences raised by students within the Race Equality Charter (REC) survey in 2019, situated in a post 1992 university in the North of England. Co-creation involves students and staff working together to design curricula and involves meaningful supportive relationships through adopting relational pedagogy (Bovill, 2020). Co-creation is becoming more widespread and positive outcomes relating to raised student achievement and better engagement, such as attendance, contribution, have been demonstrated (Bovill, 2019; Cook-Sather et al., 2014; Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017; Shakir & Siddiquee cited in Jamil, 2024). However, these tend to be ‘one off’ interventions. The methodological approach used a critical race theory (CRT) lens to frame the extended life cycle of interventions. This is because a key tenet of CRT, ‘a contradictory closing case’ outlines that ‘one off’ interventions do not make real, sustainable changes and thus a quick return to the discriminatory status quo occurs (Delagado & Stefanic, 2017). The further tenet of CRT that the approach adopted was listening and learning from people of colour. This involved creating safe spaces for students (both those of BAME and white backgrounds) to share their lived experiences to inform changes to policy and practice at the university moving forward.

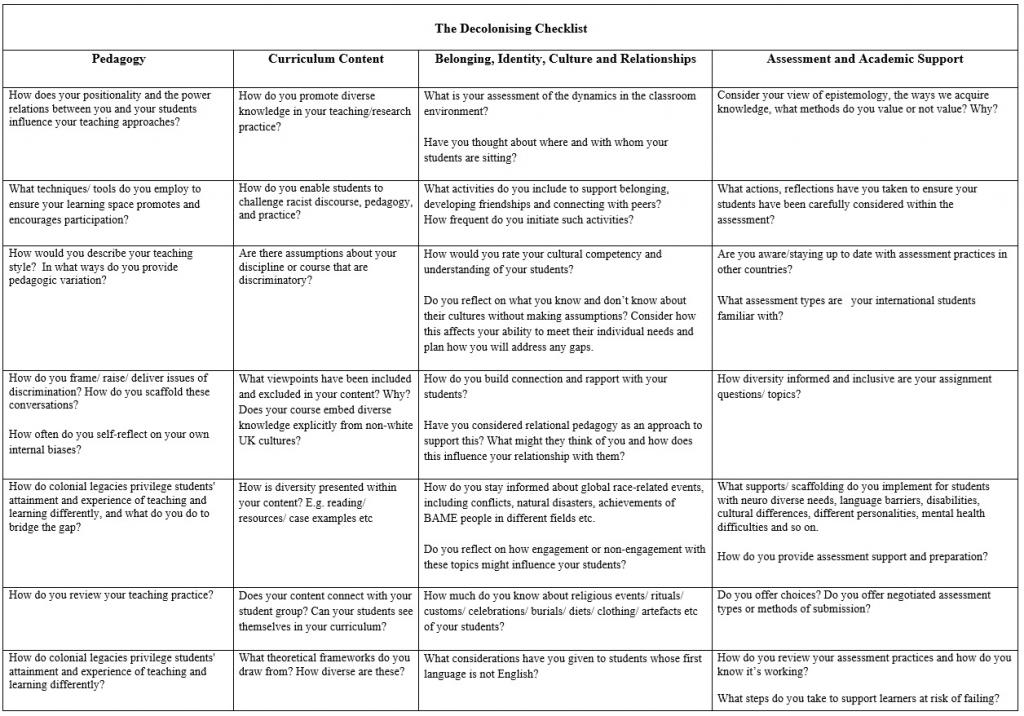

My overall research over the last four years aimed to investigate whether student belonging, and attainment are connected and therefore addressing both through co-creation rooted in a decolonised curriculum and pedagogy underpinned in anti-racist practice can support closing gaps for students. This chapter explores one part of the overall research: the decolonised framework developed through student staff co-creation over four years and provides a way forward for educators and student services wanting to decolonise their teaching, learning, assessment, classroom practices and support to students. Students who participated were from multi-disciplinary backgrounds across all levels of study, undergraduate through to postgraduate and from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. They shared their lived experiences and journeys navigating university and made several recommendations to the institution to improve student outcomes. It is their voices and wisdom that inform the decolonising checklist. I will now go on to define decolonising, co-creation and anti-racism in my context.

