Global Politics at a Crossroads

This is a transcript of a talk given by David Held at the Federazione Nazionale dei Cavalieri del Lavoro as part of a conference on ‘The Challenge to Western Democracies: The role of Europe and Italy in present-day’s new framework of international relations’, 23rd September 2017.

Many states today claim they are democratic, yet the history of their political institutions and processes reveals the fragility and vulnerability of many democratic arrangements. The history of twentieth century Europe alone makes clear that democracy is a remarkably difficult form of government to create and sustain. And, today, we are witnessing the resurgence of authoritarianism and new threats to democracy. Why?

Democracy is built on the values of citizenship, and the equal political freedom of all citizens. The equal standing of every member of the political community is the heart beat of the democratic process. Recognition of the other is, in principle, built into the fabric of democratic societies even though clash of interests, intense political debate and daily conflict of judgement and opinion are routine. The ideal, the hope and the aspiration of democracy is to include all citizens, to ensure self-determination, to find ways of accommodation, even in the face of disagreement and political conflict.

Even in our fraught and imperfect world, the idea of the politics of compromise and accommodation—the bedrock of democratic politics —can just about survive. Political compromises are made, negotiations continue, rhetoric rises and falls with the ebb and flow of democratic politics. Barring some extreme examples, legislators from different sides of the aisle can still talk and have tea across most, if not all, democratic countries. While all ideologies regard their views as right, in the politics of accommodation, opposing views are at least considered valid.

This no longer is the case in several countries, with opponents and opposing views increasingly delegitimised and discarded, and their advocates mocked, dehumanised and even threatened. Recent examples range from Trump’s America to Brexit Britain, from Orbán’s Hungary to Modi’s India, and from Erdoğan’s Turkey to Duterte’s Philippines. When political systems become tolerant to falsehood and deceit on seismic levels, and when they even offer promotion to those who champion lies, democracy becomes vulnerable and highly fragile. And when those who oppose this are ridiculed and cast aside, the politics of accommodation begins to fracture.

The retreat to nationalism and militant identity politics is counter to the process of accommodation that has underpinned European and world peace since the end of the Second World War. It is as if all that was learnt in the wake of World War II and the Holocaust and the Gulag risks being undone. And yet, it would be false to assign all responsibility for the erosion of accommodation to right wing populist politics alone. Exclusionary politics can, and does, come from all sides of the political spectrum. The difference between the far-left and far/alt-right is that the former remains at the margins at the time of writing, while the latter has been galvanized and empowered in critical respects.

The 1930s saw the rise of xenophobia and nationalism in the context of prolonged and protracted economic strife, the lingering impact of World War I, weak international institutions and a desperate search for scapegoats. The 2010s has notable parallels: the protracted fallout of the financial crisis, ineffective regional and international institutions, and a growing xenophobic discourse that places virtually all blame for every problem on some form of Other. In the 1930s the politics of accommodation gave way to the politics of dehumanisation, war and slaughter. In the 2010s, we are taking steps down a dangerously similar path. The question remains: will knowing this help us choose a different route?

At issue is whether and to what extent the equal moral standing of each and all, and the equal liberty of all persons in the democratic process, continue to play a constitutive role in contemporary life. When the politics of accommodation is under pressure, and the patience for the protracted world of deliberation, negotiation and compromise runs out, the temptation is to look for short cuts, for political leaders who might impose their charismatic, albeit arbitrary, will. The dangers are all too obvious – a political system, increasingly impervious to opposition and challenge, and in the hands of those who will corrupt it further.

The alternative is to recover the core ideas and concepts of democratic life, mediated by the rule of law and accountable to all citizens. Between authoritarianism and a renewal of democratic life stand, of course, a set of institutions (including the division of powers, the rule of law, and bills of rights) and agents of change (among others, committed politicians, lawyers, and civil society activists) whose workings and pressures will help determine the direction of political travel in the years ahead.

Gridlock and the rise of nationalism

In order to grasp the reasons why we are at a crossroads in global politics, it is important to understand the deep drivers of political change in recent decades. One of the central concepts needed to unlock this is ‘gridlock’ and the way it threatens the hold and reach of the post-Second World War settlement and, alongside it, the principles of the democratic project and global cooperation (see Hale, Held and Young, 2013).

