Global Trade: New Priorities

Markus H.-P. Müller explores the challenge of reconciling the trilemma of efficiency, equity and the environment as we try to move to more sustainable economic models.

Is the global trading system fixable? As I have previously noted (Müller et al, 2023) this now seems a valid question to ask. Managing increasingly complex patterns of corporate and economic interdependence, against a changing global political landscape, has led to increasing scepticism about whether current structures are still fit for purpose. But possible alternatives (e.g. regional trading blocs and economic decoupling) would have considerable economic costs - the IMF estimates it could cost 0.2% to almost 7% of global output depending on the severity of the decoupling (Aiyra et al, 2023).

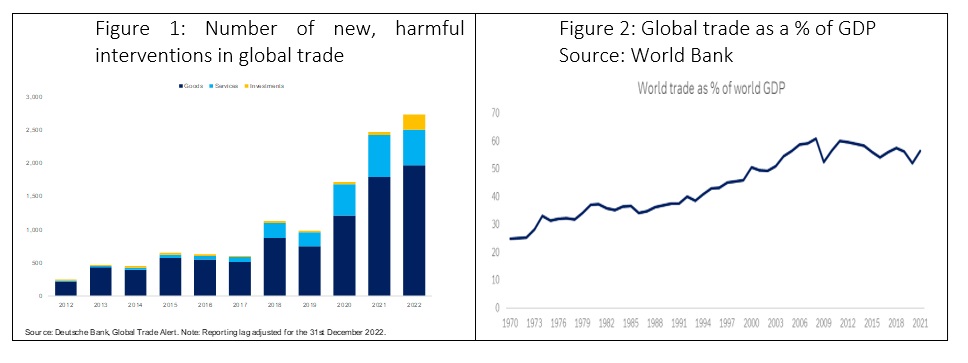

Global trading system stresses have certainly been building for some years. As Figure 1 shows, the number of new harmful interventions in the global trade system has increased sharply in recent years, according to Global Trade Alert data. “Harmful interventions” are defined here as state interventions in trade through methods such as tariffs, import quotas, technical barriers, investment restrictions, requirements for local labour content, export subsidies and so on.

I don’t think this necessarily means the “the end of globalisation”. Trade remains significantly more important than a few decades ago (Figure 2) and, in terms of the goods and services we consume, we still live in a highly globalised world. But perceptions around globalization have changed. As Goldberg and Reed (2023) argue, traditional measures of trade do not capture a shift in policy and public opinion regarding globalisation, for example around a stated desire for national security, an issue we will return to below.

History reminds us that some key globalization themes are long-standing. Technology, for example, has long been a pivotal driver of change, not just in the way goods are produced, also through enabling transport and logistical systems that allow their easier and cheaper distribution. Foreign trade’s vulnerabilities have also been evident for many centuries: international conflict, domestic political resistance, policy changes (e.g. tariffs) and, last but not least, climatic factors and natural catastrophes have long been able to disrupt it. Technology may now, however, be a threat to trade, rather than an enabler, and climatic vulnerabilities are getting more acute.

History also shows us that our understanding of globalisation can lag reality. In fact, the role of economic theory has often been to provide an ex-post rationalisation for globalisation, rather than to drive it. Economists, however great, reflect the times they are writing in – be they Adam Smith (gaining absolute advantage from new forms of production), David Ricardo (comparative advantage in a an increasingly complex international trading environment) or subsequent modifications of this Ricardian model over the last two centuries to suit current concerns (e.g. outsourcing, automation, and vertical and horizontal integration).

Any institutional framework for managing globalization may therefor need to prioritise resilience and adaptability over theoretical perfection. The 1944 Bretton Woods agreement and the institutions it spawned – still the core of our international trade framework – have proved able to do this, adapting to flexible exchange rates (1971-73), the replacement of the GATT with the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994 and the implications of China’s accession to this in 2001. However, is this framework now in danger of being overwhelmed by an ever-growing “spaghetti bowl” of bilateral trade agreements?

Economists do not like bilateral trade agreements because they move us away from a theoretically-optimal trade regime – and open the door wider to further bilateral agreements, future reducing trade efficiency. These are very valid concerns but, as I noted above, any system may need to prioritise durability over optimality.

What worries me more, however, is that the focus of trade disagreements has changed, and in a way that makes finding any form of agreement difficult.