Decolonising in higher education

Decolonising in my context, refers to the process of challenging and rethinking the existing education systems that are rooted in colonial legacies and practices; the higher education (HE) environment is an example of this (Arday & Mirza 2018; Sian, 2019). Decolonising involves critically examining and altering the curriculum, teaching methodologies, assessment, academic support, and structural racism within the educational system to address and rectify the biases, inequalities, and Eurocentric perspectives that dominate education. This process aims to incorporate indigenous knowledge systems and voices that have been historically marginalised or erased, fostering an inclusive, equitable, and diverse educational environment.

Co-Creation

Co-creation has been fundamental to my work in decolonising the curriculum and my pedagogic approach (Bovill, 2020). In co-creation there is a move away from the typical form of teaching structures adopted in HE, whereby the educator is the source of all knowledge and ‘fills up the empty vessel student’. There is a shift in power dynamics (Shakir & Siddiquee, 2023; De Los Reyes, 2002) which means the ‘educator becomes the educated’ and a reciprocal teaching relationship takes place for learning to happen (Werder, et al., 2010). The students are empowered to be ambassadors of their own wisdom and to share this not only with staff but with their peers through peer teaching and mentoring in a classroom of all possibilities (hooks, 1994). The focus of the co-creation interventions were around equity, identity and lived experiences, which spoke to students directly and was about something that mattered to them to bring about positive changes to their educational journeys (Shakir & Siddiquee, 2023; Freire & Ramos, 1996; hooks, 1994). The founding parents of teaching and researching philosophies central to the approaches I have adopted are rooted in papa Freire’s pedagogy of the oppressed (Freire, 1970) resonating very personally to students as it concerned issues that directly affected them and to which they could be part of the solution. At the same time, the co-creation approach offered teaching with love, at the core of mama hooks’ practice (hooks, 1994). It provided compassion, care and nurture to students who had been disadvantaged, experienced significant challenges, and were provided with a safe space to share such experiences.

Anti-Racist Practice

- Accept racism exists

- Not being racist is not enough

- Time to listen and learn from people's experiences

- Information, understand the terms, data, research

- Racism harms everyone, know the reality

- Accountability and responsibility

- Care, compassion and empathy

- I can make a change

- Support, report, challenge

- Time to take action and make changes

(Shakir, 2024, p.14.).

This acrostic defines anti-racism and calls for action to become anti-racist. Anti-racism asserts that all racial and ethnic groups should be treated equally and have equal opportunities (Kendi, 2019). However, it requires more than belief, it demands active efforts to dismantle systems, privileges, and behaviours that sustain white supremacy (Delgado & Stefancic, 2023). In higher education, anti-racist practices create a more inclusive environment by addressing systemic racism (Salisbury & Connelly, 2021), fostering belonging for marginalised students (Hampton, 2020), and enhancing academic success (Thomas, 2012). These practices help reduce racial disparities by providing tailored support, such as mentoring and academic resources (Jankowski, 2022). Integrating anti-racist education into curricula cultivates critical thinking and a reflective learning environment (Tate & Bagguley, 2017), equipping students with essential skills for a just society (Jayakumar, 2008). Universities play a crucial role in this transformation. I will now present the decolonizing framework.

Decolonise your mind

So how to decolonise? The easy trap staff often fall into is to simply diversify although this is only one ingredient of the decolonised approach. Decolonising our education means that we have to first understand the profound impact colonisation has had on our education and our society. Examining our approach to practice and teaching pedagogy requires a critical reflection on how we learn, what we learn, and whose knowledge is valued within our curriculum. It is essential to interrogate the perspectives that are included in our educational frameworks and, just as importantly, those that are excluded. Marginalised voices, particularly those from the Global South, have often been erased or deliberately omitted, contributing to a persistent imbalance in knowledge production.

