Britain’s Relationship with Immigration has Broader Lessons for the International Community

Immigration has formed a key part of political discourse in recent years. With this in mind, it is relevant to examine the extent of division elicited by the issue. Both voting preferences and demographic traits are thought to influence stance, but do certain characteristics have more of a bearing than others? Using the UK as a case study, the analysis of attitudes towards immigration sheds light on some the factors responsible for engendering division on a global level.

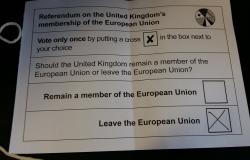

Brexit has revealed new political fault lines in Britain. Whereas party affiliation was once the overarching means of identifying an individual’s political identity, Leave and Remain have now emerged as strong determiners of one’s viewpoint on a number of issues. Immigration is an issue that encapsulates this idea. Its centrality to the Brexit debate cannot be overstated; the Leave campaign revolved around the need to regain control over our borders. This, it was claimed, would enable us to limit the number of migrants entering the country, as we would no longer be bound by the EU’s principle of free movement.

Such assertions were intended to capitalise on the public’s desire for immigration to be reduced- a study from IpsosMORI shows that, in the months preceding the vote, 62% of the population favoured a reduction. Not only this, but such words were designed to nurture the viewpoint that immigration is to blame for many of the nation’s socioeconomic ills. The Leave campaign overtly stated that controlling immigration would reduce the ‘big strain’ on public services, and enable us to prevent ‘dangerous criminals’ entering from Europe.

This language sheds light on the extent to which Brexit was framed as a way of avoiding the supposed harmful effects of immigration. The motive behind such emphatic, emotive wording is clear; galvanise the public, stoke the fires of anti-immigrant sentiment and deliver a Leave vote in the process. It was a course of action that yielded success. Closer analysis of the key factors that influenced voting behaviour points to the considerable weight held by immigration. In the aforementioned study, IpsosMORI asked participants about the issues most important in deciding their vote. The results were conclusive- 68% of Leave voters stated ‘the number of immigrants coming to Britain’. In contrast, only 14% of Remainers proffered the same answer, evidencing the effectiveness of the Leave campaign’s divisive narrative. Taking this into account, the EU referendum has added a further layer of complexity to an issue already steeped in contrasting opinions. Whilst party affiliation can provide insight into one’s stance, Leave and Remain have arguably emerged as even stronger indicators.

Scaremongering surrounding immigration in the lead up to the referendum continued a much-longer trend of migrant demonisation in Britain. As the analysis above reveals, this had very real manifestations in the ballot box. The UK has lessons for the international community here. Within the context of the top 10 international migrant destination countries, only the Russian Federation had a greater percentage of its population in favour a reduction of immigration. The prevalence of anti-immigrant rhetoric has a profound impact on attitudes towards the issue.

Given the monumental role that immigration played in the entire Brexit process- with the desire for tighter controls such a dominant theme- one would be forgiven for thinking that attitudes reached a nadir around this time. It is all the more pertinent, therefore, that public opinion regarding its impact has actually softened in recent years. Over the course of IpsosMORI’s study, which began in February 2015 and concluded in October 2016, the proportion of respondents rating immigration’s impact as positive increased. This process was particularly marked in the immediate aftermath of the referendum, plausibly precipitated by its outcome reassuring voters that immigration will be reduced. Conversely, the hostile rhetoric surrounding the vote may have triggered a swell of public opinion in support of migrants. Yet what emerges above all else, is the intrinsic link between one’s vote in the referendum and attitude towards migrants.

In relation to how attitudes change over time, it is important to discuss generational differences of opinion on immigration. Whereas Brexit has added a new dimension of division, age is a demographic characteristic long thought to correlate with stance. Younger generations tend to look upon immigration more favourably; in a survey conducted in September 2017, 59% of 18-24-year olds stated that immigration is beneficial to society. Where does this positivity stem from? Common Vision point out that millennials have grown up in an interconnected world, and are frequently exposed to the ‘rapid exchange of information across borders.’ Regular contact with those from different backgrounds breeds tolerance and respect, which in turn fosters openness towards immigration. In contrast, no more than 29% of those aged 55+ held the same viewpoint.

This corroborates the findings of similar research undertaken on a global level. According to the International Organisation on Migration (IOM), 23% of young people globally favour increased levels of immigration, in comparison with only 17% of those aged 55 and over. Such findings point to the significance of growing up in an increasingly diverse world where the principles of openness and inclusivity reign supreme. According to Gallup research, younger people tend to be more positive than their elders about various aspects of life. The IOM found that this ‘youth effect’ was found in most migrant-hosting nations, with the notable exception being the Russian Federation, where there were no marked generational differences in attitudes towards migrants.

In light of this, it is unsurprising that 73% of those aged 18-24 voted to Remain, and 60% of those over 65 voted to Leave. Such statistics point to the strong relationship between age, voting behaviour and attitudes towards immigration. Geography is a further demographic characteristic believed to play a role here. Scotland and England exhibit very different voting patterns, with Scotland consistently demonstrating support for progressive, left-of-centre policies. As a result, Scotland is associated with more positive views about immigration. Interestingly, research from NatCen suggests that this is not the case, with Scots holding hugely similar views to those south of the border. 46% of Scots view immigration as economically beneficial, a viewpoint held by 47% of those in England. Correspondingly, the proportions in both countries viewing immigration as culturally beneficial was identical.

The Migration Observatory point out that Scotland does show greater levels of positivity towards certain types of migrants, such as highly-skilled workers. This may be borne out of Scotland’s dwindling working-age population, and the fact that immigration is a way of remedying this. At present, the £30,000 salary threshold and need for a sponsor licence make such workers difficult to attract. Scotland’s relationship with immigration can be seen as a microcosmic reflection of a wider international trend. On a global level, countries often form their immigration policies in response to labour market needs and ‘in accordance with their demographic objectives’. This then influences public opinion; Scotland is an example of where government immigration policies become aligned with public attitudes towards the issue. Curiously however, Scotland’s unique relationship with immigration is something of an anomaly in a European context, a continent where public opinion is notably negative towards all forms of immigration.

NatCen’s research suggests that age is a stronger determiner of immigration stance than nationhood. On both sides of the border, the proportion of those aged 18-34 holding a positive view of immigration’s impact was almost identical. Curiously, a greater proportion Remain voters in England expressed positive views about immigration than those in Scotland. The reasons for this are unclear, but potentially linked to the absence of senior politicians in Scotland campaigning for Leave. Additionally, educational background was also found to be a more significant factor than geography, with degree holders more likely to express positive views towards immigration. Interestingly, this trend is not reflected globally, where the picture is far more complex. In Africa, higher levels of education are synonymous with negativity towards immigration, whereas in Latin America, education levels are not a clear predictor of opinions in this regard.

Voting behaviour and demographic characteristics are both thought to have a bearing on attitudes towards immigration. Brexit has evidenced the former, eliciting fresh division over the subject. Regarding the latter, analysis reveals that age plays a more pivotal role than geographical location. The salience of age is reflected on an international level, with those growing up in our increasingly globalised world holding more positive views. Yet educational background is far more complex globally, with huge disparities existing between different regions.

Cameron Boyle is a political correspondent for the Immigration Advice Service, an organisation of immigration solicitors that provide legal aid to asylum seekers.

Image: (Mick Baker)rooster via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)