In recent decades, disagreements have often been because the windfalls from trade have been unequally distributed within domestic labour markets. Chetverikov et al (2016), for example, found that increased import competition from China hit low-wage US workers twice as hard as it did the average American worker from 1990 to 2007. Autor et al (2016) argued that workers in industries exposed to foreign competition, particularly from China, experienced greater employment churn and reduced lifetime income.

Now, with rising external trade imbalances and China’s growing technological prowess, the focus of the globalization debate has shifted to national security. There is growing belief that national policy, rather than fostering growth through liberalising trade and financial policies, should instead seek to cut out economic and technological rivals from the global supply chain of critical materials and technologies, through both protectionist policies and regionalisation of supply chains (Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace, 2023a).

Disagreements around perceived threats to national security are difficult to resolve within the existing multilateral trade system. All sides are well aware that the production goods such as semiconductors and electric vehicle (EV) batteries is heavily dependent on free, cross-border trade as a result of highly-specialised supply chains, with some obvious geographic chokepoints – notably Taiwan. The policy approach from China and the U.S. has been to both restrict access of the other country to certain technologies or raw materials, and to try to encourage domestic sources of production. The U.S. has moved to restrict Chinese access to US made technology, software, equipment and talent used to produce advanced computing chips (Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace, 2022), with the extraterritorial nature of U.S. restrictions having major implications for third parties (effectively all foundries use U.S. design, equipment, and tools. At the same time, the US has seen a surge in public sector semiconductor investment under the CHIPs and Science Act (Casanova, 2022). China has reacted with its own spate of domestic spending, bans on the purchase of certain chips, and export restrictions on gallium and germanium, key inputs into advanced semiconductors (Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace, 2023b).

These moves are not primarily driven by economic considerations. Replacing existing international supply chains with local ones would also take years and not be as cost-efficient: under the Semiconductor Industry Association’s hypothetical scenario, if each economy was to have a fully self-sufficient local supply chain, to meet current demand, each economy would have to invest USD1 trillion in incremental upfront investment (Goodrich et al 2021).

Even a brief consideration of the relationship between the U.S. and China shows how destructive a dismantling of economic relations could be. These two countries are highly reliant on each other for trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), and savings. The relationship is not completely lop-sided. Some U.S. jobs may have suffered from Chinese imports, but the cheapness of these has also boosted the annual purchasing power of the average U.S. household substantially. China is also the largest export market for the U.S., with China increasing its consumption of US food products 16-fold from 2000 to 2022.[1] This relationship has helped drive investment-led growth in both countries and enabled the cash-strapped US to overcome some of the implications of its inadequate domestic savings.

Such economic decoupling would not just hurt the two protagonists but could cripple the world economy. The countries that would likely suffer the most are the lower income regions and ‘third-party’ countries (i.e., not the US and its allies, or China and allies). The World Bank (2023a) estimates that if investor confidence were to falter due to increasing trade tensions among the most powerful economies, 30 to 50 million people worldwide could slip below the poverty line by 2030.[2]

The issue of national security is also evident in the debate around food supply – previously one of globalisation’s great success stories. Security and sustainability fears are both evident here. Feeding growing populations now must be achieved against an increasingly difficult environmental backdrop. In many economies, concerns around climate change, fresh-water availability, and biodiversity are making food output less predictable and less sustainable. There has been a reduction of 60% in total global renewable water resources per capita over the last 60 years (World Bank, 2023b) and at the same time, the UN (2022) estimates that land degradation costs more than 10% of world annual GDP, threatening 52% of all agricultural land. Disruption of food supplies can threaten populations on an existential level.

Recent events (e.g. the Russia/Ukraine war) have in addition made it clear that the concentration of some sorts of agricultural production in a few producer economies may deliver short-term cost-efficiency but can increase the risks posed by events such as harvest failure or regional conflict (before the Russian/Ukraine war, the two countries combined exported nearly 12% of food calories globally). Specialisation can also lead to a higher dependence on inter-regional food trade. For example, Africa now imports around 80% of its goods from outside the region (the EU imports only 26%).

Choices here are complex and difficult. The choice is not just between more globalised and localised food production systems. We may also have to choose between systems that focus on climate change concerns, and those that address a wider range of sustainability issues. It is all too easy to identify numerous inherent tensions here, for example around food prices and different ways to calculate the cost of producing food. The delivered cost of food (the bushel on the quayside) is no longer the major issue here.