The dominance of Eurocentric, Western narratives, often shaped by white, male perspectives, reinforces existing power structures, privileging certain epistemologies while devaluing others. Understanding how knowledge is acquired and recognising the methods we prioritise or dismiss, is central to challenging these inequities. Pedagogy plays a crucial role in either reinforcing or dismantling these racialised power dynamics, making it imperative for educators to embed cultural knowledge, foster a deep understanding of diversity, and develop strategies that address the individual needs of students. By actively seeking out and amplifying marginalised perspectives, we can create a more inclusive and equitable learning environment that values the contributions of all global knowledge systems.

Higher education institutions continue to operate within a Eurocentric curriculum that thrives in an elitist, neoliberal-saturated environment. This reality prompts critical internal questioning about the extent to which our educational structures reinforce existing inequalities and fail to accommodate diverse perspectives. The ongoing legacy of colonialism persists, shaping lived experiences and influencing differential outcomes that disadvantage individuals from historically marginalised backgrounds. Recognising these systemic barriers is essential to fostering a more inclusive and equitable academic space.

Educators must actively engage with the concepts of structural whiteness, privilege, and positionality, acknowledging their roles within these systems. Through meaningful allyship, colleagues of colour can be empowered, ensuring their voices are heard and valued. This requires a commitment to seeking out and critically engaging with data that highlights disparities not only within higher education but across wider society. Understanding these patterns is crucial for developing interventions that address the persistent inequalities experienced by individuals from BAME backgrounds in contrast to their White counterparts.

A key component of this work involves listening to and responding to the lived experiences and voices of people of colour. Their insights should serve as a foundation for shaping targeted interventions that tackle the complex and deeply rooted issue of racism within learning, teaching, and assessment practices. Beyond the classroom, these approaches should extend to broader institutional policies and frameworks to ensure meaningful, long-term change.

Advancing one’s practice in this area necessitates engagement with applied educational theoretical frameworks such as Critical Race Theory (CRT), the works of Paulo Freire, Frantz Fanon, and bell hooks, among others. These perspectives offer valuable tools for understanding how racism is perpetuated within educational spaces and provide guidance on teaching with real love, fostering empowerment, and supporting the most disadvantaged students.

Finally, ongoing self-reflection is crucial in this journey toward anti-racism. Educators must regularly assess their progress, critically examining their actions and their impact. By adopting a framework of internal reflection and evidencing concrete steps taken toward anti-racist practice, individuals and institutions can ensure accountability and drive meaningful transformation within higher education.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this chapter explores disparities in higher education outcomes for BAME students, systemic biases in pedagogical frameworks, and the need for a decolonised curriculum that reflects diverse knowledge. Research shows BAME students face barriers exacerbated by an exclusionary curriculum lacking inclusivity and belonging. This work highlights the role of co-creation and anti-racist practices in redefining educational spaces to ensure inclusivity and support for marginalised students.

The decolonised framework, developed through student-staff co-creation, challenges the status quo and offers a transformative approach aligned with social justice. By engaging directly with affected students, this framework drives meaningful change in higher education, providing educators with tools to create environments where all students thrive.

Looking ahead, universities must commit to continuous reflection, learning, and adaptation of curricula and teaching practices. The decolonising checklist serves as a guide for educators to scrutinise and improve pedagogy, ensuring inclusivity. By embracing this shift, higher education can better prepare students for a globalised world, leading to more equitable outcomes. This chapter presents a compelling case for systemic change to dismantle barriers and expand our understanding of valuable knowledge.

Syra Shakir is an Associate Professor learning and teaching, strategic university lead on race equity, Office for Institutional Equity at Leeds Trinity University. s.shakir@leedstrinity.ac.uk

Acknowledgements - To all my students who have shared their lived experiences which underpin the Decolonizing Checklist, and to Dr Sean Walton for editing the Checklist.

Resources

To support the framework you may wish to hear expert tips and lived experience from students, please visit: Co-creation project on addressing the awarding gap through anti racist practice.

Further resources and reading is available on Padlet at: The Awarding Gap and Anti Racist Practice, decolonizing, deconstructing, disrupting and developing a socially just consciousness; lets address and action the gaps