The post-war institutions, put in place to create a peaceful and prosperous world order, established conditions under which a multitude of actors could benefit from forming stable political institutions, developing corporations, investing abroad, creating global production chains, and engaging with a plethora of other social and economic processes associated with globalization. This is not to say that these institutions were the only cause of the dynamic form of globalization experienced over the last few decades. Nonetheless, all of these changes were allowed to thrive and develop because they took place in a relatively open, peaceful, liberal, institutionalized world order (cf. Ruggie, 1982). It was an effective design, and it worked for many decades.

These developments, however, have now progressed to the point where our ability to engage in further global cooperation has been altered. That is, the economic and political shifts in large part attributable to the successes of the post-war rule-based order are now amongst the factors grinding that system into gridlock. In areas such as nuclear proliferation, the explosion of small arms sales, terrorism, failed states, global poverty and inequality, biodiversity losses, water deficits and climate change, multilateral and transnational cooperation is now increasingly ineffective or threadbare. Gridlock is not unique to one issue domain, but appears to be becoming a general feature of global governance. Cooperation seems to be increasingly difficult and deficient at precisely the time when it is extremely urgent. Why?

There are four reasons for this blockage, or four pathways to gridlock: rising multipolarity, harder problems, institutional inertia, and institutional fragmentation. Each pathway can be thought of as a growing trend that embodies a specific mix of causal mechanisms.

First, reaching agreement in international negotiations is made more complicated by the rise of new powers like India, China and Brazil, because a more diverse array of interests have to be hammered into agreement for any global deal to be made. On the one hand, multipolarity is a positive sign of development; on the other hand, it can bring both more voices and interests to the table that are hard to weave into coherent outcomes.

Second, the problems we are facing on a global scale have grown more complex, penetrating deep into domestic policies and are often extremely difficult to resolve. Multipolarity coincides with complexity making negotiations tougher and harder.

Third, the core multilateral institutions created 70 years ago, for example, the UN Security Council, have proven difficult to change as established interests cling to outmoded decision-making rules that fail to reflect current conditions.

Fourth, in many areas international institutions have proliferated with overlapping and contradictory mandates, creating a confusing fragmentation of authority.

These trends combine in many sectors to make successful cooperation at the global level extremely difficult to achieve. The risks that follow from this are all too obvious. To manage the global economy, prevent runaway environmental destruction, reign in nuclear proliferation, or confront other global challenges, we must cooperate. But many of our tools for global policy making are breaking down or inadequate – chiefly, state-to-state negotiations over treaties and international institutions – at a time when our fate and fortunes are acutely interwoven.

Signs of this today are everywhere: climate change is still threatening all life as we know it, conflicts such as Iraq continue to run out of control, small arms sales proliferate despite all efforts to contain them, migration has increased rapidly and is destabilising many societies, and inequality threatens the fabric of social life across the world. Today it seems that gridlock also has a self-reinforcing element (see Hale and Held et al, 2017, pp. 252 - 57).

The vicious circle of self-reinforcing gridlock

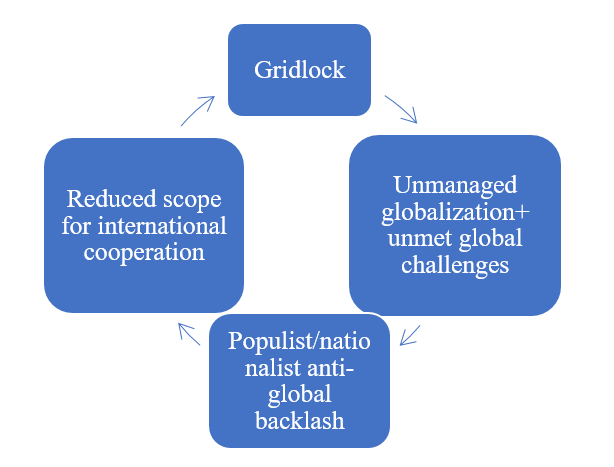

There are four stages to the process of self-reinforcing gridlock: see figure 1

Figure 1: The vicious cycle of self-reinforcing gridlock

First, we face a multilateral system, as previously noted, that is less and less able to manage global challenges, even as growing interdependence increases our need for such management.

Second, in many areas this has led to real and, in many cases, serious harm to major sectors of the global population, often creating complex and disruptive knock-on effects. Perhaps the most spectacular recent example was the 2008–9 financial crisis, which wrought havoc on the world economy in general, and on many countries in particular.