Sustainability and security concerns are also changing the trade debate in other areas, for example energy. We are conditioned to think of energy as primarily driven by international trade of the primary energy source (e.g. oil). But weaknesses around globalisation, sustainability concerns and technological advances are forcing a rethink. The transition to a more sustainable energy system will require changes to how we distribute, store and consume energy. Intermittency of renewable supply (due to lack of sun, wind or water) is already prompting a wide debate about the energy value chain. Energy will be a key component of the ‘just transition’ – the concept that moving to more sustainable economic models must be fair to all.

Within the food and energy sectors, traditional trade regimes are therefore already being complemented by other priorities. Net zero commitments and the rise of the renewables sector are already forcing changes to how we produce and how we trade in many other sectors too – with the imposition of carbon taxes an obvious example.

I argued above that economists’ concerns have often been dependent on economic circumstances. Hence, we have moved from absolute advantage through various iterations of “comparative advantage”, but always with the proviso that the trade in an individual good or service is considered in isolation (i.e. without its environmental costs). Now I think we are moving to a more holistic approach, where we are increasingly willing to impose some barriers to trade (e.g. carbon markets) in the hope of making the underlying markets work more, not less, efficiently – in the sense that they should truly reflect the long-term “cost” (environmental or otherwise) of all the inputs to the finished good or service.

There is great scope for international fall-out here. Carbon taxes, for example, will be introduced by different regions or countries at different rates – there is no multilateral consensus here. Natural capital accounting is still a very new framework, although we do now have a UN statistical framework in approach. Reconciling the trilemma of efficiency, equity and the environment will not be easy as we try to move to more sustainable economic models. But debate here at least shows that environmental and transition concerns are forcing us to think again about how to build a new global framework, rather than just accept a bilateral approach. Globalization is not dead, but it may need to reinvent itself.

Markus H.-P. Müller is Global Head of the Chief Investment Office and Chief Investment Officer ESG Private Bank, Deutsche Bank AG. Markus has held teaching posts in corporate finance and economics, being a visiting scholar at the Frankfurt School of Finance and the University of Bayreuth as well as at the Banking and Finance Academy of the Republic of Uzbekistan in Tashkent. His main research interests lie in the structural transformation of economies and societies as well as in the area of sustainability. Markus authored several books and articles on the transformation of society and economies. For his latest op-ed, please see here.

Photo by DS stories

References

- Casanova, R. (2022), ‘The CHIPS Act has already sparked $200 billion in private investments for US semiconductor production’, Semiconductor Industry Association, last updated May 23, 2023, accessed https://www.semiconductors.org/the-chips-act-has-already-sparked-200-billion-in-private-investments-for-u-s-semiconductor-production/

- Chetverikov et al (2016), ‘IV Quantile Regression for Group-level Treatments, with an Application to the Distributional Effects of Trade’ (No. 21033), NBER, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21033/w21033.pdf

- Goldberg, P. and Reed, T. (2023), ‘Is the Global Economy Deglobalizing? And if so, why? And what is next?’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, BPEA Conference Drafts, March 30-31, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/BPEA_Spring2023_Goldberg-Reed_unembargoed.pdf

- Goodrich, J., Varadarajan, R., Varas, A. and Yinug, F. (2021), ‘Strengthening the global semiconductor supply chain in an uncertain era’, Semiconductor Industry Association, accessed https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/BCG-x-SIA-Strengthening-the-Global-Semiconductor-Value-Chain-April-2021_1.pdf

- Laboure, M. and Ainsworth-Grace, C. (2023a), ‘Thematic Research: CHARTBOOK – Tangled Wires: The Geopolitical Landscape of Semiconductors & Rare Earth Metals’, Deutsche Bank Research, accessed https://research.db.com/Research/TinyUrl/GWYD9

- Laboure, M. and Ainsworth-Grace, C. (2023b), ‘Thematic Research: US-China on semiconductor chips: 10 slides on an unprecedented situation’, Deutsche Bank Research, accessed https://research.db.com/Research/TinyUrl/6P93H

- Müller, M., Laboure, M., Richardson, G. (2023), ‘The great decoupling? Rethinkable sustainable globalisation’, Deutsche Bank, accessed The great decoupling? Rethinking sustainable globalisation | Investing Themes (deutschewealth.com)

- World Bank (2023b), ‘Renewable internal freshwater resources per capita (cubic meters)’, World Bank, accessed https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.H2O.INTR.PC

- UN (2022), ‘Chronic land degradation: UN offers stark warnings and practical remedies in Global Land Outlook 2, United Nations: Convention to Combat Desertification, accessed https://www.unccd.int/news-stories/press-releases/chronic-land-degradation-un-offers-stark-warnings-and-practical

[1] Haver Analytics.