Faith and International Development: Beyond Secular Assumptions

On Friday 8 March, Faith Centre director James Walters delivered a lecture for the LSE International Development department’s Cutting Edge Issues in Development series. Two of the Department’s students, Krista Kartson and Emily Featherstone, share their thoughtson this thought-provoking talk regarding the role of faith in international development.

What feeling do you get when you think about mixing religion and international development? For those who come from a “western” background like me, this can be an uncomfortable thought. It conjures ideas of exploitation, imperialism and paternalism; identities that we’ve been trying to distance ourselves from since the decolonisation wave of the 1950s and 60s.

But James Walters argues that we should not fear this conversation. In fact, acknowledging and confronting our secular biases would make us better development practitioners. Walters proposed three western myths about religion and how we might challenge our assumptions in order to better understand and engage with the global population.

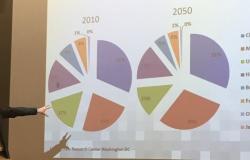

Myth 1: Religion is going away. While secularisation may be on the rise in the West, religion is growing in the rest of the world and it’s not an exclusively demographic phenomenon. Evidence suggests that contrary to conventional wisdom, even countries with advancing economies (e.g., China, India and Turkey) are seeing a resurgence of religion. The positive correlation between secularisation and development may very well be a “European exception”, and not the rule.

Myth 2: Religion is a private matter of personal beliefs. From a western perspective, we tend to assume that our value of separation of religion and state is universal. If religious beliefs are practiced at all, they are commonly reserved for our private lives. This idea is often lost in the developing country context, however. In many developing countries, religious beliefs play a significant role in society: gender and family relations, healthcare and education, financial practices, political discourse, etc. As a development practitioner, it would be negligent to ignore the role of religion in the public sphere.

Myth 3: Secularity is a neutral position. It is detrimentally ironic that in an attempt at inclusivity, development actors will avoid engaging with a society’s “religious imaginations,” or the evolving faith narratives that shape the worldview of a person or group. Non-engagement is not neutral and can be taken as discrimination by a society that is deeply rooted in religious tradition.

Walters’ message resonated with my experiences working in Iraq, a developing country with very public religious imaginations. When I told a colleague that I would see her next week, she’d say, Inshallah. During Ramadan, everything moved a little slower…except the tempers (understandably so!). As a female, I sat in the family section of traditional restaurants because the other section was reserved for men only. These are all small, yet very tangible examples of how religion may influence culture and society. I am confident that remaining sensitive to – and at times embracing for myself – the religious imaginations of my environment made me more strategic in decision-making, more understanding as an outsider and more relatable as a friend.

Perhaps discussing religion in the development context need not be so taboo, after all.

Krista Kartson is an MSc Development Management candidate at the LSE and holds a BA in International Studies from American University in Washington, DC. Krista has eight years of professional experience in international relief & development, and most recently designed programmes for displaced persons and returnees in Iraq. Her research interests include land tenure policy and post-conflict stabilisation in the Middle East.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Are you WEIRD?

This is how Dr James Walters challenged students at his Cutting Edge Issues in Development lecture. WEIRD refers to Jonathan Haidt’s acronym: Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. Such a perspective shapes our perceptions of the role of religion in international development – the topic of James’ lecture.

He argued that many in the West, probably myself included, are firm in their belief that religion as a force in the world is declining as societies become more secularised. We tend to think this is positive, on the simplistic terms that less religion = more development. However, it isn’t necessarily so, and globally, us WEIRDs may actually be in the minority with rather Euro-centric ideas. James noted that whilst religion is on the decrease in Britain – 70% of 17-25 year olds claim to be of no religion, for example – it still plays a central role in many countries and people’s lives. Those that are WEIRD-inclined see religion as a private personal matter – have one or have none but it’s not a public thing, in sharp contrast to elsewhere, where faith is embedded, shared and significant.

James refers to the LSE Faith Centre’s embrace of ‘religious imagination’ in their work. It demonstrates the potential significance of religion to the world views people have. It is not enough for those working in international development to merely acknowledge the faith of others – after all, WEIRDs are likely tolerant. There must be understanding of the ways a particular religion grounds its followers in the world. They must work with the presence of faith, for greater effectiveness of development efforts. This is not only a lesson for development, but humanitarianism too, as faith leaders hold the trust of their communities like no other. James demonstrates this with reference to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa from 2014, when faith leaders were pivotal in taming fears and encouraging the move away from traditional burial practices that heighten transmission risk. I found especially interesting the idea that perhaps the ability to freely embrace faith is a pushback against colonial legacies and that the rise of western secularisation (particularly in development) could be seen as neo-colonial.

The lecture finished with a point that will be one of my key takeaways. Given the salience of religion in societies around the world, choosing to not meet with a faith group on the grounds of maintaining neutrality in development may actually be the opposite. I came away mulling over two aspects of the lecture: the assumption of global secularisation is western-centric and that WEIRDs who downplay the significance of engaging with the role of religion in development may not actually be as open-minded as we pride ourselves to be. As we speed towards the end of our time at LSE and perhaps head into work in the field – development or humanitarian – this lecture provided much food for thought.

Emily Featherstone is pursuing an MSc in International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies. She graduated in Geography from the University of Manchester in 2018, where her thesis focused on the UK’s use of foreign aid. She is interested in how humanitarian organisations operate in crises and the new threats that digital technologies pose to the response.

This post first appeared on the LSE Department of International Development Blog.

Photo credit: Krista Kartson.