Third, these developments have been a major impetus to significant political destabilization. Rising economic inequality, a long-term trend in many economies, has been made more salient by the financial crisis, reinforcing a stark political cleavage between those who have benefited from the globalization, digitization, and automation of the economy, and those who feel left behind, including many working-class voters in industrialized countries. This division is particularly acute in spatial terms: in the cleavage between global cities and their hinterlands.

Global cities like London, Paris, Shanghai, New York, and San Francisco have become nodes of power and influence in the global economy. Their citizens have benefited directly as opportunities have sharply risen. By contrast, those in the hinterlands, typically rural areas and deindustrialized cities, have often been left behind in absolute and relative terms, building up frustrations and resentments. The effect on politics has been profound, with a number of nationalist and populist movements emerging and, in some cases, winning elections (or otherwise seizing power) in many countries.

The financial crisis is only one area where gridlock has undercut the management of global challenges, and undermined political support for global cooperation and the achievements of the post-war period. Consider the global response to terrorism. International cooperation has failed to prevent extremists from attacking civilians around the world, although it has, of course, clearly prevented many such attacks. The attacks that have taken place have been all too effective in stimulating a public discourse that sees a long-lasting war between Islamists and the West. This sentiment, in turn, can lead to political pressure for militarized responses that can create as many terrorists as they eliminate, as well as anti-Muslim policies that breed further resentment.

The failure to manage terrorism, and to bring to an end the wars in the Middle East more generally, have also had a particularly destructive impact on the global governance of migration. With millions of refugees fleeing their homelands, many recipient countries have experienced a potent political backlash from right-wing national groups and disgruntled populations, which further reduces the ability of countries to generate effective solutions to problems at the regional and global level.(And at the national level – Brexit! Or, the emergence of a more confident right wing populist party in Germany.)

We see such trends across many different kinds of countries. But the anti-global backlash is heterogeneous and rife with contradictions. It encompasses terrorism in the name of Islam, and Islamophobic discrimination against Muslims. It includes leftist rejection of trade agreements, and right-wing rejection of environmental agreements. The powerful tie that unites these disparate movements is a rejection of global interdependence and collective efforts to govern it. The resulting erosion of global cooperation is the fourth and final element of self-reinforcing gridlock, starting the whole cycle anew.

Democracy at risk

At the current conjuncture, modern democracy lies between hope and deep concern. It offers hope because it shows the way to contain despotism and tyranny through the separation of powers, the rule of law and the electoral system, and to subject political claims to tough political scrutiny through parliamentary debate, the press and social media. This hope builds on centuries of philosophical and political debate about how best to frame political communities in constitutional and democratic institutions.

Modern democracy was supported by the post-Second World War institutional breakthroughs that provided the momentum for decades of sustained economic growth and geopolitical stability, even though there were, of course, proxy wars fought out in the global South. This enabled the steady transformation of the world economy, the shift from the bipolar Cold War to a multipolar order, and the rise of global communication and networked societies.

However, what works then does not work as well now, as gridlock freezes problem-solving capacity in global politics. From the global financial crisis to new waves of migration and shifting patterns of terrorism, gridlock, alongside the fallout from the 9/11 wars, helped engender a crisis of democratic politics, as the politics of accommodation gave way to populism and authoritarianism across the world. While this remains a trend which is not yet set in stone, it is a powerful and dangerous development.

Hegel reminds us in the Element of the Philosophy of Right that ‘the owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the onset of dusk’ (1991: 23). We cannot yet know whether the democratic order will be eroded or eclipsed in the period ahead. Major leaps forward in the institutional design of nations and the world order often follow major wars and calamities. But political wisdom requires that we learn to make significant changes before tragedies unfold, and not just with hindsight.

After all, our ability to harm ourselves has increased; when weapons of mass destruction, global pandemics, and environmental collapse loom, reform-through-crisis becomes a very unattractive option. Looking back at the institutional world order set down after 1945, and the reasons for its successes and failures, it is clear that we have to understand and grasp these if we are to avoid the cycle of calamitous tragedies and institutional change.

How we shift from the postwar institutional order to a new structure of democracy and managed interdependence is a major question. But it is not a question that is easily answered.

David Held is Master of University College, Durham, and Professor of Politics and International Relations at Durham University. He is also a Director of Polity Press and General Editor of Global Policy journal.

Image Credit: David Williamson Via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

References:

Hale, T., Held, D. and Young, K. 2013. Gridlock: Why Global Cooperation Is Failing When We Need It Most. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hale, T. and Held, D., et al. 2017. Beyond Gridlock. Cambridge: Polity Press.