Enron, Madoff, and U Visas

Karl Muth explores the world of ‘U visas’ and argues they could have a wider application than many think.

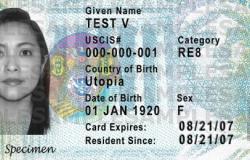

There is a special visa that most people have never heard of. Most Americans have heard of H visas (for skilled workers) or T visas (for victims of human trafficking) as these visas end up in the news. But U visas, jokingly called “undercover visas” by street gangs, allow victims of serious crimes to “earn” the right to stay in the U.S. by providing valuable testimony and assistance to law enforcement. My view is that U visas are an important tool for law enforcement, but that their focus should be shifted away from violent crime and toward white collar crime. This blog explains why.

Most of the people receiving U visas today are victims of violent crimes, sex crimes, and robbery. While these crimes are no doubt hurtful and serious, they are not the criminal activities where immigration officials should go to extraordinary lengths to reward cooperating witnesses. Instead, we should focus on encouraging people to come forward with information around criminal securities violations, fraud perpetrated against shareholders, intentionally misleading filings for privately-held corporations, money laundering, Ponzi schemes, and similar activities.

Do I think crimes against shareholders are more serious than crimes like rape and attempted murder? Not in the case-by-case heinousness test, but in the broader sense – then yes. I do think these crimes are a “bigger deal” in terms of maintaining trust in the American system of markets, progress, and prosperity. And I believe violations of laws intended to protect the functioning of markets, the governance of companies, and the public trust in companies limited by equity must be policed and prosecuted at a nonpareil level of priority.

By shifting the focus to higher-value crimes that impact thousands of shareholders rather than one or two victims, we reward immigrants whose professional lives are of the highest value and whose investigative acumen (in areas like accounting and analytical finance) is lacking in law enforcement. We also create a heavily-incentivized class of financially-savvy whistleblowers on Wall Street and elsewhere, a small percentage of whom might receive passports eventually (and likely contribute far more to the tax base than the immigrants more likely to witness street crimes or fall victim to a gang-related shooting).

The good news is that Congress seems to, at least in part, agree with me. In 2014, Congress added fraud in foreign labour contracting (a provision popular among a bizarre coalition of anti-immigration Republicans as well as union-backed pro-labour Democrats) to the crimes where U visas could be issued. I propose this provision should be further expanded to include a wider variety of non-violent, financial crimes including embezzlement, extortion, and so forth, with an emphasis on shareholder rights and protecting stakeholders in both public and private corporations.

Would a Russian immigrant investment banker at a Madoff feeder fund have been motivated by a U visa to share his suspicions? Would a British immigrant accounting expert at one of Skilling’s senior desks at Enron been willing to come forward if offered a U visa? I’m not sure. But these people were, in the broad sense, certainly victims of these crimes and should be in a position to be rewarded in new, interesting ways for contributing expertise to the law enforcement effort surrounding them. Let’s revise the U visa and make the “U” stand for “unorthodox whistleblower reward.”